- En

- Fr

- عربي

The Geopolitics of Corridors: The IMEC–BRI Rivalry and the Reshaping of Alliances, Conflicts, and Global Trade

Introduction

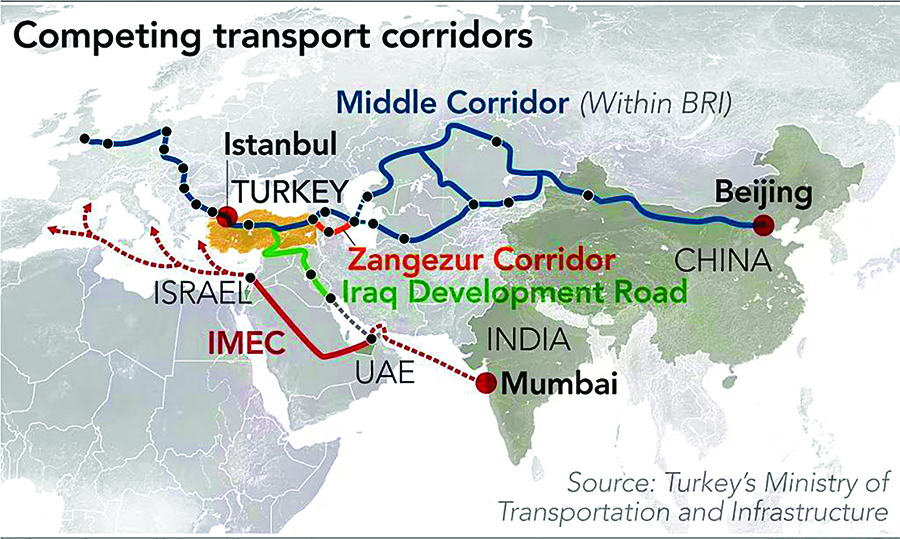

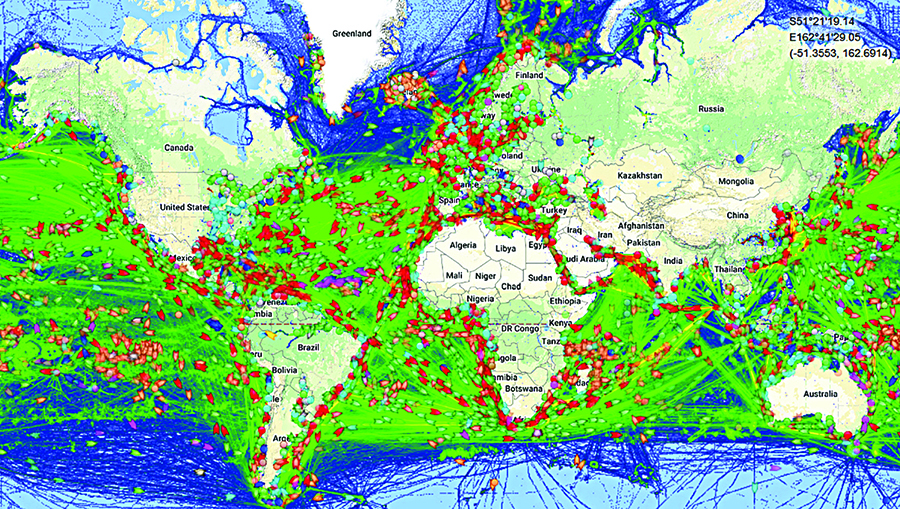

Trade corridors are not neutral infrastructure but geopolitical architectures shaping flows of goods, energy, data, and influence. History shows that routes define power: the Silk Roads enabled empires, the Suez Canal reshaped colonial logistics, and transcontinental railroads shifted continents. Today, two rival visions dominate: China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, which embeds Beijing’s influence across Eurasia, Africa, and key seas, and the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), announced in 2023 with US and EU backing, linking India, the Arabian Peninsula, and Europe. These are not parallel tracks but competing designs for globalization. BRI ties states to China through finance, construction, and port concessions, while IMEC bypasses Pakistan and Iran, elevates India, and transforms Gulf monarchies into multimodal hubs. Both promise prosperity but function as instruments of power that forge alignments, exclude rivals, and create dependencies.1

The mechanics of corridors go beyond diplomacy to freight timetables, energy grids, fiber-optic latency, and port insurance. A container moving from Mumbai to Marseille in four rather than six days reshapes supply chains; a Gulf-Europe hydrogen pipeline redirects investment; Chinese port concessions from Gwadar to Piraeus recalibrate shipping schedules. These technical shifts turn strategy into daily commerce.2 This article examines how IMEC and BRI seek to reshape alliances and conflicts. Chapter One analyzes IMEC’s architecture, sequencing, and political economy; Chapter Two evaluates BRI’s networks, lock-in mechanisms, and regional outcomes. The conclusion assesses which corridor is gaining ground and its implications for Eurasian power. The central thesis is that corridors are self-fulfilling: IMEC could spur Arab-Israeli normalization and make the Gulf the hinge of India-Europe trade, sidelining Pakistan and Iran, while BRI entrenches Chinese influence through sunk costs, equity stakes, and exported standards across Asia and the Mediterranean. Their rivalry will determine not just who profits from logistics but who sets the rules of globalization in the decades ahead.

Chapter One

IMEC: Engineering an India–Gulf–Europe Axis

A. Architecture and Routes

1. The Physical and Digital Spine of IMEC

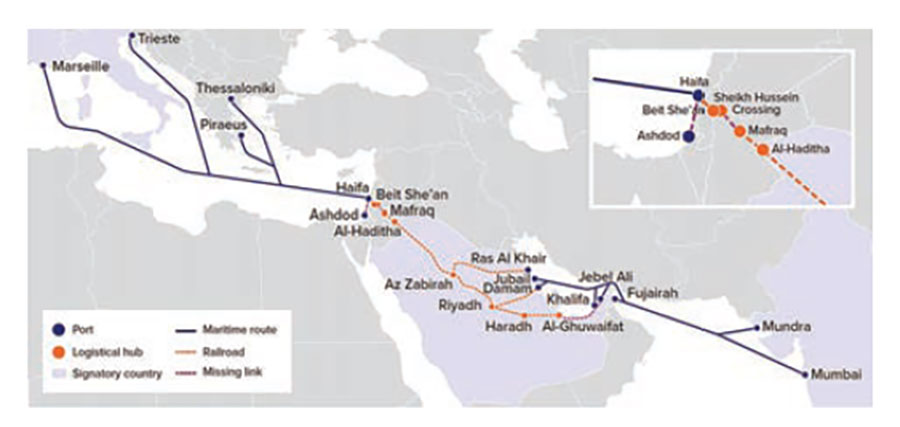

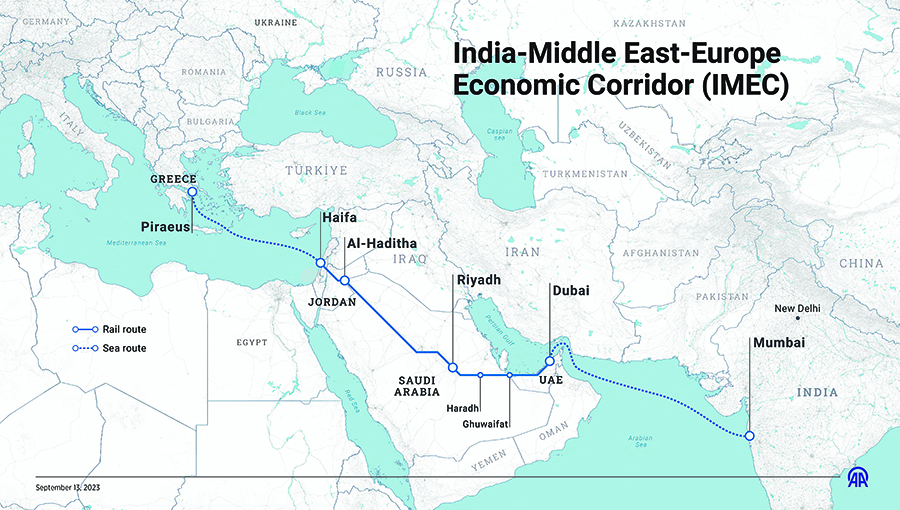

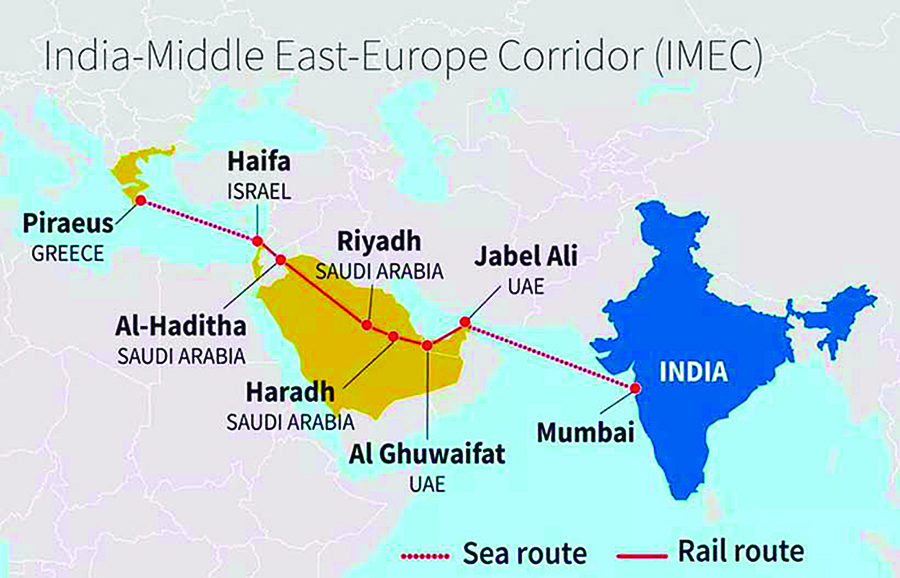

The India Middle East Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is conceived as a multimodal and multilayered network designed not only to transport goods but also to reshape regional power balances. Its structure combines a maritime leg from India’s western ports through the United Arab Emirates with a land corridor across Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel’s Haifa Port, linking further to Europe via short sea shipping. This deliberate configuration bypasses Pakistan and Iran, denying them access to transit rents and integration into westward trade. At the same time, it elevates India and the Gulf monarchies, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, into indispensable hubs of Euro-Asian commerce. For Washington and Brussels, IMEC offers an alternative corridor anchored in pro-Western states, reducing reliance on Chinese-financed projects and politically unstable chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz and the Suez Canal.3

Yet IMEC extends beyond physical transport infrastructure; its deeper ambition is to function as a layered system, and the plans include:

Electricity interconnectors: Proposed upgrades between the UAE and Saudi Arabia, along with Saudi Jordan Israel Europe linkages, would channel surplus Gulf solar energy into European grids.

Hydrogen pipelines: Saudi Arabia’s NEOM Green Hydrogen initiative and the UAE’s export strategies envision pipelines or ammonia conversion delivering Gulf hydrogen to Europe, embedding the region into Europe’s de-carbonization pathway.

Fiber optic corridors: Projects such as the Blue Raman subsea cable, backed by Google to link India to Europe via Israel, highlight IMEC’s digital layer, while alternatives like the PEACE cable show the stakes in data connectivity. Low-latency flows are as strategically important as freight.

Each of these layers reinforces the others: renewable power stabilizes digital continuity, reliable rail timetables anchor just-in-time manufacturing, and long-term hydrogen contracts bind European industry to Gulf suppliers for decades. IMEC therefore seeks to function not as a single transport corridor but as a geopolitical operating system integrating maritime, land, energy, and digital flows. Its design stresses reliability over speed, reflecting lessons from COVID-19 disruptions and the 2021 Suez Canal blockage, where predictability mattered more than raw speed. By prioritizing customs pre-clearance, Authorized Economic Operator recognition, electronic bills of lading, and harmonized port-rail systems, IMEC invests in invisible infrastructures that cut insurance costs, reduce safety stocks, and allow companies to plan with confidence. If realized, IMEC will not only shorten routes but redefine the reliability premium in global trade, transforming trust into traffic and traffic into geopolitical power.4

2. The Physical and Digital Spine of IMEC

The India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is deliberately engineered as a multimodal and multi-layered network, designed not only to move goods but to reconfigure regional power balances. At its core, IMEC consists of two complementary legs that fuse maritime reach with terrestrial continuity.

The eastern maritime leg originates from India’s major western ports: Mumbai (Nhava Sheva/Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust, India’s largest container port), Mundra (operated by the Adani Group), and Kandla. These hubs are already integrated into Asia–Europe trade lanes via the Suez Canal, but IMEC reroutes them strategically toward the United Arab Emirates. Within the UAE, Jebel Ali Port, a DP World-operated mega-facility and one of the top 10 busiest ports globally, and Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi act as the Gulf’s primary transshipment anchors. From these ports, cargo transitions to the northern land corridor: a rail and road system envisioned under Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 National Transport and Logistics Strategy, extending across Saudi Arabia’s Dammam–Riyadh–Tabuk spine into Jordan and then northward to Israel’s Haifa Port on the Mediterranean. Haifa, partly acquired in 2022 by India’s Adani Ports in partnership with Israel’s Gadot Group, becomes IMEC’s structural hinge to Europe. From Haifa, goods move by short-sea shipping to European destinations such as Piraeus (Greece), Trieste (Italy), and Marseille (France).

This deliberate configuration achieves a geopolitical bypass. By excluding Pakistan (traditionally India’s overland rival) and Iran (long a potential corridor for energy pipelines and Eurasian transit), IMEC denies both states the opportunity to collect transit rents and integrate into westward supply chains. Instead, it structurally elevates India and the Gulf monarchies, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as indispensable pivots for Eurasian commerce. For Washington and Brussels, this alignment also creates a corridor anchored in pro-U.S. and pro-EU states, reducing reliance on either Chinese-financed infrastructure or politically unstable chokepoints.5

Yet IMEC is not confined to steel rails and concrete terminals. Its true ambition lies in becoming a layered infrastructure stack. Plans include:

Electricity interconnectors: for example, the UAE–Saudi grid upgrades and Saudi–Jordan–Israel–Europe linkages under discussion, which would allow surplus renewable energy (especially solar from the Gulf) to balance European grids.

Hydrogen pipelines: projects like Saudi Arabia’s NEOM Green Hydrogen initiative and the UAE’s hydrogen export strategies envision molecules traveling via pipeline or ammonia conversion to Europe, embedding Gulf energy into Europe’s de-carbonization plans.

Fiber-optic corridors: including the Blue-Raman subsea cable project (backed by Google, linking India to Europe via Israel) and the PEACE cable (Pakistan & East Africa Connecting Europe), which, although bypassed by IMEC’s design, illustrates the competitive digital stakes. Low-latency data movement is just as geopolitically valuable as containerized freight.

Each of these layers reinforces the others: stable power enables digital continuity; predictable rail timetables anchor just-in-time manufacturing; certified hydrogen exports create 20–30 year supply contracts that bind European industry to Gulf suppliers. In practice, IMEC aims to operate not as a single corridor but as a geopolitical operating system combining maritime, terrestrial, energy, and digital flows into one architecture of influence.6

Crucially, IMEC emphasizes reliability over raw speed. This reflects the hard lessons of modern supply chains, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 Ever Given blockage of the Suez Canal, which exposed the vulnerabilities of a single chokepoint. Manufacturers and logistics firms prioritize variance reduction, the ability to predict with confidence that a container will arrive on Day 4 rather than between Day 3 and Day 6. Thus, IMEC’s protocols stress customs pre-clearance, Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) recognition, electronic bills of lading, and harmonized port–rail interfaces. These “invisible infrastructures” are often more decisive than the construction of a new terminal. They enable shippers to reduce safety stock, lower insurance costs, and plan supply chains around stable calendars.

In this sense, IMEC is more than a corridor; it is an attempt to redefine the reliability premium in global trade. If it succeeds, it will not simply shorten distances; it will reorder trust in logistics networks. Trust, in turn, manufactures traffic, and traffic manufactures power.7

B. Intended Effects on Alliances and Conflicts

1. Manufactured Winners and Structural Losers

Every economic corridor is also a political sorting mechanism: it determines which states capture rents and which are sidelined. IMEC’s blueprint is designed to manufacture a group of clear winners while structurally disadvantaging others.

India is perhaps the most conspicuous beneficiary. For decades, its westward connectivity has been constrained by geography and rivalry. Pakistan’s refusal to allow overland trade with India, and Iran’s oscillation between engagement and sanctions, left New Delhi heavily reliant on sea routes via the Suez Canal or on Chinese-dominated regional logistics. IMEC changes that equation. By linking Mumbai and Mundra directly to Haifa through Gulf and Levantine nodes, India secures a reliable artery to Europe that bypasses its two continental rivals. The strategic effect is twofold: India diversifies away from Chinese-controlled supply chains and gains credibility as an alternative hub in Asia–Europe trade.

For the Gulf monarchies, IMEC transforms geography into a multi-resource rentier model. Saudi Arabia and the UAE no longer collect revenue solely from hydrocarbons but also from ports, bonded logistics zones, rail concessions, and data cables. Jebel Ali, already one of the busiest container ports globally, would see its role expand as the natural interchange between Indian exporters and European importers. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 explicitly envisions Riyadh as a global logistics platform, and IMEC operationalizes that ambition by threading its railway backbone through Saudi territory. By layering hydrogen pipelines, cloud services, and digital certification schemes on top of ports and rail yards, the Gulf rebrands itself as an energy–logistics–data triad at the heart of Eurasia.8

Jordan and Israel, historically peripheral to transcontinental trade, become indispensable hinges in the Levantine land bridge. For Jordan, whose economy has long depended on aid and remittances, IMEC promises to turn its desert geography into a corridor asset. Industrial parks and dry ports along the Amman–Haifa route could tie the kingdom more closely to European and Gulf value chains. For Israel, the corridor is transformative. Haifa Port, now operated by a consortium led by India’s Adani Group, is not simply a terminal; it is the Mediterranean gateway of IMEC. This makes Israel’s security directly tied to corridor stability: escalation in Gaza or with Hezbollah in southern Lebanon now threatens not just national defense but the viability of a transcontinental artery. In this way, IMEC embeds Israel into Arab–Indian–European commerce, reinforcing normalization dynamics initiated by the Abraham Accords.

Europe also emerges as a winner, though in subtler ways. The European Union has long sought to reduce its reliance on Russian energy corridors and on Chinese-operated Mediterranean hubs such as Piraeus. IMEC offers an alternative. By directing traffic into EU-friendly ports like Marseille, Trieste, and Genoa, the corridor strengthens Europe’s supply chain diversification strategy under the Global Gateway initiative. The hydrogen pipeline component further binds Gulf renewable projects to European decarbonization efforts, ensuring long-term energy interdependence.

The losers are just as significant. Pakistan, excluded from IMEC by design, doubles down on the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Gwadar Port, upgraded under Chinese financing, is touted as a rival gateway to the Arabian Sea. Yet the project has struggled with insurgency, lack of hinterland connectivity, and investor hesitation. By bypassing Pakistan entirely, IMEC reduces the geopolitical leverage Islamabad once hoped to wield as the “natural bridge” between South Asia and the Middle East.9

Iran, similarly marginalized, advances its own alternatives. The Chabahar Port, developed with Indian participation, was once imagined as India’s bridge to Afghanistan and Central Asia. Sanctions, however, crippled progress. Tehran now seeks to reposition through the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), linking Iranian ports with Russia via the Caspian. While symbolically important, INSTC cannot match the commercial scale or insurance stability that IMEC promises.

Yet neither Pakistan nor Iran are passive victims. They remain capable of leveraging geography through obstruction or alignment with China and Russia. Still, logistics markets are unsentimental. Shippers and insurers will gravitate toward the corridor that minimizes variance, delays, and risk premiums. If IMEC consistently offers lower insurance rates, predictable timetables, and EU-certified energy flows, then political sympathy for alternative routes will not compensate for commercial disadvantage.

Infrastructure exerts its own gravitational pull. Once companies restructure supply chains around reliable routes, habits harden into dependency. Reliability manufactures trust, and trust manufactures traffic. In this sense, IMEC is not merely designing winners and losers in the present; it is writing the future map of Eurasian commerce, one container, pipeline, and data packet at a time.10

2. Risk Engineering: Peace Premiums and Interoperability

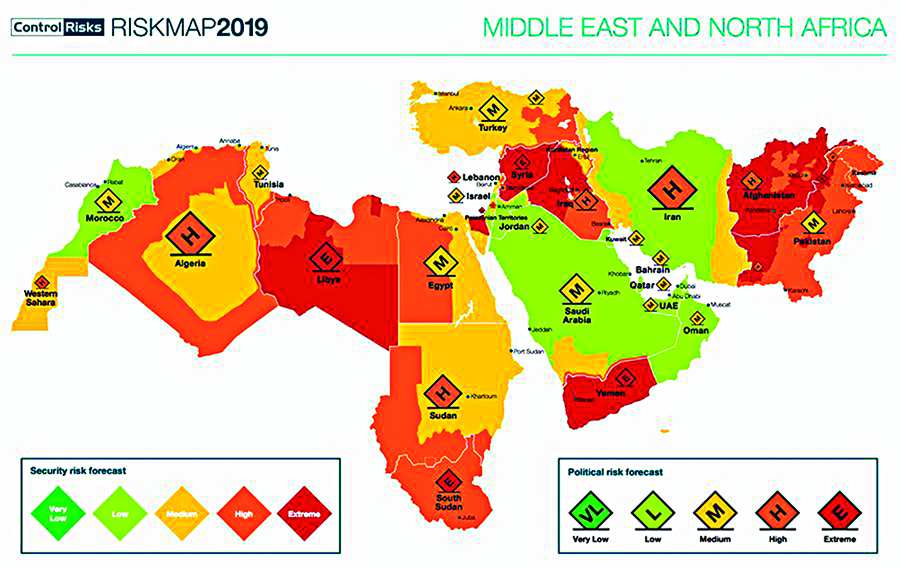

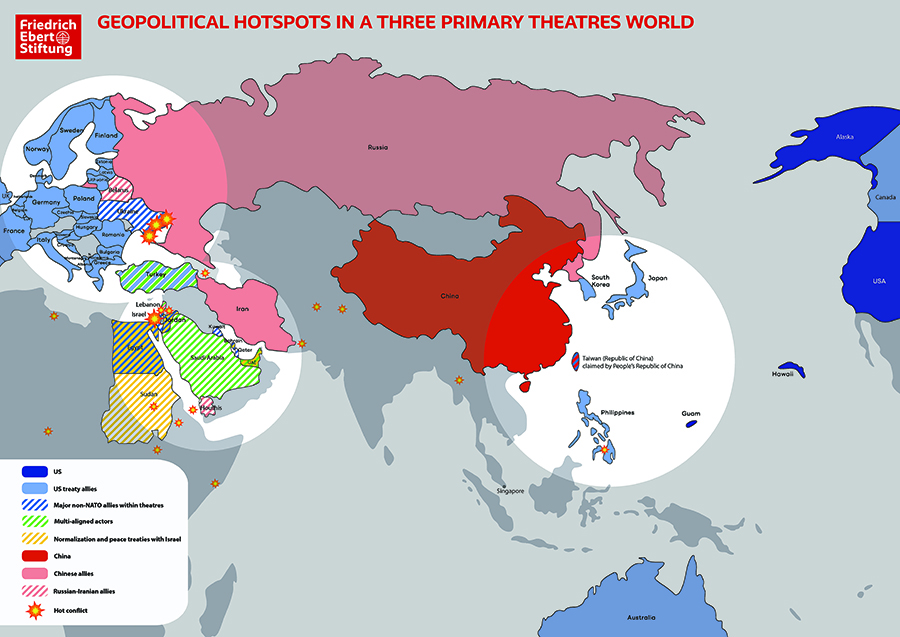

Unlike corridors that traverse relatively stable territories, IMEC runs through one of the most politically volatile regions on earth. Its northern leg crosses the Saudi–Jordanian border, the Jordan–Israeli frontier, and finally the contested Levant, all regions historically marked by wars, insurgencies, and recurring diplomatic crises. This makes IMEC not only a logistical project but a geopolitical gamble: every flare-up in Gaza, every Hezbollah–Israel exchange along the Blue Line, and every missile attack in the Red Sea translates directly into higher war-risk insurance premiums, broken schedules, and loss of competitiveness compared with maritime routes through the Suez.

This structural fragility produces what analysts call a peace premium. In simple terms, IMEC turns stability into something that can be commercially monetized. If borders remain calm, the corridor’s insurance costs drop, timetables are predictable, and freight forwarders flock to it. If conflict erupts, the corridor quickly becomes unviable. Unlike the BRI, which relies on redundancy and multiple routes, IMEC concentrates value in a single narrow chain that is only as strong as its weakest political link.11

Engineering this peace premium requires layered resilience measures across multiple dimensions.

Physical resilience: Rail yards in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel will need to be built to military-grade specifications, with hardened signaling systems resistant to sabotage or cyber-attack. Multiple Mediterranean gateways; Haifa, but also possible alternatives in Ashdod, Limassol, or Trieste, must provide redundancy in case one port is disrupted. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plans already envision rail extensions protected by surveillance and drone systems to secure against insurgent attacks in border regions.

Administrative resilience: Stability cannot be guaranteed by infrastructure alone. Corridor participants must develop shared incident-response protocols, rapid customs re-routing procedures, and intelligence exchange agreements. Without cross-border coordination, even minor disruptions could cascade into full-scale supply chain breakdowns. For example, a cargo delay at the Jordan–Israel crossing could throw off entire shipping schedules into Europe if there are no joint contingency procedures.

Commercial resilience: Insurers will play a central role. One model being discussed involves insurance-indexed contracts, where risks are pooled among states, carriers, and underwriters instead of concentrated on a single operator. This ensures that disruptions do not bankrupt shippers and encourages companies to commit to the corridor despite its volatile geography. London-based insurers have already indicated that premium reductions could be tied to the presence of multinational monitoring forces along sensitive stretches.

Interoperability is the second pillar of resilience. A corridor that depends on five or six sovereign actors cannot afford to stumble on technical mismatches. Rail systems must harmonize axle loads, signaling technology, and safety standards to allow seamless movement from Jebel Ali through Riyadh and Amman to Haifa. Power grids need synchronization so that electricity interconnectors can stabilize fluctuations when Gulf solar energy is fed into Levantine or European networks. Hydrogen exports must be certified under the European Union’s Guarantees of Origin system to ensure they qualify as “green” in European carbon markets. Digital standards, from customs data to the Blue-Raman subsea cable, must align with EU and U.S. cybersecurity requirements, excluding Chinese or Russian platforms from critical nodes.

The lesson is clear: IMEC’s success will not be judged by ribbon-cutting ceremonies or memoranda of understanding, but by whether global manufacturers and shipping firms can confidently price it into their supply chains. If a container can leave Nhava Sheva and reach Trieste with predictable costs and schedules, without unnecessary handoffs, hidden surcharges, or political delays, then IMEC will thrive. If not, it risks becoming yet another visionary project that falters at the intersection of geopolitics and logistics.12

Chapter Two

The Silk Roads: Consolidating China’s Connectivity Web

A. Overland and Maritime Networks

1. The Six Overland Corridors and Their State Sequences

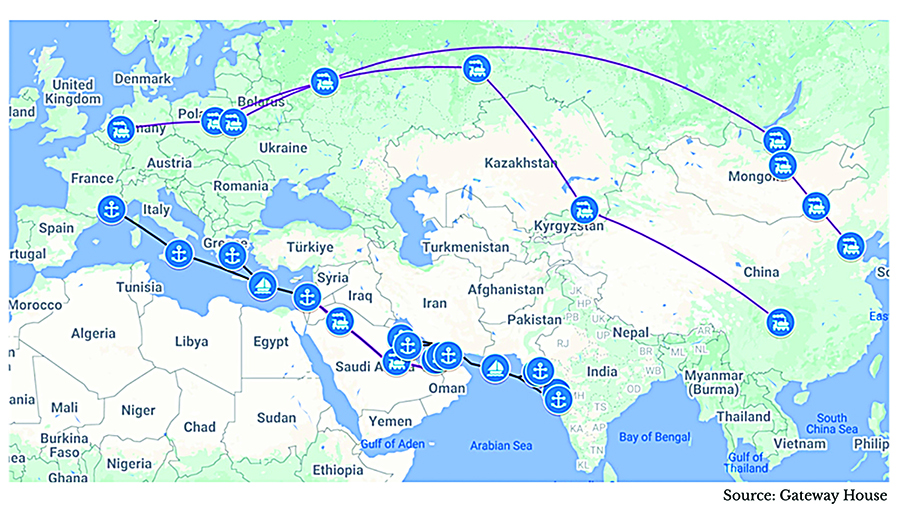

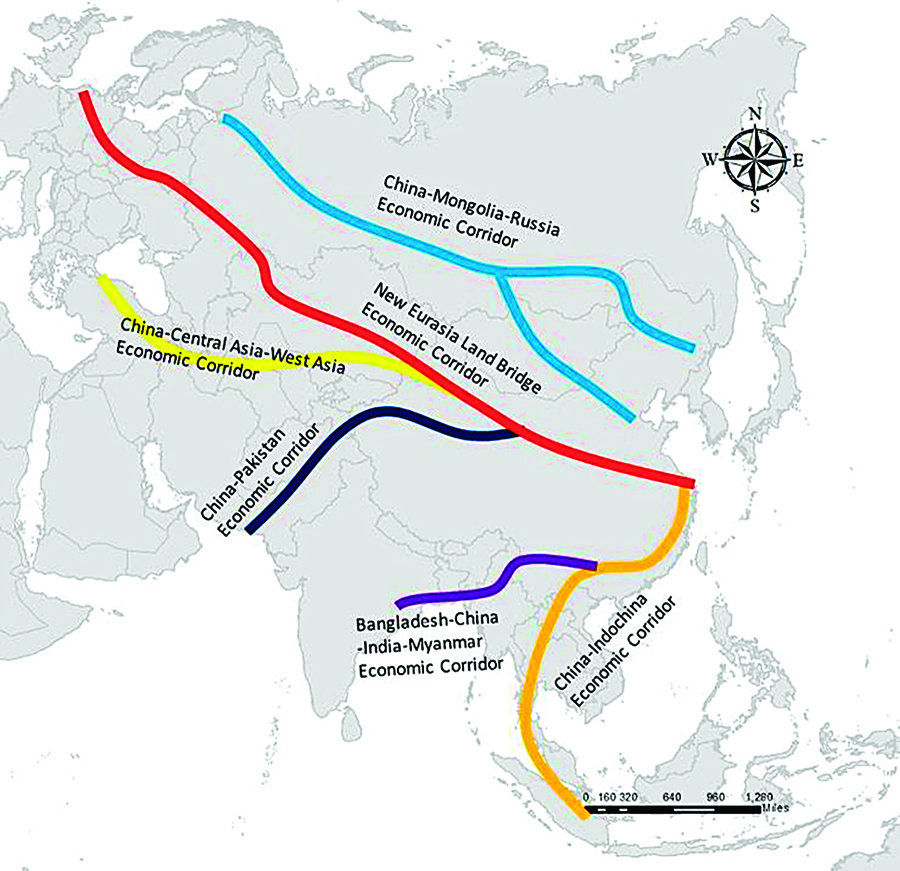

The overland component of the Belt and Road Initiative is structured as a lattice of six principal corridors, each designed to reduce China’s vulnerability to chokepoints and embed Beijing as the indispensable hub of trans-Eurasian connectivity. Far from being symbolic, these corridors represent hundreds of billions in railways, dry ports, energy grids, and industrial parks, creating a physical and financial architecture that endures political shocks.13

a. New Eurasian Land Bridge

This flagship corridor links eastern China through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland into the European core markets of Germany and the Netherlands. It carries container trains such as the Chongqing–Duisburg Express, which has become emblematic of Sino-European rail trade. Critical nodes include the Khorgos Gateway dry port on the Kazakh–Chinese border and Brest (Belarus), where the gauge transition from standard (1,435 mm) to Russian broad gauge (1,520 mm) is managed. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, this route surged in popularity as air freight collapsed and maritime shipping faced delays, proving its commercial viability. However, the Ukraine war and Western sanctions on Russia have complicated flows, pushing shippers to seek alternatives through the South Caucasus.14

b. China–Mongolia–Russia Corridor

This alignment connects Inner Mongolia’s border hubs such as Erenhot to the Trans-Siberian Railway, providing redundancy for east–west cargo flows. For China, Mongolia offers not just transit but access to mineral wealth, especially coal and copper. Russia benefits by monetizing its vast but underutilized rail network. Politically, this corridor underscores Beijing’s balancing act: maintaining ties with Moscow despite sanctions while quietly preparing parallel routes through Central Asia to avoid over-dependence.15

c. China–Central Asia–West Asia Corridor

Stretching westward from Xinjiang through Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran, this corridor connects into Türkiye and the Mediterranean. It includes spurs across the Caspian Sea: ferries from Aktau (Kazakhstan) to Baku (Azerbaijan), onward by rail to Georgia’s Anaklia or Batumi ports, and finally through Türkiye into Europe. This so-called Trans-Caspian Middle Corridor has gained attention since 2022, as shippers sought alternatives to Russian routes. The inclusion of Iran adds strategic depth, giving China direct access to Persian Gulf energy and to a sanctions-defiant partner eager for investment.16

d. China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

Perhaps the most politically visible of the six, CPEC runs from Kashgar in Xinjiang through the precarious terrain of Gilgit-Baltistan, down Pakistan’s central spine via Lahore and Islamabad, and finally to the ports of Karachi and Gwadar. It bundles highways, power plants, fiber-optic cables, and Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Gwadar, often portrayed as China’s potential “pearl” in the Indian Ocean, offers direct Arabian Sea access, reducing reliance on the Strait of Malacca. Yet insurgencies in Balochistan, militant attacks on Chinese workers, and local discontent with economic exclusion highlight the corridor’s risks. For Beijing, CPEC is not just about trade but about securing an energy lifeline that bypasses the vulnerable Malacca chokepoint.17

e. China–Indochina Peninsula Corridor

This route extends southward from Yunnan Province into mainland Southeast Asia, passing through Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, and ultimately Singapore. Its flagship is the China–Laos Railway, inaugurated in 2021, which provides a direct land connection from Kunming to Vientiane. Planned extensions into Thailand and Malaysia could eventually form a continuous rail spine linking southern China with the Strait of Malacca, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. This corridor is less about Europe and more about embedding China into ASEAN’s supply chains, thereby reshaping the economic geography of Southeast Asia.18

f. Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Corridor (BCIM)

Initially envisioned to link Kunming with Kolkata via Myanmar and Bangladesh, this project has stalled due to India’s reluctance to participate in a corridor perceived as a threat to its sovereignty. The concept has since been scaled back, focusing instead on Yunnan–Myanmar connections through Muse–Mandalay, with potential linkage to Indian Ocean ports. Although truncated, the BCIM corridor illustrates Beijing’s ambition to penetrate South Asia’s logistics despite New Delhi’s resistance.19

Resilience through Redundancy

These corridors are not rigid blueprints but flexible option sets. When geopolitical shocks alter costs, Chinese planners simply reroute. The Ukraine war forced adjustments: cargo that once moved across Russia and Belarus increasingly travels via the Trans-Caspian Middle Corridor (Kazakhstan–Caspian ferry–Azerbaijan–Georgia–Türkiye). By investing in multiple spurs, Beijing ensures that no single rupture cripples the system.

The virtue of a network lies in its resilience. With sunk costs spread across dry ports like Khorgos, rail hubs like Almaty and Urumqi, and industrial parks in places like Duisburg and Gwadar, China holds a diversified logistics portfolio. This portfolio approach means that even when one route becomes politically toxic or commercially risky, others absorb the flow. In effect, the BRI’s six overland corridors operate as parallel insurance policies for China’s grand strategy: ensuring that its goods, capital, and influence continue to circulate regardless of sanctions, wars, or diplomatic freezes.20

2. The Maritime Silk Road: Ports, Concessions, and Dual-Use Externalities

China’s Belt and Road Initiative extends beyond railways and pipelines to a maritime “string of pearls” assembled through state-owned giants like CMPort, COSCO Shipping Ports, and CHEC. This network of stakes, concessions, and terminals spans Kuantan and Port Klang in Malaysia, Colombo and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Gwadar in Pakistan, Duqm in Oman, Djibouti, Mombasa in Kenya, Port Said and Suez in Egypt, and Piraeus in Greece. Each is commercially justified by location on sea lanes, chokepoints, or consumer markets, yet together they expand China’s logistical and potential military reach from the Indo-Pacific into Europe. These ports are acquired through long concessions (30–99 years), concessional loans, joint ventures, and bundled infrastructure, then standardized with Chinese yard systems, gantry cranes, and digital platforms. Such harmonization attracts carriers and forwarders, boosting throughput—Colombo became a transshipment hub and COSCO’s management of Piraeus elevated it to one of Europe’s busiest gateways. Commercial upgrades yield strategic spillovers: deep berths can host naval ships, repair docks can serve auxiliaries, and logistics parks double as military depots. Djibouti exemplifies this shift with China’s first overseas military base in 2017, while ports like Gwadar and Hambantota already hold the capacity for PLAN visits despite political sensitivities.21

The Maritime Silk Road is reinforced by the Digital Silk Road, overlaying subsea cables, satellite ground stations, and cloud infrastructure on port hubs. The PEACE cable links Gwadar and Djibouti to Europe, while Huawei Marine builds data centers near logistics sites, fusing physical trade with digital flows to reduce latency and boost Chinese exporters’ competitiveness. Once logistics chains, customs software, and port operations adopt Chinese systems like COSCO’s Navis or CMPort’s platforms, they become entrenched, making alternatives costly to implement. Thus, China exports not just infrastructure but rules, standards, and operating routines that bind partner states into its ecosystem for decades. This creates a dual-layered maritime sphere of influence: visible assets (ports, cranes, berths, warehouses) and invisible standards, data, and contracts. Together, they extend Beijing’s power far beyond its shores, merging commercial necessity with strategic leverage.22

B. Strategic Logic and Regional Outcomes

1. Mechanisms of Influence: Finance, Sunk Costs, and Standards Export

The Belt and Road Initiative’s most potent mechanism of influence is not flashy ribbon-cutting ceremonies but the quiet entanglement of finance and operations. Beijing’s state-owned policy banks, led by the China Development Bank and the Export–Import Bank of China, extend loans to host governments and state utilities. These loans often come bundled with Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contracts that mobilize Chinese firms such as China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC), or Power China. Concession agreements then hand operational control of ports or industrial zones to firms like COSCO Shipping Ports or China Merchants Port Holdings for terms stretching 30 to 99 years.

The result is a triple lock: governments incur debt obligations; Chinese firms control the construction process; and Chinese operators manage facilities over decades. Even if political leadership in a host country shifts, these sunk investments make withdrawal difficult. Physical networks exert their own gravitational pull. Railways, once aligned toward a Chinese-built dry port, naturally channel freight through that node. Power plants fueled by Chinese technology require compatible spare parts and technicians. Over time, infrastructure generates dependency by sheer momentum.23

The case of Piraeus Port in Greece illustrates this dynamic. COSCO first entered through a concession in 2009, at the height of Greece’s debt crisis, and later expanded its stake to a majority holding. Despite repeated debates in Athens and Brussels about national security and European sovereignty, the port’s throughput has surged. Container traffic multiplied, transforming Piraeus into one of the busiest hubs in the Mediterranean. Political ambivalence remains, but commercial gravity now outweighs ideological resistance. Ships call where capacity is reliable, and carriers reorganize around standardized COSCO systems. This is how the BRI translates finance into strategy: sunk costs produce routines, routines produce habits, and habits evolve into power.

A second mechanism is the export of standards, often less visible but equally constraining. Chinese firms embed their own digital and operational ecosystems abroad. Port Internet of Things (IoT) systems, developed by Huawei or ZPMC, manage crane operations, yard movements, and customs data. Digital platforms for bills of lading and shipment tracking, pioneered in Chinese mega-ports, are replicated in overseas concessions. Once local operators and freight forwarders adapt to these systems, the cost of switching becomes prohibitive. A port that digitizes its workflow around COSCO’s Navis or Huawei’s platforms cannot easily migrate to European or American alternatives without disrupting entire supply chains.

This dynamic extends beyond ports. Smart-city projects in Africa use Chinese surveillance and traffic management systems; special economic zones deploy Chinese enterprise software; energy grids synchronize with Chinese-made turbines and monitoring systems. Each of these standards becomes a distribution channel for Chinese norms. Unlike a military base, which is obvious and politically contestable, standards seep quietly into daily commercial life. They shape how cargo is handled, how data is stored, and how contracts are enforced.

The genius of the BRI is thus not merely in building infrastructure but in embedding operational path dependence. Finance ensures projects are approved; sunk costs make them politically irreversible; standards export locks in long-term technological alignment. Together, these mechanisms transform concrete and steel into enduring instruments of geopolitical leverage.24

2. Who Is Winning Where: A Theater-by-Theater Assessment

The contest between the Belt and Road Initiative and IMEC is not uniform; it plays out differently across theaters. Each geography produces its own balance of winners, losers, and hedgers.

Pakistan and the Arabian Sea

In Pakistan, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) makes the BRI the undisputed framework. From Kashgar in Xinjiang to Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea, CPEC bundles energy projects, highways, and fiber-optic cables financed and executed by Chinese firms. Gwadar, operated by the China Overseas Port Holding Company, is marketed as a future transshipment hub linking western China to Middle Eastern energy. Despite persistent insurgencies in Balochistan and attacks on Chinese workers, sunk costs in power plants, motorways, and port facilities anchor Pakistan’s dependency. Islamabad has little alternative financing and is deeply indebted to Chinese lenders, ensuring Beijing’s primacy in this theater.25

India and Europe

For India, IMEC is a structural escape hatch. By running directly westward through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel, IMEC bypasses both Pakistan and Chinese-dominated hubs. If the corridor delivers on reliability, customs pre-clearance, and harmonized standards, it will tilt Eurasian trade flows in India’s favor. This matters strategically: Indian exporters currently depend on the Suez Canal route, which is vulnerable to blockages and competition from Chinese shipping alliances. IMEC would give India a geopolitical dividend, not just shorter transit, but symbolic elevation as the Asian anchor of a Western-aligned corridor. For Europe, the benefit is equally clear: IMEC offers entry points in Trieste, Marseille, or Genoa, avoiding reliance on Chinese-controlled Piraeus while diversifying away from Russian disruption of Eurasian land routes.26

The Gulf

The Gulf monarchies remain the hedgers-in-chief. Chinese capital is deeply embedded in regional infrastructure: COSCO Shipping operates in Abu Dhabi’s Khalifa Port; Sinopec and CNPC hold stakes in Saudi and Emirati refineries; and Huawei builds digital infrastructure in the region. At the same time, IMEC promises new rents: hydrogen pipelines, data cables, and railway concessions. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 explicitly seeks to transform the kingdom into a logistics hub, while the UAE positions Jebel Ali and Khalifa as natural junctions for India–Europe trade. The Gulf will not “choose” between BRI and IMEC; instead, it will arbitrage both, extracting concessions and securing investment from Beijing, Washington, Brussels, and New Delhi alike.27

Central Asia and the Caucasus

In Central Asia, the BRI remains dominant, with Chinese-built railways, pipelines, and industrial parks in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. The Khorgos Gateway on the Kazakh–Chinese border stands as the flagship dry port of Sino-European rail. Yet the Ukraine war and sanctions on Russia have revived the Trans-Caspian “Middle Corridor”: cargo moves from Kazakhstan across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Türkiye, supported by European Union investments and Turkish logistics networks. This route is slower and more expensive than the northern path through Russia, but it provides risk-averse shippers a politically acceptable alternative. For China, this redundancy is costly but manageable; for Europe and Türkiye, it is a strategic wedge into a region otherwise dominated by Beijing.28

The Mediterranean

The Mediterranean is a contested frontier. The BRI’s strongest foothold is Piraeus Port in Greece, where COSCO transformed a debt-ridden facility into one of Europe’s busiest container gateways. Piraeus remains a jewel in Beijing’s maritime portfolio, complemented by stakes in Valencia and Zeebrugge. Yet IMEC’s European terminus could rebalance this equation. If traffic is directed into Trieste (Italy), Marseille (France), or Genoa (Italy), Europe gains new entry points under EU-aligned operators, reducing dependency on Chinese-run assets. The contest here is not only about volume but about normative alignment: whether Europe’s future maritime gateways conform to EU standards or remain tied to Chinese systems.29

Israel’s Role in the Levant

One additional pivot lies in Israel. IMEC’s northern land leg terminates at Haifa Port, operated jointly by India’s Adani Ports and Israel’s Gadot Group. This makes Israel a structural hinge in IMEC, linking Gulf exporters and Indian manufacturers to European markets. For Tel Aviv, this is both an opportunity and a liability: normalization with Arab states is strengthened, but the corridor’s viability is threatened by conflicts with Hamas in Gaza or Hezbollah in Lebanon. China, meanwhile, also retains a footprint in Israel through its earlier investments in port and rail projects, meaning Israel straddles both systems.30

Conclusion

Corridors are not neutral highways; they are instruments of strategic design. They determine which states become hubs, which become cul-de-sacs, and which are written out of the map altogether. By comparing IMEC and BRI, we see two contrasting models of connectivity and two different strategies of power.

IMEC is a corridor of inclusion and exclusion. It deliberately elevates India, the Gulf monarchies, Israel, and European markets while excluding Pakistan and Iran. Its success depends on interoperability and stability: synchronized rail systems, harmonized customs, trusted digital standards, and insurable routes. It creates a commercial constituency for peace by making conflict economically costly. If the Levant is calm, the corridor thrives; if it is turbulent, the corridor collapses. This built-in fragility is also its leverage: by turning stability into profit, IMEC makes peace not just a political aspiration but a commercial requirement.

BRI, by contrast, is a corridor of consolidation and lock-in. It binds Pakistan, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe into a China-centric network through sunk costs, port concessions, and digital standards. Its strength is resilience: with multiple land bridges and maritime pearls, no single disruption can cripple it. Its weakness lies in overextension, debt burdens, and reputational backlash in some host countries. Yet the gravity of installed assets (ports, railways, and power plants) keeps drawing traffic regardless of political rhetoric.

Who is “winning”? At present, BRI enjoys structural depth. It has more built assets, a wider reach, and stronger entanglements. But IMEC carries political momentum, especially with U.S., EU, Indian, and Gulf backing. Its test is delivery: can it move from G20 communiqués to schedulable trains, certified hydrogen molecules, and low-latency digital cables?

The next decade will likely see competitive coexistence rather than outright victory. Firms will choose routes based on reliability, cost, and insurance premiums, not ideology. Yet behind each choice lies geopolitics: whether a shipment moves through Gwadar or Haifa is not only a matter of logistics but of alignment. In this sense, corridors write politics into geography.

The rivalry between IMEC and BRI is, at its core, about who gets to define the operating system of globalization in the 21st century. Will Eurasia’s arteries pulse to Chinese finance and standards, or will an India–Gulf–Europe axis backed by Western powers carve a counter-design? The answer will not be decided in summits alone, but in the quiet metrics of minutes saved at ports, insurance points shaved from war-risk premiums, and containers reliably arriving on time. On those margins, the future balance of power will be built: train by train, ship by ship, and byte by byte.

Bibliography

Books

1. Nag, K. (2021). A new Silk Road: India, China and the geopolitics of Asia. Rupa Publications.

2. Tharoor, S. (2012). Pax Indica: India and the world of the twenty-first century. Penguin Books India.

3. Dalrymple, W. (2024). The golden road: How ancient India transformed the world. Bloomsbury Publishing.

4. Stopford, M. (2009). Maritime economics (3rd Ed.). Routledge.

5. Alderton, P. M. (2008). Port management and operations (3rd Ed.). Informa Law/Routledge.

6. Yergin, D. (2020). The new map: Energy, climate, and the clash of nations. Penguin Press.

7. Flyvbjerg, B., & Gardner, D. (2023). How big things get done. Crown.

8. Grammenos, C. T. (Ed.). (2013). The handbook of maritime economics and business (2nd ed.). Informa Law/Routledge.

9. Mangan, J., & Lalwani, C. (2016). Global logistics and supply chain management (3rd Ed.). Wiley.

10. Burnett, D. R., Beckman, R. C., & Davenport, T. M. (Eds.). (2014). Submarine cables: The handbook of law and policy. Brill Nijhoff.

11. Kennedy, A. B., & Lim, D. J. (2018). The political economy of international infrastructure. Palgrave Macmillan.

12. Wolf, S. O. (2019). The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative. Springer.

13. Curtis, S., & Klaus, I. (2024). The Belt and Road city. Yale University Press.

14. Li, S., & do Nascimento, D. F. (2022). The Belt and Road Initiative in South–South cooperation. Springer.

15. Heiduk, F. (2023). Asian geopolitics and the US–China rivalry. Routledge.

16. Li, X., & Lim, L. (2023). China’s communication of the Belt and Road Initiative. Routledge.

17. Arase, D., Carvalho, P. M. A. R., et al. (2024). The Belt and Road Initiative in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Routledge.

18. Moldicz, J., Karalekas, D., & Liu, F.-K. (2025). Middle-power responses to China’s BRI. Palgrave.

Journal Articles

1. Singh, S., Raja, W., Kumar, S., & Uppal, A. (2024). India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor: A strategic energy alternative. Scholastica Quarterly, 10(2), 50–71.

2. Simonov, M. (2025). The Belt and Road Initiative and Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment. Global Strategy Journal, 15(2), 110–136.

3. García-Herrero, A. (2024). What determines global sentiment towards China’s Belt and Road Initiative? Asia Europe Journal, 22, 100–120.

4. Zhao, M. (2021). The Belt and Road Initiative and China–US strategic competition. Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 4(3), 45–67.

5. American Strategy Journal. (2024). China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Economic development or geo-economics strategy? American Strategy Journal, 12(6), 973–995.

6. Journal of International Affairs. (2022). Assessing China’s motives: How the Belt and Road Initiative threatens US interests. Journal of International Affairs, 75(1), 90–113.

7. Central Asian Survey. (2023). Trade, infrastructure and neighbourhoods: BRI’s effect on Central Asia & the Caucasus. Central Asian Survey, 39(2), 120–142.

8. Journal of International Economics. (2023). Rail corridors and economic development. Journal of International Economics, 150, 102–123.

9. Energy Policy. (2016). Energy corridors, pipelines and power politics. Energy Policy, 95, 330–345.

Reports and Research Papers

1. Gunter, J. (2023). China’s footprint in global port ecosystems. MERICS China Monitor, 4(1), 1–25.

2. International Institute for Strategic Studies. (2022). The Belt and Road Initiative – Strategy and Implementation. IISS Strategic Dossier, 1, 3–52.

3. MERICS. (2023). How the BRI is shaping global trade and what to expect in its second decade. MERICS.

صعود الممرات: التنافس الجيو - سياسي بين الممر الهندي - الشرق الأوسط - أوروبا (IMEC) ومبادرة الحزام والطريق (BRI)

النقيب موسيس نشاليان

في شبكة التفاعلات المعقدة للجغرافيا السياسية العالمية، يبرز التنافس بين الممر الهندي - الشرق الأوسط - أوروبا (IMEC) ومبادرة الحزام والطريق (BRI) كأداة رئيسة لإعادة صياغة موازين القوى والتحالفات، حيث تمثل الأولى مشروعًا مدعومًا غربيًا حديث العهد، بينما تجسد الثانية المبادرة الصينية الأوسع نطاقًا والأقدم زمنًا. فقد أطلقت الصين مبادرة الحزام والطريق (BRI) عام 2013 عبر شبكة مترابطة من الممرات البرية والبحرية، ثم أُعلن الممر الهندي - الشرق الأوسط - أوروبا (IMEC) عام 2023 بدعم الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروبي كبديل منافس يربط الهند بأوروبا عبر الخليج والأردن و«إسرائيل»، مستبعداً باكستان وإيران، ما يحوّل الخليج إلى محور للطاقة واللوجستيات والاتصالات الرقمية. ويتجسد طموحه في الربط بين الموانئ، شبكات الكهرباء، أنابيب الهيدروجين، والكابلات البحرية، في إطار رؤية تهدف إلى تعزيز موثوقية التجارة العالمية.

في المقابل، تُعد مبادرة الحزام والطريق (BRI) مشروعًا صينيًا أوسع وأعمق، يمتد عبر ستة ممرات برية وطريق بحري من آسيا إلى أفريقيا وأوروبا، مرتكزًا على استثمارات في الموانئ والسكك الحديدية وشبكات الاتصالات. وتكمن قوتها في التنوع والمرونة، إذ توفر بدائل متعددة لتجاوز الأزمات، وتُرسّخ ارتباط الدول المستضيفة عبر الديون والمعايير التقنية الصينية.

أما بنية الممر الهندي - الشرق الأوسط - أوروبا (IMEC) فتُفرز فائزين بارزين كالهند، الخليج، وأوروبا، بينما تهمش باكستان وإيران. في حين أن مبادرة الحزام والطريق (BRI) تعمّق النفوذ الصيني من خلال الارتباط طويل الأمد والأصول الثابتة. وبذلك، يتحدد الصراع بين الممرين كعامل مؤثر في تشكيل العولمة المقبلة، بين مسار تقوده بكين قائم على الترسخ والاعتماد، وآخر تدعمه الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروبي يعزز مكانة الهند والخليج ويحوّل الاستقرار الإقليمي إلى شرط تجاري. النتيجة هي تنافس مستدام يرسم خريطة النفوذ لعقود قادمة.