- En

- Fr

- عربي

ENHANCING INTERNATIONAL MILITARY COOPERATION AS A STRATEGIC TOOL FOR CAPABILITY DEVELOPMENT IN THE LEBANESE ARMED FORCES

A Framework for Sustainable Partnership and Operational Readiness

Abstract

This article explores the strategic role of international Military cooperation (IMC) in enhancing the operational and institutional capabilities of the LAF. Drawing on my experience as Director of the Directorate of IMC, the study analyzes current practices, identifies challenges, and proposes a framework for more effective and sustainable engagement with international partners.

Through a combination of policy analysis, case studies, and comparative research, the article examines how bilateral and multilateral cooperation ranging from training and joint exercises to technical assistance and defense diplomacy can serve as a catalyst for building military readiness, strengthening interoperability, and supporting institutional reform within the LAF. Particular focus is given to lessons learned from partnerships with countries such as the Unite States, UK, France, Italy and Germany as well as engagements with regional and IOs including the United Nations (UN) and NATO.

The research highlights gaps in coordination, legal frameworks, and resource planning, and offers practical recommendations to institutionalize cooperation within a comprehensive national defense strategy. Ultimately, the article advocates for a strategic shift from reactive engagement to proactive planning, where IMC is fully aligned with Lebanon’s security needs and long-term defense priorities.

Chapter One

Introduction

1.1 Executive Summary

Since the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990, IMC has been a cornerstone in the rebuilding, unification, and professionalization of the LAF. With the support of friendly nations and international partners, the LAF has gradually transformed from a fragmented force into a unified national institution capable of defending Lebanon’s sovereignty, supporting internal stability, and contributing to regional peace.

Over the past three decades, cooperation with international actors has been instrumental in addressing a wide spectrum of strategic challenges. It played a decisive role in re-establishing the chain of command and operational cohesion across all LAF units, particularly in the post-war years. It supported the LAF in confronting repeated Israeli aggressions, most notably during the 2006 war, and in enhancing border defense capabilities. Through sustained training, equipment donations, and planning support, international partners helped the LAF develop the skills and resilience necessary to wage a long-term campaign against terrorism, notably during the battles of Nahr el-Bared in 2007 and the border operations in 2014–2017.

The LAF has also benefitted from cooperation in the context of internal security missions—assisting the Internal Security Forces (ISF) and General Security in times of crisis, maintaining stability in urban centers, and responding to national emergencies. One of the most enduring and structured forms of cooperation has been the LAF’s coordination with the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), particularly in the South Litani sector (SLS), where the LAF works daily alongside international peacekeepers to monitor the cessation of hostilities, prevent escalation, and extend state authority.

As Director of the DIMC, I have had the privilege of overseeing and coordinating many of these efforts. While the achievements are significant, challenges remain chief among them the need for a more strategic, coherent, and forward-looking approach that fully integrates cooperation into national defense planning. This article examines how military cooperation has supported the LAF historically, assesses its current structure and limitations, and proposes a framework to institutionalize and strengthen it for the future. By aligning international partnerships with national priorities, the LAF can enhance its capabilities, reinforce its autonomy, and continue to serve as a pillar of national unity and stability.

1.2 Background and Context

1.2.1 The Historical Evolution of the LAF.

Since Lebanon’s independence in 1943, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) have undergone a complex transformation. The end of the civil war in 1990 marked a critical turning point, with the Taif Agreement calling for the unification of divided armed factions under central command. Rebuilding the LAF became a national and international priority, drawing support from global and regional partners. IMC played a vital role in restoring credibility, professionalism, and unity. Assistance helped rehabilitate infrastructure, equip forces, and train personnel. These partnerships enabled Lebanon to rebuild its defense institutions aligned with democratic values and international military standards.

1.2.2 Military Cooperation in Response to Strategic Threats.

From the 1990s to the early 2000s, Lebanon’s security environment was marked by instability, including persistent Israeli Enemy Forces (IEF) threats, foreign armed groups, and internal political tensions. The IEF occupation of southern Lebanon until 2000, followed by the 2006 war, challenged national sovereignty. During these times, International Military Cooperation (IMC) was vital in enhancing LAF operational readiness and defense capabilities. After 2006, UN Security Council Resolution 1701 fostered deeper cooperation between the LAF and UNIFIL in the Southern Litani Sector (SLS). This partnership remains a key example of structured international collaboration, involving joint patrols, coordination, and efforts to reinforce state authority.

1.2.3 The Syrian Border Challenge and the Fight against Terrorism

The 2011 Syrian conflict added urgency to Lebanon’s security challenges, as instability along the eastern and northern borders enabled terrorist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS to infiltrate, clash with the LAF, and attack civilians in towns such as Arsal and Qaa. These threats demanded a strategic shift toward border security and counterterrorism. IMC was crucial: the United States and United Kingdom provided equipment and surveillance under the Land Border Security Program; France and others offered specialized training. Enhanced intelligence sharing supported operations. The 2017 Fajr al-Joroud campaign cleared the northeast of terrorists an achievement made possible by sustained international support.

1.2.4 Internal Security Missions and National Resilience

Beyond external threats, the LAF has played a critical role in maintaining internal stability. It has responded to armed clashes, civil unrest, disasters, and supported agencies like the ISF and General Security. These responsibilities have grown in frequency and complexity, especially during political paralysis, social unrest, and national emergencies such as the Beirut port explosion. In this context, IMC has been essential, enhancing the LAF’s ability to respond through training in urban operations, crisis management, and civil-military coordination. Partners also provided key equipment for mobility, communications, and crowd control, enabling the LAF to act swiftly and effectively in crises.

1.2.5 The Gaza War of 2023 and the Impact on Lebanon

The 2023 Gaza War further intensified Lebanon’s security challenges as the conflict between Israeli Enemy Forces (IEF) and Hamas spilled into the region. Clashes along Lebanon’s southern border, especially between Hezbollah and the IEF, escalated tensions and threatened national stability. Lebanon’s leadership called for greater coordination with international partners, particularly UNIFIL, to contain the crisis and prevent wider conflict. For the LAF, the situation demanded heightened readiness against infiltration, cross-border attacks, and internal unrest. Support from France, the Unite States, and European allies through intelligence sharing and resource provision enabled the LAF to uphold neutrality, protect sovereignty, and avoid escalation into full-scale war.

1.2.6 The War in Lebanon 2024: A New Challenge

The 2024 war in Lebanon marks a deeply troubling turn in the country’s security landscape, triggering widespread regional instability. Though details continue to unfold, the conflict involves complex internal and external actors, including heightened Hezbollah activity and growing extremist threats. These dynamics have pushed the LAF to carefully balance national stability with the risk of wider confrontation. IMC remains essential, enabling the LAF to secure borders, protect civilians, and stabilize internal security. Support from international allies in intelligence, operations, and humanitarian aid has been vital. This crisis underscores the enduring value of sustained cooperation in preserving Lebanon’s sovereignty.

1.2.7 Institutionalizing Cooperation: The Role of the DIMC

Recognizing the need for a more strategic approach to foreign partnerships, the LAF established the DIMC as the central body for managing external defense relations. It coordinates with defense attachés, military advisors, and IOs to align support with the LAF’s strategic priorities. The DIMC oversees bilateral technical arrangements, defense dialogues, multilateral initiatives, and strategic planning. Despite its expanded role, challenges persist, including overlapping efforts, limited strategic guidance, legal constraints, and weak coordination with internal stakeholders. To address these, cooperation must be more institutionalized and fully integrated into national defense planning, rather than operating in parallel.

1.3 Purpose of the Study

This article seeks to analyze how IMC has contributed to the development of the LAF since 1990, with a particular focus on operational readiness, counterterrorism, border defense, and institutional reform. It assesses the current structure, identifies gaps, and proposes a framework to make cooperation more strategic, sustainable, and aligned with Lebanon’s evolving security needs. By doing so, it aims to support the LAF’s vision of becoming a more capable, autonomous, and resilient force one that is rooted in national values but open to global engagement.

1.4 Scope

This article explores the strategic role of IMC in strengthening the operational readiness and institutional capacity of the LAF from 1990 to 2025. It examines how partnerships with friendly nations and IOs have supported efforts in counterterrorism, border security, and internal stability. The study analyzes bilateral and multilateral cooperation, with case studies involving the US, UK, France, and the UN, and assesses the evolving role of the DIMC. While recognizing progress, it identifies gaps in coordination and planning. The article proposes a structured framework to institutionalize IMC within Lebanon’s broader defense strategy.

1.5 Limitations of the Study

This study faces limitations due to restricted access to official data and classified materials, which constrains analysis of specific operations and strategic decisions. It relies mainly on open sources, institutional reports, and personal experience, which may introduce bias. The fluid security situation in Lebanon and shifting geopolitical dynamics could impact the relevance of some findings over time. The research focuses on formal military cooperation, excluding informal or covert partnerships. It is centered on the (LAF), without detailed evaluation of other security agencies. Time constraints and limited access to partner country assessments also narrow the scope of analysis.

Chapter Two

Literature Review

2.1 Theories and models of IMC

2.1.1 Realism and Strategic Interest

Realist theory sees Lebanon’s military cooperation with The Unite States, France, and the UK as interest-driven alliances to enhance deterrence and counter threats1. Walt’s Balance of Threat Model explains these partnerships as responses to perceived dangers, particularly from extremist groups and regional instability2 .

2.1.2 Liberalism and Institutional Cooperation

Liberal theory sees Lebanon’s cooperation with UNIFIL as promoting peace through institutions, shared norms, and dialogue. Under UNSCR 1701, multilateral coordination fosters transparency and trust. However, institutions reduce uncertainty and enhance cooperation evident in Lebanon’s structured engagement with international peacekeeping frameworks3.

2.1.3 Constructivism and Normative Engagement

Constructivism emphasizes how identity and norms shape state behavior. Lebanon’s military cooperation with NATO, The Unite States, and Europe aids norm diffusion, fostering civilian control, gender inclusion, and human rights. Repeated exposure to global norms4 and transforms military culture and strategy5.

2.1.4 Security Community and Regional Cooperation Models

A Security Community, as defined by Deutsch, emerges when states trust each other and reject force to resolve disputes. While the Middle East lacks a full model, UNIFIL’s role in Lebanon and regional forums like the 5+5 Defense Initiative reflect emerging cooperation, despite Lebanon’s limited political involvement6.

2.1.5 Network-Centric Cooperation Models

Emerging military models emphasize network-centric cooperation, where states, institutions, and non-state actors collaborate in a web of bilateral and multilateral arrangements. Lebanon’s DIMC reflects this approach, coordinating with diverse defense partners under various legal and operational frameworks. Network Governance in Security highlights this decentralized, adaptive model7 .

2.1.6 Comprehensive Approach and Whole-of-Government Models

Modern security cooperation increasingly adopts a comprehensive approach, integrating defense with diplomatic, development, and humanitarian efforts. In Lebanon, military assistance is often paired with support for civil-military coordination, governance, border management, and institutional reform, particularly through EU and UNDP programs. This reflects broader trends in integrated security frameworks, emphasizing cross-sectorial coordination8.

2.2 Comparative Analysis of Military Diplomacy in Small and Middle-Power States

Military diplomacy has become an increasingly vital tool for small and middle-power states seeking to enhance their strategic relevance, build defense capabilities, and navigate complex regional and global security environments. While traditionally associated with major powers, the practice of military diplomacy among smaller states demonstrates innovative approaches tailored to their specific national interests, resource constraints, and geopolitical contexts9.

2.2.1 Jordan has long leveraged military diplomacy to secure international support and position itself as a stable and reliable partner in a volatile region. Through extensive bilateral and multilateral engagements, notably with the US, United Kingdom, NATO, and Arab partners, Jordan has received substantial military assistance, training, and equipment10. The Jordanian Armed Forces' participation in peacekeeping missions, joint exercises, and counterterrorism initiatives has not only enhanced operational capabilities but also bolstered Jordan’s diplomatic standing. Crucially, Jordan’s military diplomacy is deeply aligned with its internal stability strategy and its efforts to project itself as a moderate, reform-oriented actor in the Middle East11 .

2.2.2 The United Arab Emirates (UAE) offers a different but equally instructive model. With substantial financial resources, the UAE has pursued an ambitious military diplomacy agenda aimed at modernizing its armed forces and projecting power beyond its borders. Strategic partnerships with The Unite States, France, and others have enabled the UAE to acquire advanced technologies, develop professional military educationprogrammers, and participate in international coalitions, including operations in Afghanistan and Yemen12. The UAE's military diplomacy is closely tied to its broader strategy of economic diversification, international branding, and regional influence.

2.2.3 Georgia, a small state situated at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, exemplifies military diplomacy driven by security vulnerability and aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration. Following conflicts with Russia, Georgia has prioritized military cooperation with NATO, the US, and the European Union (EU), focusing on defense reform, interoperability, and capacity-building13. Participation in NATO missions and bilateral defense cooperation initiatives has significantly strengthened the Georgian Armed Forces' professionalism, resilience, and alignment with Western military standards14.

Across these cases, several common themes emerge: the strategic use of military diplomacy to compensate for limited conventional power; the importance of aligning defense cooperation with broader political and economic strategies; and the necessity of building institutional frameworks that sustain long-term partnerships.

2.3 The Role of Security Assistance, Joint Training, and Interoperability

Security assistance, joint training, and interoperability are central pillars of modern IMC, especially for small and middle-power states seeking to enhance their defense capabilities, professional standards, and strategic resilience.

2.3.1 Security Assistance

It encompasses a broad range of activities, including the provision of equipment, financial support, training programmers, advisory missions, and infrastructure development. For the LAF, security assistance has been essential to overcoming resource constraints and capability gaps. Bilateral security assistance from key partners particularly the US, France, the UK, and Italy—has enabled the LAF to acquire critical capabilities such as mobility, communications, surveillance, and counterterrorism skills15. Moreover, assistance programmers often integrate elements of institutional reform, focusing on logistics, planning, human resources, and military justice systems, thus fostering long-term self-sufficiency.

2.3.2 Joint Training

It plays a pivotal role in developing operational skills, enhancing tactical proficiency, and building mutual trust between partner forces. Training exercises allow the LAF to familiarize itself with different doctrines, operational techniques, and equipment, while also preparing for complex missions such as urban warfare, border security, peacekeeping operations, and disaster response. Regular joint exercises with international partners also promote the exchange of best practices, the strengthening of professional norms, and the reinforcement of civilian oversight mechanisms within the military.

2.3.3 Interoperability

It is the ability of military forces from different countries to operate together effectively is a strategic objective of international cooperation. Interoperability requires standardized procedures, compatible communication systems, shared operational concepts, and a mutual understanding of each other’s tactics and rules of engagement16. For Lebanon, achieving higher levels of interoperability with international forces, particularly UNIFIL, NATO members, and Arab partners, enhances operational effectiveness in peacekeeping missions, border management, counterterrorism operations, and humanitarian responses. Furthermore, it increases the LAF’s ability to participate meaningfully in multinational exercises and potential future peace support operations beyond national borders.

Chapter Three

Current State of IMC in the LAF

3.1 Institutional Structure of the DIMC

The DIMC is a core part of the LAF structure, operating under Army Command to manage relations with foreign military partners. It coordinates international cooperation, support programs, and strategic engagements. By aligning external military interactions with national defense priorities, the DIMC contributes to the LAF’s development, modernization, and capacity building. The next sections will outline the overall LAF structure, followed by a detailed look at the DIMC’s roles and internal organization.

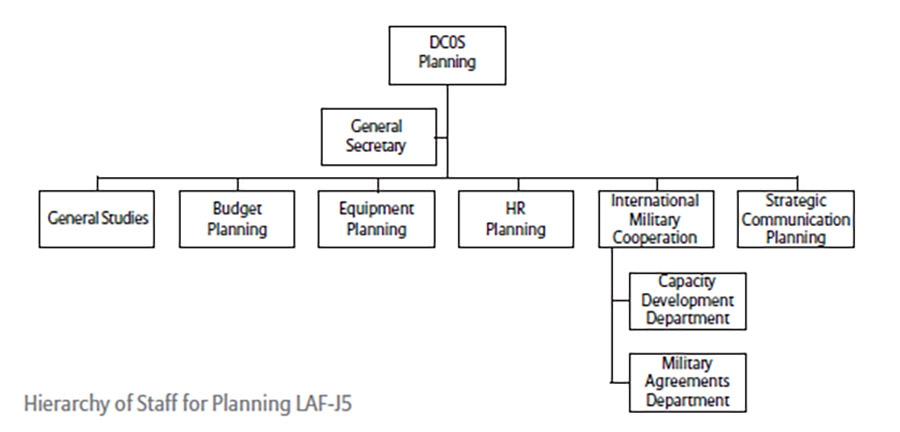

3.1.1 The Mission and Structure of the Staff for Planning J5:

The LAF J5 is responsible for representing a long and medium-term military policy for the forces according to the directives of the CINC. This includes developing doctrine, organization, equipment, size, and costs, as well as determining targets that are compatible with the defense tasks decided by the Supreme Defense Council. The LAF- J5 is also responsible for converting the above goals into plans and approaches, defining many policies, and realizing the LAF's needs in terms of equipment. The LAF- J5 is linked with several directorates, including Directorate of General Studies, Budget Planning, and Planning for HR, Planning for Equipment, IMC, and the Directorate of Planning for Strategic Communication.

3.1.2 The Mission and Structure of the DIMC

The DIMC manages the LAF’s relations with foreign militaries. It coordinates joint activities, treaties, and international agreements. It also supports strengthening the LAF through foreign assistance and it consists of:

3.1.3 The Department of Capability Development

The Capability Development Department identifies operational needs, plans long- and medium-term capability growth, and manages modernization projects across all domains. It also coordinates with national and international partners to secure resources and support17.

3.1.4 The Department of Military Agreements

To fulfill its capability development role, the DIMC’s Department of Military Agreements must maintain active engagement with international partners. This ensures access to vital resources, effective negotiation of support agreements, and alignment of Lebanon’s defense priorities with partner interests. Continuous communication also fosters trust and long-term cooperation18.

3.2 Mapping Current Bilateral/Multilateral Engagements (US, UK, France, etc.)

In recent years, the LAF have received significant military cooperation and assistance from various countries and IOs. These include training opportunities abroad, equipment, and capacity-building efforts from nations like the US, UK, France, Egypt, India, and the UAE, among others. This support has played a crucial role in enhancing the LAF’s capabilities. The following sections summarize the key military cooperation programs provided to the LAF between 2018 and 2024.

3.2.1 The United States provided over $585M in FMF and $322.8M in BPC to the LAF, enabling major upgrades across land, air, and naval domains. Notable programs include IMET (846 personnel), CAS training, CBRN, and surveillance improvements through DTRA and USACE projects19.

3.2.2 United Kingdom provided $35M in donations; the UK has led NSAP and British Training and Advisory Team (BTAT) initiatives, supporting border regiments, Puma/Gazelle maintenance, naval boarding teams, and leadership training. It also contributed to STRATCOM and gender programs20.

3.2.3 France provided $28M in aid, trained 124 officers, and supported PSYOP, anti-tank, and mountain warfare capacities21. It helped establish the JRCC and JOIC, and donated RHIBs, fuel, and simulation tools22.

3.2.4 Germany supported CBRN, military police, and EOD capabilities, including border surveillance equipment and training23. It also contributed to LAF logistics reforms24. Italy supported the LAF Navy through training, RHIB donations, and UNIFIL maritime coordination25 and it also trained personnel in humanitarian demining26.

3.2.5 Canada provided institutional development support in governance reform, training, and engineering, under the Military Training and Cooperation Program (MTCP)27.

3.2.6 Netherlands focused on EOD, border security, and demining training, offering both in-country and overseas capacity-building programs28.

3.2.7 EU through CSDP and EULEB cooperation, supported civil-military border control, CBRN, and maritime security under trust funds and multilateral platforms29.

3.3 Assessment of Existing Frameworks, Successes, and Gaps

The DIMC is key to military diplomacy and international coordination. This assessment examines its frameworks, successes, and challenges, offering insights to strengthen institutional effectiveness and align future cooperation efforts with Lebanon’s strategic defense priorities.

3.3.1 Existing Frameworks.

(1) Policy and Structural Frameworks.

DIMC operates under the LAF-J5, with a mandate to manage military diplomacy, bilateral and multilateral cooperation, and international engagements30.

(2) Legal and Strategic Instruments: DIMC works through:

a) Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs)

b) Technical Arrangements (TAs)

c) Crisis Notes and diplomatic correspondence

(3) Educational and Institutional Engagement.

a) Engagements with international military education institutions and partner-led initiatives (e.g., Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, US Army War College).

b) Integration of international norms and NATO-compatible processes where feasible31.

3.3.2 Successes.

(1) Strategic Visibility and Credibility

a) LAF has developed a reputation as a reliable partner, leveraging DIMC to maintain balanced relationships with multiple actors (e.g., UK, US, France, UNIFIL)32.

b) Published academic work and participation in forums enhance LAF’s intellectual presence33.

(2) Operational Cooperation

a) Successful coordination of joint exercises34.

b) Enhanced interoperability and understanding of foreign partner systems.

(3) Institutional Planning

• The 2023–2027 CDP aligned partner support with national priorities35.

3.3.3 Gaps and Challenges

(1) Legal and Sovereignty Issues

a) Concerns remain over lack of reciprocal legal protections and unclear status for foreign forces during joint operations36.

b) DIMC often has to advocate late in the process for sovereignty clauses in partner-drafted agreements.

(2) Mission Scope and Operational Integration

a) Unclear alignment between partner military presence/support and LAF’s long-term mission scope.

b) Risk of fragmented partner support with overlapping or uncoordinated priorities37.

(3) Human and Institutional Capacity

a) Limited staffing, linguistic skills, and training in international military law and diplomacy constrain scalability.

b) Absence of a standing doctrine for military diplomacy or foreign military engagement within LAF38.

(4) Monitoring and Evaluation

a) KPIs and impact assessments for international cooperation efforts are often informal or reactive39.

b) Inconsistent documentation and knowledge transfer during rotations or leadership changes.

3.4 Partner Perceptions: Survey-Based Evaluation of DIMC Performance

3.4.1 Introduction.

To assess its coordination with international defense partners, the DIMC conducted a structured survey using standardized online forms. The questionnaire captured partner views on communication, responsiveness, alignment with objectives, and overall cooperation effectiveness. Thematic responses provided measurable insights into DIMC’s performance, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement.

3.4.2 Analysis of Survey Results.

The findings of the DIMC survey indicate a positive perception of the directorate’s performance in communication and cooperation. All respondents rated communication as “very clear,” with full trust in DIMC’s ability to represent their country’s interests. Additionally, seventy-five percent confirmed that responses to inquiries were “always timely” and “always responsive,” highlighting DIMC’s reliability as a contact point for partner nations.

While most respondents felt efforts were “mostly aligned” with mutual strategic interests, only twenty-five percent believed they were “fully aligned,” suggesting a need for deeper strategic dialogue. Support was rated highly, but there are opportunities for more tailored engagement. Key areas for improvement included communication (fifty percent), operational coordination (twenty-five percent), and procedural clarity (twenty-five percent).

The unanimous agreement that DIMC is “very open” to feedback offers a strong foundation for continuous improvement. Respondents favored email for communication, with in-person meetings also valued. However, Seventy-five percent expressed interest in launching new initiatives and bilateral meetings soon.

Chapter Four

Challenges and Opportunities

4.1 Strategic, Political, Logistical, and Legal Constraints

IMC in the Lebanese context is shaped by a unique set of constraints that reflect the country’s legal framework, political landscape, infrastructure limitations, and strategic positioning.

4.1.1 Political Constraints.

Lebanon’s confessional power-sharing system often leads to institutional paralysis, especially on issues like defense agreements and security partnerships. Political factions have differing preferences, with some favoring Western ties and others aligning with regional powers like Iran or Syria. This division complicates the creation of a unified defense policy and delays military agreements. For example, defense cooperation frameworks with NATO or the EU have faced resistance due to concerns over sovereignty and neutrality40. Consequently, the LAF operates in a fragmented political environment, hindering its ability to plan and sustain long-term IMC.

4.1.2 Logistical Constraints

Lebanon’s military logistics system faces major challenges due to underinvestment and infrastructure limitations, including limited airlift and sealift capabilities, inadequate warehousing, and poor secure communication networks. While international support, such as The Unite States logistics hubs and UK-funded surveillance towers, has mitigated some gaps, the LAF remains reliant on external assistance. Large-scale joint exercises and prolonged deployments often stretch available logistics. The 2020 Beirut port explosion further disrupted vital supply chains, affecting military mobility. Despite donor-funded rehabilitation efforts, logistical issues persist, hindering the LAF’s operational readiness, emergency response, and ability to independently host multinational training and engagements.

4.1.3 Strategic Constraints

Lebanon’s geographic and regional context requires a cautious defense strategy. Positioned between Occupied Palestine and Syria, Lebanon must balance strong international relationships for legitimacy without entangling alliances. The LAF cooperates with NATO and the Arab League in a non-aligned manner to maximize benefits without binding obligations. However, strategic asymmetries persist, as partner priorities often differ from Lebanon’s defense needs, leading to donor-driven agendas. To maintain strategic autonomy, Lebanon must recalibrate engagements continuously, ensuring that foreign assistance supports, rather than substitutes, its national defense goals41.

4.1.4 Legal Constraints

Lebanon has taken a deliberate approach to IMC by formalizing partnerships through Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs), Technical Arrangements (TAs), and operational protocols. While these tools provide structure, they often lack the comprehensive legal clarity of Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs), especially concerning jurisdiction, immunity, and rules of engagement. Exercises like PEGASUS CEDAR and UK-supported training are governed by ad hoc agreements42. Although this reflects Lebanon’s intent to preserve legal sovereignty, the absence of standardized legal frameworks can hinder long-term planning, complicate deployment logistics, and reduce the effectiveness of sustained defense cooperation.

4.2 Case Studies of Effective Cooperation (BTAT, CTAT, MTC4L, UNIFIL partnerships)

4.2.1 British Training and Advisory Team Partnership

The BTAT plays a crucial role in supporting the LAF, particularly in enhancing the operational readiness of the Land Border Regiments (LBRs). Through a bilateral defense partnership, BTAT offers tailored training, strategic advisory support, and mentorship in infantry tactics, border security, civil-military operations, and NCO development. The cooperation is governed by TAs and coordinated through the LAF’s DoT and Directorate of Operations, ensuring alignment with Lebanon’s sovereignty and priorities43. BTAT has contributed significantly to the professionalization of frontline units and the broader institutional development within the LAF44.

4.2.2 CTAT Partnership

The Canadian Training Assistance Team Lebanon (CTAT-L) provides sustained institutional and tactical training support to the LAF under Canada’s broader military engagement in the region. Operating primarily under Operation IMPACT, CTAT-L collaborates with LAF training institutions to enhance leadership development, instructional capacity, and combat readiness. Key focus areas include junior officer education, civil-military cooperation, and counter-insurgency fundamentals. The partnership is coordinated with the LAF’s–DoT and reflects shared priorities on sovereignty, professionalism, and resilience. CTAT-L’s long-term presence has strengthened Lebanon’s defense education ecosystem and improved the LAF’s ability to independently design and deliver training programs45.

4.2.3 MTC4L Partnership

The Military Technical Committee for Lebanon (MTC4L) is a multilateral coordination platform that supports the LAF in strengthening its capabilities and implementing UNSCR 1701. It brings together defense representatives from the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, and other key partners to align military assistance with Lebanon’s strategic priorities. MTC4L facilitates equipment delivery, training support, and infrastructure development while promoting interoperability and institutional resilience46. The committee plays a vital role in reinforcing the LAF’s operational presence in southern Lebanon in coordination with UNIFIL, helping safeguard Lebanese sovereignty and contribute to regional stability47.

4.2.4 UNIFIL Partnership

UNIFIL has been a key part of Lebanon’s security framework since its 1978 deployment to ensure peace along the Lebanon-Occupied Palestine border. It has played a vital role in implementing UN Security Council Resolution 1701, calling for a cessation of hostilities between IEF and Hezbollah, and disarming non-state armed groups. Over the years, UNIFIL has provided the LAF with capacity-building programs, joint exercises, and technical support, helping improve Lebanon's border security. The partnership has enabled the LAF to gradually assume security responsibilities, especially since 2006, while addressing asymmetric warfare and border security concerns. Despite challenges, UNIFIL remains a cornerstone in Lebanon's security strategy48.

4.3 Risks of Dependency vs. Strategic Autonomy

4.3.1 The Strategic Trade-Off: Cooperation vs. Sovereignty

International defense cooperation is crucial for enhancing Lebanon's military capabilities but poses risks of dependency. While foreign support in training, equipment, and operations boosts short-term readiness, it can limit Lebanon’s strategic autonomy, particularly when tied to external political or operational alignment. Achieving strategic autonomy requires strengthening indigenous defense capabilities, diversifying partnerships, and having a clear national security vision. Balancing foreign cooperation with independent decision-making is vital to Lebanon’s defense policy.

4.3.2 Capability Gaps and Mismatched Assistance

Despite years of cooperation, the LAF has not consistently received the necessary support to fully meet operational needs. Much of the aid, especially in equipment, consists of outdated or second-hand systems, often based on donor surplus rather than Lebanon’s specific requirements. This has resulted in gaps, particularly in air defense, maritime surveillance, and armored mobility. While training and development have been beneficial, the lack of timely, mission-specific equipment limits the LAF’s ability to conduct independent operations and address evolving threats, reinforcing a sense of external dependency rather than fostering autonomy.

4.3.3 Toward Sustainable Strategic Autonomy

The long-term sustainability of Lebanon’s defense posture is uncertain due to reliance on legacy systems and limited technological progress, which could leave the LAF at a disadvantage compared to regional actors. Dependence on foreign logistics and interoperability reduces flexibility in independent missions. To achieve strategic autonomy, Lebanon must focus on building self-sufficient defense capabilities, advocate for need-based assistance, and develop a national armaments strategy aligned with its security needs. Addressing these imbalances in cooperation frameworks will help the LAF shift from a recipient model to a more collaborative, long-term partnership.

Chapter Five

Strategic Framework for Enhancing Military Cooperation

5.1 Policy proposals

To ensure effective and sustainable IMC, Lebanon must adopt a structured policy framework grounded in the principles of sovereignty, strategic alignment, and institutional accountability. The policy proposals below are formulated at the national strategic level, but their implementation spans both the strategic and operational levels, requiring coordinated action across ministries and military institutions.

a) Governance: A National Military Cooperation Council (NMCC), chaired by the LAF and supported by the MoD and MoFA, is proposed to ensure inter-agency coordination and policy coherence. It will approve new partnerships, ensure alignment with Lebanon’s defense strategy, and oversee compliance with legal frameworks enhancing strategic autonomy and international collaboration.

b) Metrics: A centralized Monitoring and Evaluation Unit within DIMC will use performance indicators focusing on effectiveness, partner satisfaction, and sustainability to assess cooperation. Annual reports and partner feedback will ensure transparency and continuous improvement.

c) Planning Cycles: Military cooperation will be embedded in the LAF’s five-year defense plan and guided by an annual Military Cooperation Action Plan (MCAP), ensuring adaptability to threats and alignment with strategic priorities.

d) Resource Allocation: A dedicated Military Cooperation Fund and joint financing agreements with partners will ensure sufficient funding, aligned with strategic needs while safeguarding fiscal responsibility.

5.2 Organizational Capacity Building

To shift from relying on external aid to building strong partnerships, the LAF needs to strengthen its internal capabilities. This involves investing in key areas such as the development of Defense Attachés, harmonizing military doctrines, enhancing education and language skills, and creating officer exchange programs. These improvements will ensure that the LAF can effectively manage and sustain international cooperation. These core areas of investment are:

a) Defense Attaché Role Expansion: Train Lebanese DAs in defense diplomacy, international law, and strategic communication to better represent LAF interests and enhance coordination abroad.

b) Doctrine Harmonization: Establish a Joint Doctrine Cell under J5, supported by foreign experts, to align operational concepts and terminology with key partners.

c) Military Education: Integrate modules on defense diplomacy, multinational operations, international humanitarian law, and strategic communication into military academy and staff college curricula.

d) Language Skills: Prioritize English, French, and Italian proficiency; establish language labs and offer certification incentives for international liaison personnel.

e) Rotation and Exchange Programs: Launch officer exchange programs with partner militaries and international organizations to embed LAF officers in multinational training and planning environments.

5.3 Proposal for an (IMCS) Aligned with LAF’s Long-Term Plans

To unify and guide all military cooperation efforts, this chapter proposes the development of an Integrated Military Cooperation Strategy (IMCS), anchored where available in Lebanon’s NDS. In the absence of such a strategy, the IMCS should draw its foundation from the core principles outlined in the inaugural address of the President of the Republic, the ministerial statement of the government, the provisions of the and the Defense Law. The LAF, in coordination with the MoD and the MoFA, will be responsible for developing the IMCS, ensuring it is aligned with Lebanon’s broader defense strategy and national interests.

The IMCS should include:

a) Strategic Objectives: Enhance LAF independence, ensure support aligns with actual needs, and contribute to regional security. Emphasize internal capacity-building and aligning cooperation with Lebanon’s defense priorities to reduce external reliance.

b) Priority Areas: Focus on counter-terrorism, border security, cyber defense, logistics, and coordination with partners. Additional areas include civil-military cooperation, disaster response, maritime security, and use of technologies like drones and secure communications.

c) Partnership Frameworks: Define cooperation levels (strategic, operational, and technical) and types (training, capability-building, strategic dialogue). Conduct regular reviews to improve coordination and avoid duplication.

d) Legal Architecture: Use standard agreements MoUs, TAs, and SOFAs to ensure consistency. Include pre-drafted templates for emergencies to avoid delays.

e) Risk Management: Implement tools to monitor risks to sovereignty and legal autonomy. Set limits on risk tolerance and conduct regular evaluations to prevent overdependence.

f) Coordination Mechanisms: Establish permanent bodies like the NMCC and inter-agency teams to manage cooperation and align it with national defense policies.

g) Monitoring and Evaluation: Create a system with indicators and annual reviews to assess impact, improve planning, and ensure transparency.

The IMCS could be reviewed every three years in consultation with key stakeholders and partners. Its implementation could be overseen by the NMCC and supported by DIMC, ensuring institutional ownership and operational relevance.

Chapter Six

Summary of findings and Recommendations

6.1 Summary of Findings: Strengthening Lebanon’s Military Cooperation.

To ensure the effectiveness of IMC, Lebanon must adopt a structured policy framework that aligns with its national sovereignty, strategic objectives, and institutional accountability. A central element of this framework is the establishment of a NMCC, chaired by the LAF and supported by the MoD and MoFA. The NMCC would oversee the approval of new defense partnerships and coordinate inter-agency efforts to maintain policy coherence.

A centralized Monitoring and Evaluation Unit under DIMC will monitor performance through key indicators, ensuring operational effectiveness and long-term sustainability. This unit will provide annual assessments to guide ongoing improvements in military cooperation efforts. The integration of military cooperation within Lebanon’s five-year defense planning cycle, complemented by an annual MCAP will keep initiatives aligned with evolving strategic priorities.

To support these plans, resource allocation will be key. A dedicated Military Cooperation Fund, along with joint financing agreements with international partners, will provide the necessary financial and human resources. The LAF must also enhance internal capabilities, shifting from dependency on external support to building reciprocal partnerships. This includes strengthening the role of Defense Attachés, harmonizing military doctrines, modernizing military education, and improving language proficiency to support international engagements.

The development of an IMCS will unify these efforts, identifying key priority areas such as counterterrorism, border protection, and cyber security. The IMCS will establish structured partnership frameworks, legal instruments, risk management processes, and institutional coordination to safeguard Lebanon’s sovereignty while fostering effective international partnerships.

6.2 Recommendations

To successfully implement Lebanon’s IMCS and build a strong, self-reliant defense system, the following recommendations are proposed starting from the highest national authorities and moving downward:

1. To the Lebanese Government:

a) Approve the establishment of a NMCC to coordinate all international military engagements.

b) Endorse a 10-year Strategic Roadmap for military cooperation and ensure it is upheld across successive governments.

c) Secure the legal and budgetary frameworks required to support long-term defense partnerships.

2. To the Ministry of Defense:

a) Institutionalize the NMCC and ensure it is empowered to oversee all IMC efforts.

b) Align military cooperation with national defense planning cycles and the broader strategic vision.

c) Support the LAF with policy, legal, and coordination tools needed for efficient implementation of the IMCS.

3. To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA):

a) Integrate defense diplomacy into broader foreign policy objectives.

b) Strengthen the role of defense attachés and ensure embassies support LAF’s engagement with host countries.

c) Safeguard Lebanon’s legal rights and sovereignty in all international military agreements.

4. To the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF):

a) Lead the operationalization of the IMCS with transparency, discipline, and a focus on strategic outcomes.

b) Develop internal mechanisms for monitoring, evaluation, and reporting on cooperation results.

c) Prioritize capacity-building in areas such as legal negotiations, liaison work, language skills, and doctrine harmonization.

5. To International Partners and Donors:

a) Respect Lebanon’s strategic direction and support the shift from aid dependency to long-term, balanced partnerships.

b) Align assistance with Lebanon’s defense priorities and coordinate with the NMCC to avoid redundancy.

c) Offer technical and legal support to strengthen Lebanon’s institutional capacity for managing cooperation.

6.3 Conclusions

This article showed that Lebanon needs a clear and organized approach to international military cooperation. By following principles like sovereignty, coordination, and accountability, Lebanon can move from relying on outside help to building real partnerships. The proposed IMCS gives a roadmap to guide these efforts. It includes better planning, stronger laws, regular reviews, and smarter use of resources. By improving how the LAF works with others and building its own skills and systems, Lebanon can protect its national interests, become more independent, and play a stronger role in regional and global security.

List of Abbreviations

BPC Building Partner Capacity

BTAT British Training and Advisory Team

CAS Close Air Support

CBRN Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear

CDP Capabilities Development Plan

CINC Commander in Chief

COS Chief of Staff

CSDP Common Security and Defense Policy (EU)

CTAT-L Canadian Training Assistance Team – Lebanon

DCOS Deputy Chief of Staff

DIMC Directorate of International Military Cooperation

DSCA Defense Security Cooperation Agency (US)

DTRA Defense Threat Reduction Agency (US)

EEAS European External Action Service

EOD Explosive Ordnance Disposal

ETEE Education, Training, Exercises and Evaluation

EU European Union

EULEB European Union–Lebanon Security Cooperation

FMF Foreign Military Financing

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (Germany)

IEF Israeli Armed Forces

IMC International Military Cooperation

IMCS Integrated Military Cooperation Strategy

IMET International Military Education and Training

IO International Organization

IT Information Technology

J5 Staff for Planning (LAF)

JOIC Joint Operations and Intelligence Center

JRCC Joint Rescue Coordination Center

KPI Key Performance Indicator

LAF Lebanese Armed Forces

LoT Directorate of Training

MoD Ministry of Defense

MoFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MoU Memorandum of Understanding

MCAP Military Cooperation Action Plan

MTCP Military Training and Cooperation Program (Canada)

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NCO Non-Commissioned Officer

NDS National Defense Strategy

NMCC National Military Cooperation Council

NSAP National Security Assistance Programme (UK)

PSYOP Psychological Operations

RHIB Rigid-Hulled Inflatable Boat

SME Subject Matter Expert

STRATCOM Strategic Communication

TA Technical Arrangement

UAE United Arab Emirates

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNIFIL United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon

UNSCR United Nations Security Council Resolution

US United States

USACE United States Army Corps of Engineers

References

1- Alhassan, I. (2024). Strategic realities & challenges in the armed forces: A comparative analysis between the Lebanese, US, & UK armed forces. Lebanese National Defense Journal, (126).

2- Areshidze, I. (2020). Georgia's strategic path to NATO: Challenges & prospects. Caucasus Policy Review, 5(2), 24–40.

3- Avant, D. D., & Westerwinter, C. (Eds.). (2016). The new power politics: Networks & transnational security governance. Oxford University Press.

4- Barakat, S., & Milton, S. (2020). The role of Jordanian military diplomacy in regional stability. Journal of Defense Studies, 14(1), 57–78.

5- Bensahel, N. (2006). Building security forces & security institutions. RAND Corporation.

6- British Embassy Beirut. (2021). Press release: UK support to the LAF. https://www.gov.uk/government/world/lebanon/news

7- Canadian Armed Forces. (2023). Operation IMPACT – Lebanon: Mission update.

8- Global Affairs Canada. (2022). Military Training & Cooperation Program (MTCP). https://www.international.gc.ca/

9- Cottey, A., & Forster, A. (2004). Reshaping defense diplomacy: New roles for military cooperation & assistance. Oxford University Press.

10- Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA). (2022). Lebanon: Foreign Military Financing (FMF) & Building Partner Capacity (BPC) programs. https://www.dsca.mil/

11- Deutsch, K. W., et al. (1957). Political community & the North Atlantic area: IO in the light of historical experience. Princeton University Press.

12- Directorate of International and Military Cooperation (DIMC). (2023). Draft doctrine proposal for military diplomacy & foreign military engagement. Lebanese Armed Forces.

13- Delcour, L. (2015). Small states & Euro-Atlantic security: Georgia’s defense diplomacy. European Security, 24(3), 387–405.

14- European External Action Service (EEAS). (2022). EU–Lebanon cooperation. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/

15- Finnemore, M. (1996). National interests in international society. Cornell University Press.

16- French Embassy in Beirut. (2022). France–Lebanon defense cooperation. https://lb.ambafrance.org/

17- French Ministry of Armed Forces. (2023). MTC4L framework.

18- German Federal Foreign Office. (2021). Germany–Lebanon relations. https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/lebanon/227498

19- GIZ Lebanon. (2022). Support to the LAF. https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/324.html

20- House of Commons Defense Committee. (2021). UK military operations in Lebanon: Evidence report. UK Parliament.

21- Italian Embassy Beirut. (2021). Support to the LAF. https://ambbeirut.esteri.it/ambasciata_beirut/en/

22- Italian Ministry of Defense. (2022). Italy–Lebanon defense cooperation. https://www.difesa.it/EN/Pages/default.aspx

23- J5 Planning Directorate. (2022). Annual review of strategic planning & international cooperation activities. Lebanese Armed Forces.

24- J5 Planning Directorate. (2023). Strategic risk assessment brief: Alignment of foreign partner support with national priorities. Lebanese Armed Forces.

25- Katzenstein, P. J. (Ed.). (1996). The culture of national security: Norms & identity in world politics. Columbia University Press.

26- Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (1977). Power & interdependence: World politics in transition. Little, Brown.

27- Krieg, A. (2016). Externalizing the burden of war: The Obama doctrine & the Unite States foreign policy in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan.

28- Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF). (2022). Internal organization manual: Roles & responsibilities of the J5 Directorate & subordinate elements.

29- Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF). (2023–2027). Capability development plan 2023–2027.

30- Lebanese Armed Forces – Directorate of International and Military Cooperation (LAF–DIMC). (2024). Internal communications on capability development & international cooperation. Lebanese Armed Forces.

31- Lebanese Armed Forces – United Kingdom Ministry of Defense (LAF–UK MOD). (2024). Technical arrangement on training and advisory cooperation.

32- Military Technical Cooperation for Lebanon (MTC4L). (2023). Annual report on defense assistance and coordination.

33- Ministry of the Armed Forces of France. (2022). Support to the LAF. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/

34- Ministry of Defense (MoD), Lebanon. (2022). Strategic review of Lebanese defense diplomacy & international engagement. Government of Lebanon.

35- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands (MoFA). (2022). Support to the LAF. https://www.government.nl/ministries/ministry-of-foreign-affairs

36- Morgenthau, H. J. (1948). Politics among nations: The struggle for power & peace. Alfred A. Knopf.

37- NATO. (2021). Lebanon – NATO individual partnership and cooperation programme (IPCP). NATO Headquarters.

38- NATO. (2021). Partnership interoperability initiative: Enhancing compatibility with partner nations. NATO Standardization Office.

39- Sharp, J. M. (2022). Jordan: Background & The Unite States relations (CRS Report No. RL33546). Congressional Research Service.

40- Tardy, T. (2014). CSDP: Getting third states on board. EU Institute for Security Studies. https://www.iss.europa.eu/

41- Technical Arrangement between the United Kingdom Armed Forces and the Lebanese Armed Forces (TA). (2024). PEGASUS CEDAR 2024 exercise agreement. UK Embassy.

42- UNIFIL. (2022). Annual report. https://unifil.unmissions.org/

43- UK Embassy in Beirut. (2024). Crisis note verbal submitted to the MoFA regarding the legal status of UK forces in Lebanon.

44- Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of international politics. Addison-Wesley.

تعزيز التعاون العسكري الدولي كأداةٍ استراتيجية لتطوير القدرات في الجيش اللبناني: إطار للشراكة المستدامة والجهوزية العملانية

يتناول هذا المقال الدور الاستراتيجي الذي يؤديه التعاون العسكري الدولي في تعزيز القدرات العملانية والمؤسساتية للجيش اللبناني. ويؤكّد أن هذا التعاون، عندما يستند إلى إطار وطني منظم وواضح، يمكن أن يشكّل أداة أساسية في عملية تحديث المؤسسة العسكرية وتعزيز الاحترافية والتشغيل المشترك، بما يسد الفجوات الناتجة عن محدودية الموارد مع الحفاظ على السيادة والاستقلال الوطني.

يحلّل هذا المقال مجالات التعاون بين الجيش اللبناني وكل من المملكة المتحدة، فرنسا، الولايات المتحدة، تركيا، والأمم المتحدة، من حيث إسهامها في التدريب وبناء القدرات وتعزيز التوافق الاستراتيجي. كما تبرز الفوائد والتحديات المرافقة لهذه الشراكات، بما في ذلك مخاطر التبعية، وضعف التنسيق المؤسساتي، وغياب سياسة وطنية موحدة لتوجيه أولويات التعاون.

ويخلص هذا المقال إلى أن التعاون العسكري الدولي ساهم بشكلٍ ملموس في تحديث قدرات الجيش اللبناني، خصوصًا في مجالات أمن الحدود، مكافحة الإرهاب، وإصلاح منظومات المساندة اللوجستية، إلا أن غياب الحوكمة المؤسساتية، والأطر القانونية الواضحة، وآليات التقييم المشتركة، يحد من الأثر الاستراتيجي طويل الأمد لهذا التعاون. بناء على ذلك، يقترح كاتب المقال اعتماد سياسة وطنية للتعاون العسكري الدولي وإنشاء المجلس الوطني للتعاون العسكري الدولي (NMCC) لتوحيد الجهود وضمان الشفافية وربط الشراكات الخارجية بالأهداف الدفاعية الوطنية.

كما تهدف الاستراتيجية المتكاملة للتعاون العسكري الدولي (IMCS) إلى تحويل هذا التعاون من عملية ظرفية تقودها الجهات المانحة إلى منظومة شراكة مستدامة تركّز على تطوير القدرات الفعلية. وتؤكد على مبدأَي الملكية الوطنية والانتقائية الاستراتيجية، بحيث تُمنح الأولوية للتعاون الذي يعزز الاستقلالية والجهوزية التشغيلية والتشغيل المشترك، من دون المساس بسيادة الدولة.

في الختام، يبرز هذا المقال أن إدارة التعاون العسكري الدولي بشكلٍ استراتيجي ومنظم ومرتكز إلى القانون والسياسات الوطنية والتنسيق المؤسساتي يمكن أن تحوّل التعاون الدولي من آلية تفاعلية إلى أداة فاعلة لتحقيق التنمية المستدامة للقدرات وتعزيز الدبلوماسية الدفاعية، بما يضمن للجيش اللبناني فاعليته العملانية واستقلال قراره الوطني.