- En

- Fr

- عربي

External support in conflicts

Introduction

One assumption that rules the fight between states and non-state actors in intrastate conflicts is that: state actors start the conflicts with a significant force advantage over non-state actors; on the opposite, non-state actors have an information advantage over state actors. Another assumption that rule wars in general are that: force and information are positively correlated; meaning that, as the force of an actor grows bigger, its stealth will decrease and the information about this actor will increase.

There is an ongoing debate between strategic decision leaders about the effect of sending external support in intrastate conflicts around the globe. In one view, one would think that external support should help the receiver actors in their fight, would deter adversaries, and make it simple for these actors to attain their objectives with the use of foreign supports. Advocates of this view support expanding and continuing sending external support in intrastate conflicts. Another view holds that sending support will backfire and decrease the likelihood of winning in conflict and tends to provoke adversaries and raise patriotism. Advocates of this view support a tactic of offshore balancing or even restraint, stating that sending external support should be limited and that supporting states should move toward another type of support that can increase the probability of winning. For planning and strategic purposes, the supporting state has a vital interest in evaluating the role that external supports have on conflict outcomes. Consequently, in this article, we are going to do analytical assistance in assessing the effect that external support has on the likelihood of the state and non-state actor winning in a conflict in intrastate conflicts.

Despite the importance of the effect of sending support to debates about military posture and grand strategy, there are few studies to help choose between the contradictory claims. In this article, we proceed first by defining the important terms, then we develop hypotheses on the link between external support and outcome of a conflict, and then, having constructed the necessary research draw conclusions. However, questions about how external support affects the probability of winning also trigger discussions about strategy and the unintentional effects that external support may have on intrastate and interstate conflicts. Also, external support often triggers debates about their costs and the extent to which it will alter the winning probability of the receiver actors.

1- Conflicts and International Relations Theory

As far back as Thucydides’ narrative of the conflicts between Sparta and Athens, the principal source of realist international relations theory is that there is a strong correlation between power and conflict outcomes. Less power leads to losing wars, and more power leads to victory. Therefore, actors pursue to increase their relative power by different means, such as forming alliances or manufacturing or buying armaments. In this view, force is anticipated to have numerous positive consequences results for actors that gain it: it may deter other actors from attacking them, defeat them in conflicts, or cow them into concessions[1]. Realist and motivational theories are the most compelling explanations of the outcomes of conflicts. Both theoretical schools offer valuable insights to clarify the altering pattern of the outcomes of conflicts[2].

a- Realism theory

Realist argues that militarily weak actors cannot prevail in conflicts. In a world where the arbiter of international wars is power, the victory of weak actors is hardly conceivable for Realists. Realists see the power in terms of military capabilities and state that the focal difference between actors is the amount of power they own. For Realists, most actors have some capacity to harm others, and there is no jurisdiction above all that is able of regulating interactions between these actors. Moreover, the outcomes of war mirror the relative power of the actors. Hence, realists do not ask how weak actors win wars, rather, they shift their effort to answer the question of how the balance of power altered to the advantage of the previously weaker actors[3]. When the Balance-of-Power shift for the weak actor, its probability of winning will increase. To do so, weak actors need external support to increase their power capabilities. On the contrary, Motivation theorists have another opinion.

b- Motivation theorists

Non-realist theorists have long argued between the relative power and the capability of states to influence other international actors. The failure of realist arguments to explain how weak actors have won in certain conflicts does not automatically revoke the concept of relative power. Nevertheless, at a minimum, it raises a question over the realist definition of power. The perception of relative power was amended, and instead of the rigid approach of power used by the theorists that emphasized the tangible and material dimensions such as economic strength, manpower, and technological capabilities, researchers presented a softer definition of power that encompassed intangible elements such as motivation, the readiness to sacrifice, national cohesion, and will.

For motivation theorists, what counts during intrastate conflicts is the motivation of the actors. Motivation arises from the relative interests of the actors or from what is at stake for them. Theorists conclude that, when actors recognize that each has a clear understanding of the will and the neutral equilibrium of interests, then one of the actors would have the bargaining advantage[4]. Balance of will scholars drew a link between the outcomes, the motivation of the opponents, and what is at stake in conflicts.

When the Balance of Will and Interests shift for the weak actor, its probability of winning will increase. To do so, weak actors need sometimes external support to increase their Will and Interests capabilities.

2- Characteristics of external supports

By maintaining stationed forces or forward deployed in the supporting state, external support demonstrates national resolve and strengthens alliances. Also, External support enhances the response-ability to contingencies and deter potential adversaries[5]. External supports can take many forms ranging from military activities (e.g., security cooperation) to footprint forces (military assistance, bases, and installations)[6]. External supporters use the forces and footprint activities to project power and influence in the conflict zone. Forces are the size, characteristics, and location of foreign troops involved in the conflict. The footprint is the location of infrastructure and facilities that the foreign troops have access to (e.g., joint security locations) or have direct control (e.g., major operating bases).

a- External support forces.

In this article, we define forces as the external supporting state military personnel, especially those deployed in the intrastate conflict zone. In general, forces are the most flexible tools that the external supporting states have in their arsenal for projecting their presence. However, forces are the most noticeable signs of external support because foreign troops’ presence can be easily witnessed more than agreement or military assistance spending for example[7]. Robert Art sees that forces differ not just in their magnitude but in several features that may ultimately affect the occurrence of conflict, including the length and purpose of their deployment, their location, skills, and capabilities[8]. He claims that whether their presence is permanent or temporary, forces effects directly or indirectly the signal of assurance and commitment it directs to the supporting actors and enemies, and eventually, their conflict performance[9].

External troops’ forces may be located within states, or offshore on an aircraft carrier for example. They are deployed for numerous tasks: some forces are deployed to conduct cooperation and security activities, others are deployed for combat missions in intrastate conflicts, or as part of enduring presence in their allies’ territories. Moreover, each type of military intervention can engage dissimilar numbers of troops, with special skills and capabilities. Lastly, foreign troops may be deployed for a different period. Deployments occurring at bases located abroad can be short, temporary, staffed by a rotating presence (new forces will replace the old one after a certain period), or permanent.

b- External support footprint

External supporter footprint includes supporting states’ infrastructure and facilities, such as military facilities, observatories, naval ports, airfields, and other physical installations, and prepositioned or forward deployed equipment. On one hand, an external supporter’s footprint can act as a sign of commitment to the supporting state, and on the other hand, it enables the supporting state to project influence and power overseas. The forward-deployed military equipment enables the supporting state to have the flexibility to deploy rapidly. Military facilities – ranging from small cooperative security locations (CSLs) to major operation bases – are used to accommodate and support the foreign deployed troops and their equipment. CSLs are installations at which foreign troops’ forces can operate, they can be owned by the local government, or owned by the supporting state, or they can exist as a shared project between the supporting state and the local government. CSLs may be important in allowing access to regions where it can be hard to install foreign troops’ bases. These CSLs also function as a launching point for advanced military operations and enable activities such as intelligence gathering. On the opposite, installations such as naval ports or airfields provide support for the ongoing military operations and can function as touch-down zones for moveable structures, such as naval or aircraft carriers[10].

Joint foreign military actions with the supporting states, for example, security cooperation actions and military assistance, can extend external supporter states’ influence and presence. Security collaboration permits the supporting states to influence directly the expansion of the supported militaries and develop their fighting skills to perform autonomous operations. Moreover, these activities can indirectly reinforce the supporting state’s influence by enlarging the number of allies’ states with whom the supporting countries may militarily collaborate and rely on for support in their intrastate conflicts[11].

Military assistance spending can help supported states build up their independent military capabilities. Nevertheless, the supporting states may also add constraints on this assistance to model the growth of the supported states’ security and military sectors. When these supported states became dependent on the supporting states’ assistance, the supporting states can begin to practice the bargaining tool to accomplish their objectives, such as access for the supporting state on key issues[12].

In short, probably over time, the external supporter states will likely have huge concentrations of their troops in the supported state’s territory. Some supporters tend to deploy smaller militaries for a short duration to help their protégé in their wars; others will deploy large forces in the intrastate conflict zone to support their allies. These tendencies can reveal two details that are central to take into account when evaluating the influence of external support on the intrastate conflict outcome. First, the external supporter can send support to states where conflict is less common, safer, and require less supply than sending support to states where conflict is more predominant. Second, areas less disposed to the conflict to which supports are sent can be safer because of these external supports.

3- External support and actors

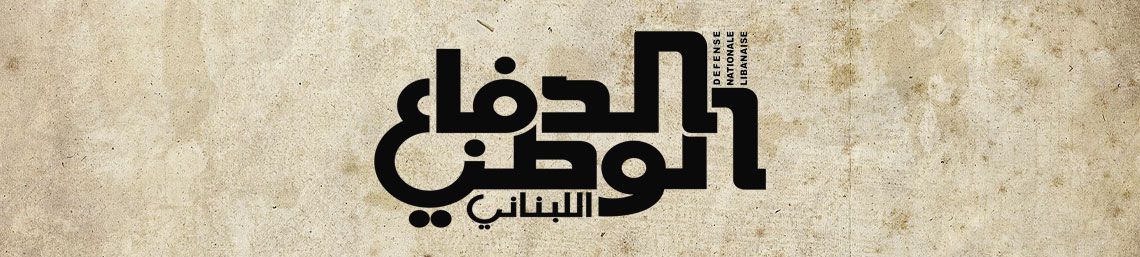

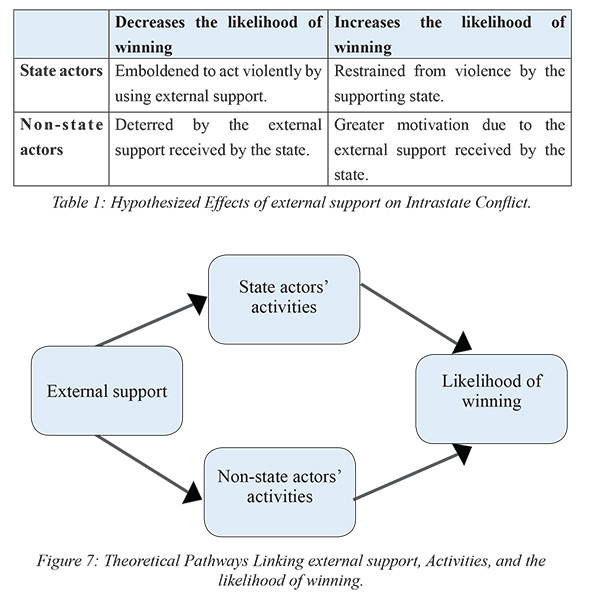

External support can affect positively or negatively the outcome of the state and non-state actors involved in the conflicts. Depending on how these actors handle the support it may increase or decrease their probability of winning. In the following sections, we are going to draw a hypothesized effect of external support on state and non-state actors in intrastate conflicts.

4- State actors

In the absence of popular legitimacy, state actors often practice abuses and repression to maintain and consolidate their political security against the opposition and the local political challenges[13]. States actors may use restrictions, torture, detentions, extrajudicial assassinations, or numerous terror tactics on organizations and movements to change oppositions’ choices about threatening the regime[14]. Such repressions can be widespread or targeted to only selected groups (Egyptian regime bans on the Muslim Brotherhood). Repressions can also be used either preventively or in reply to explicit periods of opposition. Over time, as human rights abuses against the opposition becomes institutionalized and part of everyday life, regular preventive repression allows state actors to rule through terror[15]. In any case, state actors use violence to restrain popular capability to mobilize against the regime and/or to minimize the effect of non-state actors on the local political process[16].

a- External support can restrain state actors from using violence

The proper strategy of external support sent to states can reduce the probability that these state actors resort to violence against their populations. The U.S. for example is obliged to take into consideration the human rights records of the supported states when they want to evaluate the security cooperation.[17] This is clearly mentioned in the Section 502B of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as revised, which reads in part that “no security assistance may be provided to any country the government of which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights unless the President certifies in writing to the Congress that extraordinary circumstances exist warranting provision of such assistance.”[18] Given stated external states policy and some past practices, the supported state actors can fear that if they use repression against their people, this can result in the suspension of external security and military support they receive with the benefits it may provide. Based on his studies of Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela, Laurienti concluded that some state actors have adjusted human rights practices to strategically sustain external support from the United States[19]. In this sense, external support may make state actors less likely to resort to violence.

Proper external support strategy can also lead to security sector reform activities and security cooperation where the supporting states encourage the implementation of institutions and norms that may restrain the incumbent regimes from using unnecessary violence. In this way, external support can help in the improvement of long-term security organizations that value human rights[20].

b- External support can embolden state actors to use violence

Sometimes, increased external support increases the violence used by state actors against non-state actors in intrastate conflicts. As an example, between 1988 and 2005, the U.S. military support to the Colombian state was linked with a significant upsurge in the regime attacks on the non-state actors and on the civilians and was linked with increased violence of the rebel forces[21]. Increased external support may increase the violence of some partner states. External support can enhance the incumbent government’s security against the outside menace, releasing up resources to be used for local oppression. Furthermore, external support that was intended to shield the supported states’ security against external threats can involuntarily provide tools for the supported state actors to turn toward repression[22].

Likewise, increased external support provides state actors with an important outside source of nontaxable incomes that can lead to an increase in the risk of government human rights abuses and violence[23]. As states’ nontaxable incomes increase, there is a fewer economic motivation for the state actor to endorse economic and political productivity by its public for constant income. Economic security offered by the external supporter states combined with guaranteed external security, separate furthers the population from their incumbent regimes and reduce the costs related to violence and human rights abuses committed by the regime.

5- Non-state actors

External support can affect the probability that non-state actors defy the incumbent regime. Existing scholarship suggests that external support can deter or intensify grievances, providing non-state actors more incentive to raise arms. These paths happen with blended empirical support, which can reflect globally the variety of opposition incentives.

a- External support can deter non-state actors.

As previously discussed, by directly supporting the incumbent countries, the supporting state improves the ability of the government to put down dissent and rebellion. For their part, opposition groups and potential rebels are strategic non-state actors who frequently consider the feasibility of their operations against the state. In other words, when choosing whether to challenge the state, non-state actors analyze their chances of survival or success. As external support increases the ability of partner states to fight the rebellion, non-state actors can be deterred from rising arms or initiating a nonviolent operation against the state[24]. U.S. presence in the supporting states is one example.

The main purpose of the United States presence in Afghanistan focused on extending and supporting the competencies of the Afghan armed forces against a determined insurrection. Equally, the United States security support to Egypt and Pakistan was principally centered on improving their capabilities to deter anti-regime radical groups, ranging from militant to political elements, which can eventually menace the U.S. regional interests.

b- External Support can increase non-state actors’ motivation

External support carries a menace of enflaming popular sentiments against state actors involved in the conflicts and provoking greater anti-state movements. The local populace may see external support as a soft occupation, leading to nationalist sentiments against foreign involvement or intervention of other states in domestic politics. External support can also be linked with other undesirable consequences, such as disturbances to local markets, and increased demand for illegal activities that can divide more the local population. Examples where such sentiments afflicted external supporters in local politics happen in Afghanistan where they rally militant support against the Russian troops, and in Iraq and Afghanistan with the U.S. troops. In essence, several scholars affirm that external support often helps foment popular opposition that external support is designed to deter.

Similarly, external support may indirectly increase opposition movements by increasing and intensify the conflict between partner states. Researchers have noted that the use of excessive oppression to suppress the anti-state movement, often ends by boosting the opposition[25]. External support often diminishes popular support for the state and increases popular anti-government sentiments.

c- External support can reduce non-state actors’ grievances

Through economic development, external support may decrease indirectly the jeopardy of anti-regime campaigns. Political and economic grievances resulting from economic inequality most often led to either nonviolent or violent challenges to states[26]. Some scholars have found that external support is linked to a certain extent to accelerated social and economic development, because of larger access to the supporter state investment and trade. Also, increased external support for partner states often decreases some of its security burdens, allowing partner states to reinvest capitals reserved for security into welfare or infrastructure developments. In the end, this may lead to raising the political support via economic expansions[27]. In correlation to this, Djibouti and Ethiopia are two examples. These two states were the fastest-growing economies in sub-Saharan Africa because they were the major hosts of the U.S. military presence[28].

New economic opportunities created by increased external support, may decrease economic grievances, and minimize the need of the formerly angry portions of the population to rally against the state. Moreover, improving the economic situation can minimize the recruiting abilities of terrorist and militant groups, as fewer people are drifted toward militarized armed conflicts through anti-regime grievances or economic needs. In sum, these additional benefits of external support can indirectly help in consolidating the long-term stability of the supported countries against fierce hostility[29].

d- External support and Levels of State Repression

The level of state repression can also be affected by external support in several possible ways. By helping in security sector reforms the supporting states better restrain partners, and thus the external supports they send can lead to less state repression. Alternatively, external support could persuade an incumbent government that the external supporting state commitment is robust and make him insensitive to the level of state repression. External support also can give the supporting states extra resources that could be redirected toward local repression. Still, a preliminary review of relevant cases illustrates how external support can contribute indirectly to state repression. Turkey is an example of this scenario.

Since the post-WWII period, Turkey acquired high levels of support from the government of the United States. Beginning in the 1980s, during the counterinsurgency operation carried out by Turkey against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the U.S. State Department reported multiple attacks executed by the Turkish state on civilians, as well as disappearances and torture. The U.S. support could not leverage the Turkish government to restrain its actions against the PKK[30].

e- External support and Anti-Regime Activities

As previously discussed, external support may deter non-state actors from starting an anti-government campaign against the state. However, this support may sometimes initiate further anti-government movements by producing new protests against the current government. Non-state actors can also be emboldened to start new operations, considering that external support will let the supporting state stop the incumbent regime from employing excess aggression to suppress hostility.

Now that we have linked external support with actors’ activities, in the following section, we will link external support to conflicts.

7- How external support may influence interstate conflict behavior

Supporting states usually send support overseas to help their allies in their conflicts. Policymakers usually contend that the strength of the external supporter and their local presence in strategic areas all serve in helping and deterring assaults against their partners. Also, using a wide range of economic and political incentives these supporting states can participate in international coalitions to influence other states’ actions and foreign policy choices. Though, while these assumptions are broadly acknowledged within the strategy community, limited studies explore whether there is a logical confirmation for these assumptions.

Through multiple paths, external supports affect the outcome of an interstate conflict on the geopolitical level. External supports may affect adversaries and partners’ motivations to use militarized operations, such as unilateral attacks, threats, or military mobilizations. In turn, the correlation between these activities and responses affects the probability that these militarized operations will increase the fighting capability of all the actors involved in these intrastate wars. Because we cannot separate intrastate conflicts from the regional and geopolitical content, external supports in intrastate conflicts may also influence interstate conflict behavior.

To respond to crises and to deter interstate conflicts, states often deploy forces overseas. The overall strength of the supporting state armed forces in vital areas is used to deter attacks against their partners. Furthermore, through participation in international coalitions and a range of economic and political incentives, powerful supporting states may affect other countries’ foreign policy choices[31].

In addition to the external support have on the geopolitical level, external support can change the strategic and tactical calculations of important regional and local political state and non-state actors, such as incumbent regimes and hostile and opposition groups. The interactions and behavior between them can also affect the outcome winning probability in interstate conflict. External support may increase external state influence on partner state and non-state actors. Moreover, if the state’s security is strengthened by external support, non-state actors may be deterred from challenging incumbent regimes. Alternatively, external support improves the security of state actors against external threats and lets them use their resources in internal repression.

Concluding, a consistent association exists between external support and interstate conflict outcome. As in this section, we developed hypotheses regarding the effects of external support and interstate conflict, in the following sections, we will draw an association between external support and intrastate conflict outcome and develop hypotheses on the linkage between these two entities.

8- How external support may influence intrastate conflict behavior

Historically, concerns about deterring the adversary in interstate conflicts mainly drove external support decisions. Nevertheless, since the end of the Cold War, external support has increasingly focused on helping the supported states against internal non-state actors. Supporters’ states centering decisions mainly focused on addressing the instability and fragility of the supporting state in intrastate conflicts. Even during the period when most of the external state’s policy was generally determined by concerns about interstate conflict, external supports have had secondary or involuntary consequences on the outcome of intrastate wars. Just like external support can affect the behavior and the outcome of interstate conflict; it may also change the strategic calculations of the warring actors, including opposition groups and incumbent governments. In turn, their interactions and behavior may affect the probability of the winning outcome in intrastate conflict.

From the result of the study of the interaction that exists between multiple non-state actors within a state, Stephan and al. affirmed that intrastate conflicts are a complicated process. They concluded that these groups may include the opposition movements, labor or student groups, ethnic groups, and the incumbent regime[32]. Conditioning by these numerous interactions, intrastate conflict might manifest in many ways.

Strategists, analysts, and scholars often are alarmed with the occurrence of intrastate conflicts, where incumbent regimes have contended against militant or armed groups for controlling the state. Often, intrastate conflicts increase the violence within the border of a country and increase the risk that the conflict will extend to the bordering countries and destabilize the whole region[33]. To the highest degree, extensive and prolonged intrastate conflicts may lead to a total government collapse, or it can increase the risk that the state becomes an open host for terrorist groups or subject to rebel rule[34]. For example, in Somalia, several years of civil war eventually led to a total collapse of the country, which then led to a military intervention by the neighboring Ethiopian state to enclose the hostilities.

As the escalation from intrastate intensity conflicts may result in full-scale interstate hostilities, external supports are often linked to the intensity of intrastate conflicts. For example, non-state actors may initiate their disagreement from political opposition activities and turn to violence in response to government abuses or when excluded by force from the domestic political process. Beyond this interaction, states may resort to abuses and repression to oppress local opposition activities, reducing or increasing the afflux of external support to the warring actors. In 2012, the Syrian war highlighted these mechanisms.

As one episode in the wider Arab Spring that starter in 2011, the Syrian war started as a sequence of nonviolent manifestations, where the protestors asked for economic and democratic reforms. The Syrian government replied with brutal police repressions and a militarized response. In turn, protestors’ demands converted to become more general, and their strategies became more and more brutal. This spiral of brutality between the Syrian regime and the opposition finally expanded to the point of armed rebellion, preparing the arena for the afflux of external support[35].

As the Syrian conflict reveals, processes of external support and intrastate conflict are often cyclical and interconnected. Academic examined how external support can mark the tactical interaction between states and non-state actors, and showed how external support may affect the risk of intrastate conflict. Moreover, they showed how external support can affect and mark each of the two warring actors: the state actors (incumbent governments), and the non-state actors (opposition groups).

External support may increase influence on the supported states to advance their conditions within their frontiers. Moreover, when the state’s security apparatus is reinforced by external supports this may potentially deter opposition groups from challenging or testing the incumbent regimes. Feeling secure through external support, states may increase their abuses to punish the opposition. However, external support may also ignite existing objections against the regime, and states.

Increased opposition grievances and state repression can make intrastate conflicts more probable to initiate. Cycles of disagreement and state violence can spiral to a full intrastate conflict, and later lead to an afflux of external support and then it might escalate to interstate war. Also, the association between external support and intrastate conflict varies over time. In the Cold War era and the wake of the post-Cold War, external support was associated with larger levels of state repression, and with increased levels of armed conflict and anti-regime activity in intrastate wars. Therefore, to evaluate the effects of external support on intrastate conflicts, we must consider the responses to external support by state and non-state actors.

This article can offer guidelines for geopolitical and strategic planners and policymakers considering future sending of external support: first, external support may be an effective tool in deterring non-state actors or on the opposite can give greater motivation to non-state actors in intrastate wars. When external support deters the non-state actors, this will increase the likelihood of the state winning. On the contrary, because sometimes external support that was projected to deter can also inflame more militarized actions, external support may give greater motivation to non-state actors. These activities will increase the fighting capability of the non-sate actors and though increase their likelihood to win. Second, external support emboldens the state actors to embolden or on the opposite restrain state actors to use violence. Table 1 below summarizes these hypotheses.

Conclusion

In this article, we evaluated the relationship between external support, actors, and intrastate conflict. External support can have important effects on intrastate outcomes, influencing state actors, and non-state actors alike. To capture these possible effects, we considered many divergent outcome measures associated with intrastate conflict and found that external support has a significant effect on conflict outcomes. Furthermore, external support can affect the government incentives in pursuing their repression and the non-state actors to initiate anti-state activities. These actions and reactions between these adversaries’ actors may affect intrastate conflict outcomes. External support can lead to state repression and thus anti-state campaigns. Also, both state repression and anti-state movements have intermediate effects on the outcome of wars. For non-state actors, such anti-state campaigns aim to make some significant transformation in the state’s political atmosphere, like overthrowing the government and changing the political power, or forcing better rights and independence for certain non-state actors[36].

In intrastate conflicts, external support often varies in intensity. For example, the Syrian conflict has developed to include multiple non-state actors and became a geopolitical flashpoint where many external supporters get involved at different levels. Intrastate wars are often linked to external support and may signal the hazard of larger interstate conflict. In sum, external support can increase the risk that intrastate conflicts intensify to full-scale interstate conflict between the supporting states.

Bibliography

- Abboud, Samer N. Syria: Hot Spots in Global Politics. Place of publication not identified: POLITY Press, 2018.

- Arreguín-Toft, Ivan. How the Weak Win Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Art, Robert J. “A Defensible Defense: America's Grand Strategy after the Cold War.” International Security 15, no. 4 (1991): 5-53. Accessed April 23, 2020. doi:10.2307/2539010.

- Bell, Sam R., K. Chad Clay, and Carla Martinez Machain. “The Effect of US Troop Deployments on Human Rights.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 10 (2016): 2020–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716632300.

- Blanton, Shannon Lindsey. “Instruments of Security or Tools of Repression? Arms Imports and Human Rights Conditions in Developing Countries.” Journal of Peace Research 36, no. 2 (1999): 233-44. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/424671.

- Buhaug, Halvard, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. “Contagion or Confusion? Why Conflicts Cluster in Space.” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2008): 215-33. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/29734233.

- Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563-95. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3488799.

- Collier, Paul, Anke Hoeffler, and Dominic Rohner. “Beyond Greed and Grievance: Feasibility and Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 61, no. 1 (2009): 1-27. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/25167719.

- Davenport, Christian, and David A. Armstrong. “Democracy and the Violation of Human Rights: A Statistical Analysis from 1976 to 1996.” American Journal of Political Science 48, no. 3 (2004): 538-54. Accessed April 24, 2020. doi:10.2307/1519915.

- Davenport, Christian. “State Repression and the Tyrannical Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 44, no. 4 (2007): 485-504. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/27640542.

- Davenport, Christian. State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- DeMeritt, Jacqueline H.R., and Joseph K Young. “A Political Economy of Human Rights: Oil, Natural Gas, and State Incentives to Repress.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30, no. 2 (2013): 99-120. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/26275314.

- Dube, Oeindrila, and Suresh Naidu. “Bases, Bullets, and Ballots: The Effect of US Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia.” The Journal of Politics 77, no.1 (2015): 249-67. Accessed April 28, 2020. doi:10.1086/679021.

- Forsythe, David P. “Congress and Human Rights in U. S. Foreign Policy: The Fate of General Legislation.” Human Rights Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1987): 382-404. Accessed April 27, 2020. doi:10.2307/761880.

- Joint Publication 1-02, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, JP 1-02, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, 2010. Amended through 15 February 2016.

- Jones, Seth G., Olga Oliker, Peter Chalk, C. Christine Fair, Rollie Lal, and James Dobbins. “Conclusion.” In Securing Tyrants or Fostering Reform? U.S. Internal Security Assistance to Repressive and Transitioning Regimes, 161-74. Santa Monica, CA; Arlington, VA; Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Corporation, 2006. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg550osi.15.

- Kugler, Richard. Changes Ahead, Future Directions for the U.S. Overseas Military Presence. United States: Rand Corp santa monica ca, 1998.

- Laurienti, Jerry M. The U.S. Military and Human Rights Promotion: Lessons from Latin America. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2007.

- McNerney, Michael J. Assessing Security Cooperation as a Preventive Tool. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2014.

- Merom, Gil. How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Mills, Patrick, Adam Grissom, Jennifer Kavanagh, Leila Mahnad, and Stephen M. Worman. “The Costs of Commitment: Cost Analysis of Overseas Air Force Basing.” In A Cost Analysis of the U.S. Air Force Overseas Posture: Informing Strategic Choices, 1-30. RAND Corporation, 2013. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt5hhtfk.9.

- Piazza, James A. “Incubators of Terror: Do Failed and Failing States Promote Transnational Terrorism?” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 3 (2008): 469 88. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/29734247.

- Poe, Steven C., and James Meernik. “US Military Aid in the 1980s: A Global Analysis.” Journal of Peace Research 32, no. 4 (1995): 399-411. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/425611.

- Regan, Patrick M., and Errol A. Henderson. “Democracy, Threats and Political Repression in Developing Countries: Are Democracies Internally Less Violent?” Third World Quarterly 23, no. 1 (2002): 119-36. Accessed April 24, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3993579.

- Stephan, Maria J., and Erica Chenoweth. “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.” International Security 33, no. 1 (2008): 7-44. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/40207100.

- The National Military Strategy of the United States of America 2015: the United States Military’s Contribution to National Security. (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff), 2015, 2.

- The World Bank, “World Development Indicators,” 2016.

- Tilly, Charles. From Mobilization to Revolution. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

- Watts, Stephen, Olga Oliker, Stacie L. Pettyjohn, Caroline Baxter, Michael J.McNerney, Derek Eaton, Patrick Mills, Stephen M. Worman, and Richard R.Brennan, Jr. “Increasing the Effectiveness of Army Presence,” Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, unpublished manuscript.

- Weapons transfers and violations of the laws of war in Turkey.” Turkey. Accessed April 30, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/reports/1995/Turkey.htm.

[1]- Arreguín-Toft, How the Weak Win Wars, 2.

[2]- Gil Merom, How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 5.

[3]- Merom, How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam, 6.

[4]- Merom, How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam, 11.

[5]- Joint Publication 1-02, Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, JP 1-02, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, 2010 (amended through 15 February 2016).

[6]- Stephen Watts, Olga Oliker, Stacie L. Pettyjohn, Caroline Baxter, Michael J. McNerney, Derek Eaton, Patrick Mills, Stephen M. Worman, and Richard R. Brennan, Jr., “Increasing the Effectiveness of Army Presence,” Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, unpublished manuscript.

[7]- Robert J. Art, “A Defensible Defense: America’s Grand Strategy after the Cold War.” International Security 15, no. 4 (1991): 5-53. Accessed April 23, 2020. doi:10.2307/2539010.

[8]- Art, “A Defensible Defense: America’s Grand Strategy after the Cold War,” 5-53.

[9]- Art, “A Defensible Defense: America’s Grand Strategy after the Cold War,” 5-53.

[10]- Patrick Mills, Adam Grissom, Jennifer Kavanagh, Leila Mahnad, and Stephen M. Worman. “The Costs of Commitment: Cost Analysis of Overseas Air Force Basing.” In A Cost Analysis of the U.S. Air Force Overseas Posture: Informing Strategic Choices, 1-30. RAND Corporation, 2013. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt5hhtfk.9.

[11]- Richard Kugler, Changes Ahead, Future Directions for the U.S. Overseas Military Presence. (United States: Rand Corp santa monica ca, 1998), 12.

[12]- Steven C. Poe, and James Meernik, “US Military Aid in the 1980s: A Global Analysis.” Journal of Peace Research 32, no. 4 (1995): 399-411. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/425611.

[13]- Christian Davenport, and David A. Armstrong, “Democracy and the Violation of Human Rights: A Statistical Analysis from 1976 to 1996.” American Journal of Political Science 48, no. 3 (2004): 538-54. Accessed April 24, 2020. doi:10.2307/1519915.

[14]- Christian Davenport, State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 1-32.

[15]- Patrick M. Regan, and Errol A. Henderson, “Democracy, Threats and Political Repression in Developing Countries: Are Democracies Internally Less Violent?” Third World Quarterly 23, no. 1 (2002): 119-36. Accessed April 24, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3993579.

[16]- Charles Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998), 1-11.

[17]- David P. Forsythe, “Congress and Human Rights in U. S. Foreign Policy: The Fate of General Legislation.” Human Rights Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1987): 382-404. Accessed April 27, 2020. doi:10.2307/761880.

[18]- Forsythe, “Congress and Human Rights in U. S. Foreign Policy: The Fate of General Legislation,” 382-404.

[19]- Jerry M. Laurienti, The U.S. Military and Human Rights Promotion: Lessons from Latin America. (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2007), 1-23.

[20]- Seth G. Jones, Olga Oliker, Peter Chalk, C. Christine Fair, Rollie Lal, and James Dobbins, “Conclusion.” In Securing Tyrants or Fostering Reform? U.S. Internal Security Assistance to Repressive and Transitioning Regimes, 161-74. Santa Monica, CA; Arlington, VA; Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Corporation, 2006. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg550osi.15.

[21]- Oeindrila Dube, and Suresh Naidu, “Bases, Bullets, and Ballots: The Effect of US Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia.” The Journal of Politics 77, no. 1 (2015): 249-67. Accessed April 28, 2020. doi:10.1086/679021.

[22]- Shannon Lindsey Blanton, “Instruments of Security or Tools of Repression? Arms Imports and Human Rights Conditions in Developing Countries.” Journal of Peace Research 36, no. 2 (1999): 233-44. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/424671.

[23]- Jacqueline H.R. DeMeritt, and Joseph K Young, “A Political Economy of Human Rights: Oil, Natural Gas, and State Incentives to Repress.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30, no. 2 (2013): 99-120. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/26275314.

[24]- Paul Collier, Anke Hoeffler, and Dominic Rohner. “Beyond Greed and Grievance: Feasibility and Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 61, no. 1 (2009): 1-27. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/25167719.

[25]- Christian Davenport, “State Repression and the Tyrannical Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 44, no. 4 (2007): 485-504. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/27640542.

[26]- Paul Collier, and Anke Hoeffler, “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563-95. Accessed April 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3488799.

[27]- Sam R. Bell, K. Chad Clay, and Carla Martinez Machain, “The Effect of US Troop Deployments on Human Rights.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 10 (2016): 2020–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716632300.

[28]- The World Bank, “World Development Indicators,” 2016.

[29]- Michael J. McNerney, Assessing Security Cooperation as a Preventive Tool. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2014).

[30]- “Weapons transfers and violations of the laws of war in Turkey.” Turkey. Accessed April 30, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/reports/1995/Turkey.htm.

[31]- The National Military Strategy of the United States of America 2015: the United States Military’s Contribution to National Security. (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff), 2015, 2.

[32]- Maria J. Stephan, and Erica Chenoweth, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.” International Security 33, no. 1 (2008): 7-44. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/40207100.

[33]- Halvard Buhaug, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Contagion or Confusion? Why Conflicts Cluster in Space.” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 2 (2008): 215-33. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/29734233.

[34]- James A. Piazza, “Incubators of Terror: Do Failed and Failing States Promote Transnational Terrorism?” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 3 (2008): 469-88. Accessed April 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/29734247.

[35]- Samer Abboud, Syria: Hot Spots in Global Politics. (Place of publication not identified: POLITY Press, 2018), 59-61.

[36]- Sambanis, 2004; Kalyvas, 2006.

الدعم الخارجي في النزاعات

العقيد المهندس جهاد الخوري

من إحدى الفرضيات التي تحكم القتال بين الجهات الحكومية وغير الحكومية في النزاعات داخل الدول هي بدء الصراعات من قبل الجهات الحكومية بفائضٍ من القوة على الجهات غير الحكومية؛ وفي المقابل، تتمتع الجهات غير الحكومية بفائضٍ من الاستعلام على الجهات الحكومية. ومن الفرضيات الأخرى التي تحكم الحروب بشكلٍ عام هي ترابط القوة والاستعلام بشكلٍ إيجابي. وهذا يعني أنه كلما زادت قوة الطرف، كلما قلّت إمكانية تخفّيه وكثرت المعلومات حوله.

هناك نقاش مستمر بين قادة القرار الاستراتيجيين حول تأثير إرسال الدعم الخارجي في النزاعات داخل الدول حول العالم. بحسب إحدى وجهات النظر، قد يعتقد المرء أن الدعم الخارجي يجب أن يساعد الجهات الفاعلة المستقبلة لهذا الدعم في قتالها، ومن شأنه أن يردع الخصوم، وأن يجعل من السهل على هؤلاء الفاعلين تحقيق أهدافهم باستخدامه. ويؤيّد المدافعون عن هذا الطرح التوسع والاستمرار في إرسال الدعم الخارجي في النزاعات داخل الدول. وترى وجهة نظر أخرى أن إرسال الدعم سيؤدي إلى نتائج عكسية وسيقلّل من احتمالية الفوز في الصراع ومن شأنه استفزاز الخصوم ورفع الروح الوطنية.

كذلك، يؤيّد المدافعون عن هذا الطرح تكتيك الموازنة الخارجية أو حتى ضبط النفس، مشيرين إلى أن إرسال الدعم الخارجي يجب أن يكون محدودًا والدول الداعمة يجب أن تتحرك نحو نوع آخر من الدعم الذي يمكن أن يزيد من احتمالية الفوز. ولأغراضٍ تخطيطية واستراتيجية، فإن الدولة الداعمة لها مصلحة حيوية في تقييم الدور الذي يؤديه الدعم في نتائج الصراع. وبالتالي، في هذه المقالة، سنقوم بتقييم تأثير هذا الدعم في احتمالية فوز الدولة والجهات غير الحكومية في الصراع داخل الدول.

على الرغم من أهمية تأثير إرسال الدعم في الموقف العسكري وعلى الاستراتيجية الكبرى، هناك القليل من الدراسات التي تساعد في الاختيار بين الادعاءات المتناقضة. في هذه المقالة، ننتقل أولًا من تحديد المصطلحات المهمة، ثم نقوم بتطوير الفرضيات حول الارتباط بين الدعم الخارجي ونتائج الصراعات لنبني الاستنتاجات اللازمة للبحث. ومع ذلك، فإن الأسئلة حول كيفية تأثيره في احتمالية الفوز تثير مناقشات حول الاستراتيجية والتأثيرات غير المقصودة أيضًا التي قد يحدثها هذا الدعم على النزاعات داخل الدول وفيما بينها. كذلك، غالبًا ما يثير تساؤلات حول تكاليفه والمدى الذي سيغيّر فيه احتمال فوز الجهات المستفيدة.