- En

- Fr

- عربي

The geopolitics of Poland: A regional power in the making

Introduction

Geopolitics is about perspective and interaction among states and empires in a particular geographical setting. It is the influence of geography upon politics.

It is about trying to distinguish, through the lens of power and geography, things that are perpetual, ephemeral and of a long duration.

Nicholas Spykman, the politician and founder of the classical realist school, said: "ministers come and go, even dictators die, but mountain ranges stand unperturbed".

In a nutshell, geopolitics is a field that studies the relationship between space and force along the lines of history. This field examines the origins, development, and causes of the rise and collapse of powers in time and space.

But the questions that come into play are numerous: How does geographic space influence the formulation of goals and interests of international players - states and unions - and what are the causes for the rise and fall of states?

To address this subject with a strategic approach, let’s take Poland as an example.

For Poland, geopolitics is an existential threat. Losing on its fronts can lead to an all-out invasion and triggers a national catastrophe. For other countries, geopolitics is not as existential as an issue. Sometimes, it doesn’t really matter whether you win or lose.

When you get to hear Chopin’s Polonaise and Revolutionary Etude, you can feel a clear expression of rage, hope and despair. These feelings were a clear condemnation for Russians and French, who helped to crush the uprising that took place in Warsaw in November 1831. As a result, the lack of trust and the reluctance to ask for foreign aids stayed in Poland’s conscience to this day.

Taking a closer look into Polish history, you will always get the sense that disaster is lurking just around the corner. Therefore, Poland’s national strategy is always designed with an underlying sense of fear and desperation. But as a beacon of hope, massive political and economic transformations are sweeping Poland. The Polish economy performed painful reforms to emerge from decades of state control to morph into more privatized industries and market competition.

Poland will try to benefit from all the opportunities while trying to mitigate the threats along the way. It has a significant potential to grow into a wealthy and stable nation.

Will Poland be a regional superpower, or will it be condemned to geography as a land of war?

Different factors come into consideration:

1) Geographical location;

2) Poland’s history of tragedy and greatness rooted in its culture and

3) Its economy, which can become Europe’s new growth engine.

We will try to approach these three factors in order to have a clearer view of the past, an understanding of the present and a glimpse of the future.

1- Geography’s curse

Throughout history, geography has been the stage on which nations and empires have collided. The geography of a state - its position in a geographical region and in the world as a whole, presents opportunities to, and imposes limitations on, the state.

It is established that understanding geography is essential for geopolitical analysis where it is the most crucial factor in international politics because of its permanent factor.

For this reason, geography imposes on states’ leaders or rulers well-defined political perspectives and thereby, affects their decision-making in matters of foreign policy[1].

Poland in perspective:

It’s rarely an article on geopolitics had been written without the direct mention of the MacKinder’s[2] theory who suggested in 1904 that the control of Eastern Europe was vital to control the world. He postulated the following which became known as the MacKinder Heartland Theory:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland?

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island?

Who rules the World-Island commands the world?

According to MacKinder, the “heartland” is also referred to as the “pivot area” and it is designated as the core of Eurasia, and he considered all of Europe and Asia as the World-Island. He argued that the Eurasian landmass should never be dominated by a single power or a coalition of powers.

Outside of the Pivot area is the marginal or inner crescent, which Spykman later labeled as "The Rimland", which is part continental and part oceanic and beyond that is the outer crescent, which is entirely oceanic. To the south, east, and west of the heartland lie what Mackinder called the “marginal regions” of the inner crescent.

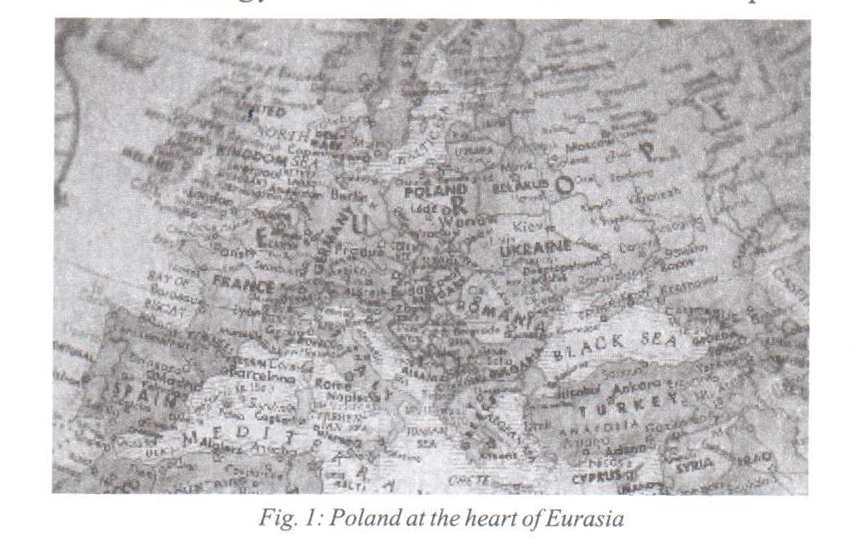

It is relatively easy to spot Poland’s position as the center of the Eurasian landmass (Figure 1). This position was the root cause of Poland’s tragedy for centuries.

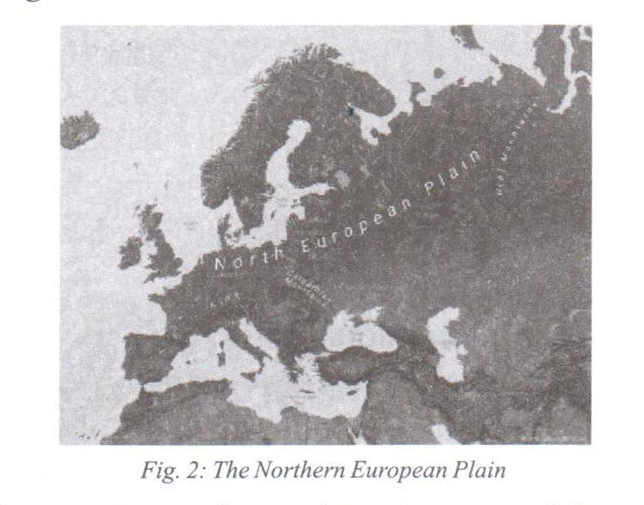

The national strategy of Poland revolves around the preservation

of its national identity and independence: It is situated on the flat, open plains of northern Europe, with no natural boundaries separating it from Germany to the west and Russia to the east, Poland was often torn between the two (Figure 2).

Throughout the years, Poland's existence was heavily susceptible to the moves of major Eurasian powers: To the east, Russia (a massive empire by 1830), to the west, the Prussians (Germany after 1871) and to the south, the Hapsburg Empire (until 1918). This has led Poland to be the major theater of the bulk of European conflicts.

To note, Poland became the subject of various attempts by its adjacent neighbors, such as the Third Reich from the West, Russia and the Soviet Union from the East, Sweden (in the 17th and 18th centuries) from the North, and finally Turkey (in the 16th and 17th centuries) from the South.

Being besieged with these powerful neighbors, no amount of courage or wisdom could survive forces as massive as this.

Therefore, Poland has known a chaotic history with fluctuation between independence and regional dominance, surviving only in language and memory before emerging as an independent country once again [3].

Evidently, the statement that Poland has a terrible geographical position is a truism. To this day, the ultimate fear for Poland has always been to be simultaneously attacked by both Russia and Germany.

Politics in perspective:

The delicate position of Poland forced it to deal with two assertive neighbors. On one hand, the Russians were increasingly afraid of European and American help to Europe in general and to Eastern Europe in particular. This aid is perceived (to this day) as undermining Russia’s economic viability and saw NATO’s expansion as a strategy to strangle Russia[4] .

On the other hand, the Germans saw their expansion west as a vital move to ensure their “Lebensraum”, or the vital space in which Germany can prosper.

This is the heart of Poland's strategic problem. As an independent country in the 20th century, Poland sought multilateral alliances to protect itself from Russia and Germany - among these alliances was the Intermarium.

The idea of the Intermarium dates back to the post World War I period. After the Soviet capitulation to the Germans in 1917 and the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, a large deal of territory was ceded to Germany including Ukraine. After Germany lost the war, the Soviets tried to regain what they have given in the Brest-Litovsk treaty[5]. In 1920, a climactic battle took place in Warsaw, when an army led by Polish Gen. Jozef Pilsudski blocked a Soviet invasion.

Pilsudski was a Polish nationalist with a geopolitical vision who understood that Russia's defeat by Germany was the first step to an independent Poland. He believed that Polish domination of Ukraine would guarantee Poland's freedom and independence after the defeat of Germany. His attempt to ally with Ukraine failed as Russians defeated the Ukrainians and turned on Poland but Pilsudski defeated them[6].

With his ingenuity, Pilsudski tried to take advantage of the weakness of Germany and Russia who were both in shambles. This situation did not last for long. Pilsudski thought to take advantage of the moment and created an alliance to save the region. His vision was something called the Intermarium, which was an alliance of the nations between the seas built around Poland and including Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Finland and the Baltic states. This never came to materialize; otherwise, we would have seen history written in a very different way: World War II might have prevented or played out in a very different way.

For achieving his goal, he needed two preconditions: 1) complete military defeat of Russia and 2) deep co-operation of the nations involved in the project .

Neither option became a reality.

Pilsudski's Intermarium makes a kind of logical sense: the concept promoted calling for an alignment comprising Central European countries from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea to resist Germany and Russia.

Needless to say, the Intermarium was censored by the Soviet Union and then Russia in the post-Cold War era. It existed only as a mere slogan, especially for the right-wing Poles.

Then, in 2015, a new idea emerged. The so-called Three Seas Initiative appeared and was followed by two summits (one in Dubrovnik in 2016 and the other in Warsaw in 2017). With the creation of the Three Seas strategy, the world would have witnessed a shift from a passive stance of the Eastern European countries awaiting Russian interferences to a more active one trying to integrate the Balkans into their alliance.

It was a revival of the Intermarium Strategy and by it the old Polish strategies began to re-emerge. We saw the old existential questions concerning Poland reformulated: Does Poland still aspire to play the role of regional leader? Or it just wants to protect itself while being at a distance from other powers?

The rationale behind the creation of the Intermarium (or the Three Seas Strategy) is the assumption that Europe will not protect its eastern borders against a Russian threat. Therefore, Eastern European countries are left to their own capabilities and a distant alliance with the United States. Otherwise, if they acted separately, Russia has the ability to crush them. If this alliance has the chance to be brought to life, it must include Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan in order to contain most of European Russia.

Strategic solution

Poland’s first strategic solution should be establishing close ties with NATO and the European Union to counter these challenges. But a question emerges from this predicament: to what extent can Poland rely on the viability of NATO as a military force? The answer is less than clear and the future of the European Union is clouded, as Frans Timmermans, the deputy leader of the European Commission once said: “there are two kinds of countries in Europe, small ones, and those who don’t know yet that they are small”.

The problem with NATO alliances is one of a habit and convenience. NATO has become nowadays, selective in its engagements. Pre 1991, NATO had a clear purpose of deterring Russia from invading Europe. Today this clear purpose does not exist anymore and participation in wars is becoming elective. To be more precise, participation can be broad but militarily insignificant and participation in conflict is not automatic but optional. Therefore, NATO is no longer an alliance, as an alliance requires mutual interests and support.

Before laying out the clear Polish strategy capable of shifting Poland’s curse of geography from a liability to an asset, we will take a close look at the country callousness of history.

2- Ruthlessness of history

Poland has been an independent kingdom for the past 800 years before the nineteenth century.

But in 1795, Poland was wiped off the map of Europe. It was absorbed by three great neighboring powers: the Prussian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires. This situation lasted until 1918.

It must be highlighted that Polish history was not always about the nobility of failure. Poland was one of Europe’s greatest powers - Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - prior the emergence of the Russian empire, or the Hapsburgs organization of southeastern Europe and the rise of Prussia. This alliance forged in the 17th century encompassed the entire region from the Baltic Sea to approximately the Black Sea, from western Ukraine into deep Germanic regions.

This part of history has been considered as Poland’s greatest time. It is not clear that they fully appreciate why they were once great, why the greatness was taken away from them or their resurrection is not unthinkable. The Poles know that they once dominated the North European Plain and they are convinced that it will never happen again.

By 1795, it had ceased to exist as an independent country, divided among three emerging powers: Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

It did not regain independence until after World War I when the Treaty of Versailles created it in 1919. It spent few short years as a democracy before proving ungovernable and succumbing to dictatorship.

At the beginning of World War II in 1939, Poland was once again conquered and divided by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Over the next six years, Poland found itself at the center of the European battlefields. Its statehood was formalized in 1945, but it was dominated by the Soviets until 1989.

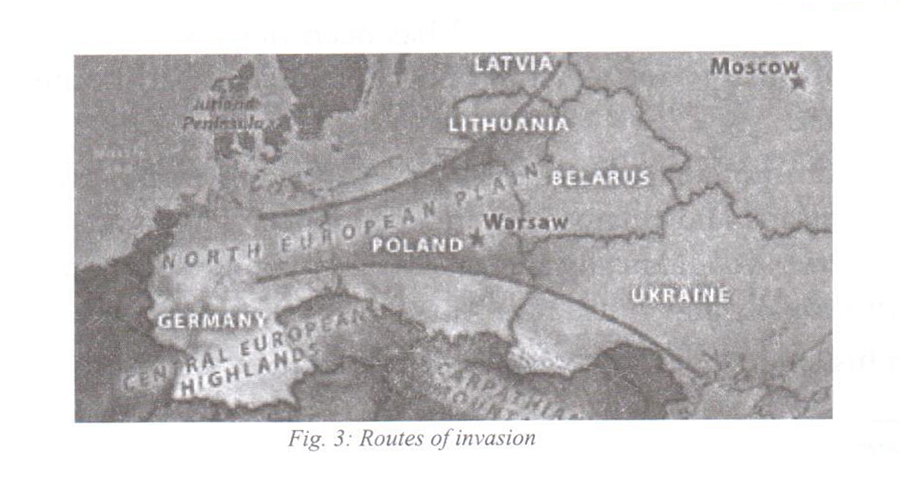

This country has endured the atrocities of World War II with

more than five million Poles dead and much more injured. The Nazis and the Soviets wiped out the majority of Poland’s intelligentsia and clergy. Unfortunately, Warsaw was reduced to ruins and destined to live four decades under the communist rule (Figure 3).

It must not skip the reader’s mind that this history of betrayal is deeply rooted in the Polish conscience. History was a cruel teacher. This sense of betrayal culminated at the beginning of World War II when France and the United Kingdom failed to honor their commitment to Poland, which collapsed in less than a week with no nation capable of helping the doomed state. Poland collapsed too quickly, too often throughout its modern history.

Georges Friedman, the leading expert on geopolitical intelligence, once said: “Poland is neither the master of its fate nor the captain of its soul”[7]. Poland succumbed to the wishes of other countries in the matter of its own survival, especially when Germans and Russians joined forces.

As throughout history, it has always been in the core interest of Poland to see the Germans divided, the Austrians worrying about the Ottomans and the Russians weak.

While some historians wrote on how the Poles would not be able to succeed in aiding themselves and others took pride in the certainty of catastrophe, Poland has been helpless for the most part of its history and a victim of occupation and partitioning for centuries.

It is common knowledge for Poles to avoid foreign occupation by all means and retain their independence. This issue primes all others psychologically and practically (whether economically, institutionally and culturally).

In his lengthy description of Poland’s strategy and prerogatives, George Friedman wrote: "Wars take time to wage, and the Poles preferred the romantic gesture to waging war. The Poles used horse cavalry against German armor, an event of great symbolism if not a major military feat. As an act of human greatness, there was magnificence in their resistance. They waged war - even after defeat - as if it were a work of art. It was also an exercise in futility. Listen carefully to Chopin: Courage, art, and futility are intimately related for Poland. The Poles expect to be betrayed, to lose, and to be beaten. Their pride was in their ability to retain their humanity in the face of catastrophe".

As we wrote repeatedly in these pages, Russia and Germany have long been the major issues for Poles. Even though they are less worrisome about the Germans, they’re still suspicious, especially, as history has revealed, that the Germans view the western part of Poland as a part of Germany inhabited by the Poles. They see the potential for a Russian move against the Baltic states and are deeply concerned about NATO’s military weakness.

In their view, should the Russians decide to move decisively, only the Americans would be in a position to bring significant force to counter the attack, and that force would take months to arrive. It is not that they are expecting an attack. But if an attack happens, it will most likely take place in the Baltic, and the Poles will bear the major burden of resistance. The Poles have made substantial efforts in building a military, but they will be unable to hold back the Russians alone. Given the Europeans’ weakness and United States’ distance from the region, they feel isolated[8] .

The Russians have no intention (openly at least) to recreate the Russian empire. Although its president Vladimir Putin said that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a great catastrophe.

Kremlin’s Russia wanted to have a control over Ukraine and Belarus – but much less than imagined – so they can create a buffer and bring them under Russian satellites. The Germans relinquished their expansionist strategy and replaced it with an economic model that ensures their wealthy livelihood. As for the old Austro-Hungarian threat, that has dissolved in a blend of weak nations, none of which can threaten Poland.

Accordingly, the Polish population, in general, agrees that the dangers of life on the North European Plain have been eliminated.

Russians may be weak militarily compared to the United States but not compared to Europe. They want to limit Ukraine and Belarus options in foreign policy because strategically, they are Russia’s first buffer against any attack. The Russians will permit all sorts of internal upheaval to secure that the governments in their orbit will retain their allegiance to Moscow. The Ukraine crisis in 2015 - and the standoff it caused between Russia and the West - is a powerful indicator about the seriousness of Russians when they are threatened by their sphere of influence.

This crisis caused NATO to increase its military buildup in the region through what came to be considered the largest NATO deployment since the Cold War.

This problem has urged the United States to show a more significant commitment to the region. In fact, with the help of the United States and, optionally, the rest of Europe, the Eastern European countries are capable of protecting themselves both militarily and politically against Russian influence. This help could be enhanced if the rest of eastern European countries decide to cooperate with the United States and Europe. But the Poles and Hungarians have little trust in NATO, and they are under constant attack from the EU because of the political elected governments, which the EU disapproves of.

It is essential to note that the United States, after its latest experience in the Islamic world, is moving toward a more distant, balance-of-power approach to the world. This does not mean that the United States is indifferent to what happens in northern Europe. The growth of Russian power and potential Russian expansionism would upset the European balance of power, which is not to Washington's interest. It is useful to quote Thucydides who wrote of the Peloponnesian War: "What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta".

As the United States matures as a global power, it will allow the regional balance of power to stabilize naturally rather than intervene if the threat appears manageable[9] .

A major issue has to be addressed here: the question of German and Russian cooperation as there is a sort of synergy created between the two: on one side we have the German dependence on Russian energy and on the other, the Russian requirement for technology. This relationship is seen with great deal of wariness among the Poles.

According to George Friedman: "the German questions about the future of the European Union have taken them on a more independent and exploratory course. For their part, the Russians have achieved the essentials of a geopolitical recovery. Compared to 10 years ago, Putin has taken Russia on an extraordinary recovery. Russia is now interested in splitting Europe from the United States, and particularly from Germany. As Germany is looking for a new foundation for its foreign policy, the Russians are looking to partner with Europe".

It is hard to believe that this sort of a German-Russian understanding does not concern the Poles. George Friedman goes on to say: "For Poland, the specter of a German-Russian entente is a historical nightmare. The last time this happened, in 1939, Poland was torn apart and lost its sovereignty for 50 years. There is hardly a family in Poland who can't name their dead from that time. Of course, it is said that this time it would be different, that the Germans are no longer what they were and neither are the Russians. But geopolitics teaches that subjective inclinations do not erase historical patterns. Whatever the Poles think and say, they must be nervous although they are not admitting it. Admitting fear of Germany and Russia would be to admit distrust, and distrust is not permitted in modern Europe. Still, the Poles know history, and it will be good to see what they have to say, or at least how they say it. And it is of the greatest importance to hear what they say, and don't say, about the United States under these circumstances".

The Poles today want to escape their history. They want to move beyond history’s tragic sense, and they want to avoid fantastic dreams of greatness. The former did nothing to protect their families from the Nazis and Communists. The latter is simply irrelevant. In the line of history, Poland, as a nation, was powerful for a while when there was no Germany or Russia.

It can adopt a strategy of an alignment with Germany keeping in mind Russia’s weakness and lack of a clear intention of aggression. The rationale explaining it is fairly simple: It is well known to the Poles that both Russians and Germans can change the polish political regime in a heartbeat. In politics, gambling walks hand in hand with total elimination and history is full of examples of forgotten states and civilizations.

For that, a more reliable strategy can be built on a bilateral relationship with the United States. This strategy will lay out a clear understanding that the United States is relying on the balance of power in the region and does not have any intention in direct intervention except when there is no better alternative. This implies that it is up to the Poles to maintain this delicate balance of power in order to gain crucial time to allow the United States to intervene.

But the United States can only secure the western front of Poland. To secure its eastern one, the Poles will be inclined to build their own power, which will cost them a great deal of money- money hard to spend when the threat might never materialize.

However, it is already known in the region that the EU is becoming weaker and Russia’s economy (and to a certain degree its military) power is in decline, despite its last showdown in Ukraine. Eastern Europe countries have lost confidence that Western Europe countries will take risks on their behalf. They worry about Russia, but not quite as much as before.

It is worthy to note that the United States won’t permit to have Europe be dominated by one power (the American fear should not be China or North Korea or ISIS but the amalgamation of the European Peninsula's technology with Russia's natural resources as this would create a power that could challenge American primacy in an arena of great geopolitical and ethnic significance to the U.S.)

Having dealt with the past – history – and settled with the constant – geography – it’s time to approach the future and the potential of Poland’s metamorphosis into a well defined (maybe assertive) state.

3- The hope of the future

It is important to recognize the phenomenal emergence of Poland from the ashes of its traumatic past.

Over the last 25 years, Poland - after centuries of war and defeat has enjoyed peace, stable and vibrant economy, and integration with the rest of Europe.

This nation has seen its luck changing since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. It has witnessed aggressive market economic reform and as a result, the Polish economy grew rapidly for the past two decades (at a rate of more than 4% per year – one of the fastest economic growths in Europe).

Poland nowadays is the sixth-largest economy in the EU garnering massive investment in its infrastructure and companies and the standards of living more than doubled between 1989 and 2012, reaching 62% of the level of the prosperous countries at the core of Europe[10] .

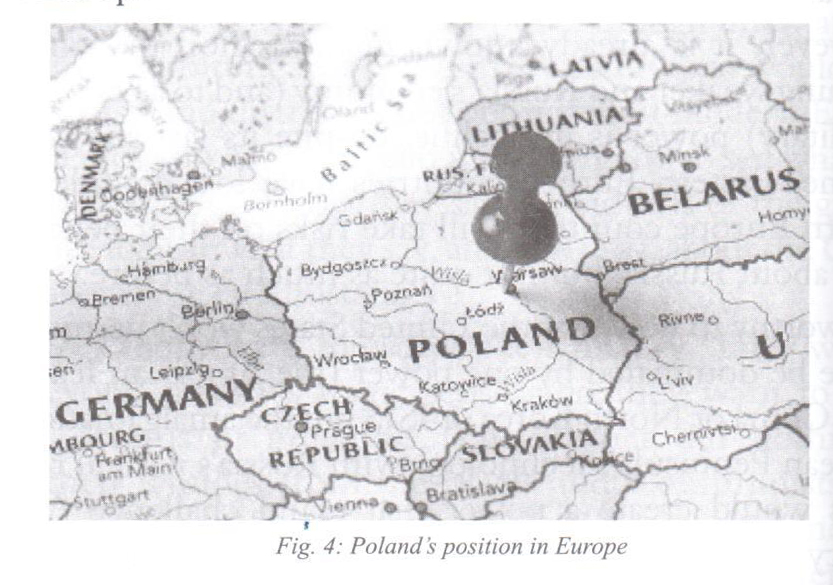

With the creation of the European Union, Poland, like the rest of central Europe, saw it as a solution to its strategic problem. As EU member, the Polish-German problem is solved having the two countries linked through a vast institutional structure (Figure 4).

So to note, Poland willingly entered the European Union for two reasons. First, after experiencing fascism and communism, one of its priorities was to develop a political culture that would render it immune from the contagion. Furthermore, Europe had freed itself from fascism and guaranteed this freedom in an institutionalized form in the EU. The bloc would protect Poland, or so it thought. And second, the entry barrier to EU markets is low, so Warsaw could enjoy the benefits without giving up its nation self-determination and remain sovereign.

Poland has taken advantage of the European Union and along that has witnessed a great deal of political stability.

This stability triggered the long path for the economic development of Poland. So, thirteen years after joining the European Union, Poland is doing well economically. The Polish economy is the only one in the EU to have achieved constant growth despite the economic crisis and it is clearly the economic leader among the former Soviet satellites [11].

But the velvet wedding with the EU is starting to witness troubles. After 2008, Europe began to grasp the feeling of nationalism with several right-wing governments ascending to power.

Eastern Europe started this movement first by electing Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and then electing a similar government in Poland a few months later represented by Bronisław Komorowski, the candidate of Civic Platform. This created a tension between these countries and the EU. Contrary to the United Kingdom, which succeeded to pull away from the European Union, Poland and other Eastern European countries were pushed away.

Poland elected its government through fair elections, mostly free of fraud and no one challenged the elections’ legitimacy. However, the EU had several issues with the policies of the new elected Polish government on a range of changes concerning the judiciary and the media as Mitchell Ornstein, the professor of Political Science at Harvard University, highlighted through his writings in the Foreign Affairs publication: “The voters knew and wanted what they were voting for”.

The newly elected government was of a right-wing inclination. It opposed the policies and institutional positions of the previous, left-of-center government and appointed its followers in all the state institutions, such as courts and media. The new government saw that as a direct act of hostility toward its policies and sought to change the management of the state-owned media and “reform” (in its terms) the judiciary [12].

The EU community perceived these actions as a direct attack on democracy for it directly affected the judiciary body and a lot of hostility voices have been heard in Brussels alleys especially from Germany, which included threats to suspend Poland from participation in some EU functions.

The Polish government’s crisis vis-à-vis the European Union is not really about its reform of the judiciary or media. Rather, it is about Poland deviating from the EU’s ideology. The government opposition of unlimited Muslims immigration is a clear example. Another example is the issue of secularism with Poland being a Catholic country with Catholicism deeply embedded in the Polish conscience. This religiosity contradicts the spirit upon which the EU was conceptualized.

Principally, the most important thing countries like Poland hoped to gain from joining the EU were immunization against fascism. Now, they collided with the EU’s attempt to protect its general ideology. From the EU’s perspective, what the Poles were doing went beyond the pale of acceptable liberal democratic behavior. From the standpoint of Poland, it had adhered to the heart of liberal democratic behavior: its government had won free elections. In challenging the right of an elected government to chart its course, it was the EU that was violating liberal democratic values[13].

The argument here is that just as the British periphery is fragmenting, the Eastern European periphery is also fragmenting. Some regimes are now pulling away from the EU; others are drawing closer. This fragmentation has critical geopolitical consequences in the short term. As the EU alienates Poland and Hungary, further fragmentation will take place as these two countries try to find a balance between Europe and Russia, rather than simply being committed to the center, particularly Germany.

Today, Russia’s push of Poland to the arms of the West is seen as a strategic error. Its direct effect was moving Poland directly into Germany’s sphere of influence. Since Germany accepted this situation by signing a peace treaty with Poland in 1990, it has sought to draw Poland closer and Warsaw has proved to be a willing partner.

The depth of Poland’s relationship with Europe’s leading economy – Germany – is a major reason why it is such a good place to invest today.

This bond is beneficial for both countries. Poland offers Germany a friendly business climate, plenty of skilled labor, and, above all, proximity[14]. A large part of the German export machine is now based in Poland. Poland gets German investment and markets for its goods and Germany profits from the opportunity to use Poland as a low-cost, high-quality production platform to compete with East Asia. Indeed, some German industries are able to produce goods in Poland for less than what they would cost to make in China.

Poland exports soared (46% of its GDP) for being part of the German supply chain – it’s being acknowledged as a great exporting economy. And a recent Morgan Stanley report estimated that 30% to 40% of Poland’s exports to Germany now end up as German exports to the rest of the world. This interdependence explains why Germany is by far Poland’s largest trade partner, buying or selling 25% of Poland’s exports and imports, which total about 12% of the overall Polish economy[15].

This economic booming could not have happened if the German-Polish relationship has not been embedded in the broader European Union. Since Poland joined in 2004, the EU has been so beneficial as well as for the rest of Eastern Europe like securing democratic freedoms and administrative reforms and helping the region liberalize its markets.

In the last decade, the EU has invested more than 40 billion Euros in Polish infrastructure, from building state-of-the-art highways, renovating its decrepit train stations and train lines, cleaning up its rivers and setting up broadband infrastructure.

For Poland to attain the status as one of the world’s most advanced economies, it has to grow at a significantly faster rate. Since it is regarded as a developed economy, such growth will only be achieved through a major multi-sector transformation program with a focus on four strategic elements[16] :

1) Overcoming growth barriers, focusing on mining, energy sectors, and agriculture;

2) Expanding high-potential sectors, focusing on advanced business services, process manufacturing, and food processing;

3) Achieving cost-effective acceleration in technology, focusing on advanced manufacturing and pharmaceutical industry;

4) Halting the demographic squeeze.

The exceptional growth of the Polish economy over the past three decades has brought Poland to a developmental threshold as was shown in a McKinsey Institute study called “Poland 2025”.

This study stated that the country faces a choice for the next decade: to accept a business-as-usual scenario with limited growth, or adopt an aspirational scenario with enhancing its growth ratio.

Choosing one over the other would lead to vastly different outcomes. By taking the first path, the country would remain a regionally focused middle-income economy. By taking the second, Poland would become a main growth engine of Europe, competing successfully in a global market; the country would also experience major improvements in living standards, reaching levels of countries such as Spain, Slovenia, or even Italy in terms

of GDP per capita - The country’s economic success so far has given the society the appetite to expend the effort needed to reach higher levels of prosperity.

To achieve this trajectory, according to the same study, however, important changes and investments are required:

1) Thinking seriously about producing high-tech and knowledge to intensify exports.

2) Focusing on increasing the percentage of research and development, now standing at a poor 0.7% of the GDP.

3) Not depending on foreign investments and not relying heavily on foreign trade.

4) Being wary of the presence of other low-wage countries in its neighborhood that could challenge its status.

Mitchell Orenstein said: “the greatest long-term risk to Poland is that its consumption and wages will rise too fast, crowding out domestic investment and deterring foreign business. In managing their country’s rise, Polish politicians will see themselves walking a fine line between satisfying voters’ concerns and maintaining the country’s cheap labor costs. This dilemma of dependence also explains why Poland is unlikely to join the Eurozone, at least not anytime soon”[17].

None of the goals set in the aspirational scenario in Poland 2025 are unrealistic, but to achieve them, Poland will need a concerted nationwide improvement effort, with the joint participation of the key stakeholders: business, government, and academia. The challenges are many, but so are the country’s strengths, deriving from its large and educated population, its geographic location, and its enviable macroeconomic stability. By designing a plan to grow according to these strengths, Poland is poised to become, in the next decade, one of Europe’s strongest engines of growth as well as a dynamic force in the global marketplace.

The EU is attempting to consolidate prosperity and peace. The prosperity has not achieved its goal yet and if peace fails, Poland will find itself on the brink of a geopolitical reality transferring it back to its doomed history.

Conclusion

In his impressive book “The Next 100 Years”, George Friedman predicted that in the next five decades, Poland would emerge as a regional superpower. Its ascendance will be due to internal factors as well as external ones. These factors have been detailed in these pages.

Warsaw is sometimes referred to as “the Phoenix city”. After all the calamities of World War II, it managed to rise from the ashes like the mythical bird. Today, many observers including ordinary Poles and investors are speculating about the potential of this Phoenix.

Polish officials and the Polish public understand that they are safe for the moment but the future is unknown as Poland is a bustling European country, full of joint ventures and hedge funds[18].

This nation witnessed an amazing transformation in the past quarter of a century. In fact, most speculators think that the country’s best days are ahead of it. It has a well-educated population bestowed with the gift of being entrepreneurial and more Europe-minded than many western Europeans. These factors, and the resilience of its economy, mean that Poland offers huge opportunities in agriculture, construction, and other sectors, and is a fast-growing location for shared services.

Poland’s strategy should come from its understanding that it’s caught up between Germany and Russia. Any entente between these two can deteriorate Poland. To prevent this scenario, Poland is advised to develop a quadri-dimensional strategy.

First, it needs to invest in a national defense strategy designed to make it more costly to the aggressor to attack Poland and create a deeper economic and military relationship with Germany or/and Russia to secure its interest.

Second, Poland by itself is fragile. It must be part of a greater body of alliances. The Intermarium, stretching from Finland to Turkey would be of a sufficient weight and free from the entangled politics of the NATO. NATO was the alliance of the Cold War and the Cold War is long gone. This alliance lives on like a poorly fed ghost administered by a well-fed bureaucracy.

Third, it is of a foremost importance that the Poles maintain their relationship with the global hegemon. Certainly, their reliance on France and Britain in World War II didn’t bring the effect they wanted as they were left alone to their destiny. But their relationship with the United States has had its fair share during different administrations to prevent a German-Russian entente or domination of Europe by one power whether Germany, Russia or a combination of the two (wars have been fought to prevent geopolitical domination by a German-Russian entente as this would threaten the United States interests profoundly e.g. World War I, World War II and the Cold War).

And last, this country must focus on its internal economic development and implement the highlighted four strategies in harmony, as they are essential to Poland’s existence.

It is well known that strategy implementation needs money so relying on others’ donations cannot be guaranteed all the time.

Poland, by building-up resistance – economically and militarily (through alliances) - against Russia primarily in its neighborhood and managing its own fears, will be behaving more like a rising regional power in Central Europe.

Book References:

1- Foreign Affairs Strategy, Terry Deibel, Cambridge, 2007.

2- Geopolitiques: Manuel Pratique, Patrice Gourdin et Yves Lacoste, Choiseul, 2010.

3- Makers of Modern Strategy, Peter Paret and Gordon A. Craig, Princeton University Press, 1986.

4- Poland 2025, WojciechBogdan, Daniel Boniecki, Eric Labaye, Tomasz Marciniak, Marcin Nowacki, McKinsey and Company, January 2015.

5- Strategy and Geopolitics, Mike Rosenberg, Emerald Publishing, 2017.

6- Strategy, Lawrence Friedman, Oxford Univesity Press, 2013.

7- The Next 100 years, George Friedman, Anchor books, 2009.

8- The Next Decade, George Friedman, Doubleday Books, 2011.

9- World Order, Henry Kissinger, Penguin Books, 2015.

[1]- Francis Sempa, Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century, Transaction Publishers, 2002, p.5.

[2]- Sir Halford John MacKinder PC was an English geographer and one of the founding fathers of geopolitics.

[3]- Antonia Colibasanu, Poland Takes on Russia, Geopolitical Futures, February 2017.

[4]- George Friedman, NATO the Middle East and Eastern Europe, Geopolitical Futures, February, 2017.

[5]- The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between the new Bolshevik government of Soviet Union and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's participation in World War I.

[6]- George Friedman, Geopolitical Journey: Borderlands, Stratfor, 2010.

[7]- George Friedman, Geopolitical Journey: Poland, Stratfor, 2010.

[8]- George Friedman, Journey’s End: Warsaw and Budapest, Geopolitical Futures, 2017.

[9]- George Friedman, Poland’s Strategy, Stratfor, 2012

[10]- Mitchell A. Ornstein, Six Markets to Watch: Poland, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2014.

[11]- Christopher Alessi, Poland’s Economic Model, Counsel on Foreign Relations, November 2012.

[12]- George Friedman, Poland Challenges the European Identity, Geopolitical Futures, September 2017.

[13]- George Friedman, Notes from Europe’s Periphery, Geopolitical Futures, March 2017.

[14]- Mitchell A. Ornstein, Six Markets to Watch: Poland, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2014.

[15]- ibid

[16]- Wojciech Bogdan, Daniel Boniecki, Eric Labaye, Tomasz Marciniak, Marcin Nowacki, Poland 2025, McKinsey and Company , January 2015.

[17]- Mitchell A. Orenstein, Poland: From Tragedy to Triumph, Foreign Affairs Magazine, January/February 2014 Issue

[18]- George Friedman, Geopolitical Journey: Poland, Stratfor, 2010.

الجيوسياسية البولندية: قوّة التغيير الإقليمية

إنّ الجغرافيا السياسية تتعلّق بالمنظور والتفاعل بين الدول والإمبراطوريات في بيئة جغرافية معينة. إنّه تأثير الجغرافيا على السياسة. فهو محاولة التمييز، من خلال عدسة السلطة والجغرافيا، بين المعطيات الدائمة، والعابرة.

لكن الأسئلة التي تُطرح عديدة: كيف يؤثر الفضاء الجغرافي على صياغة أهداف ومصالح اللّاعبين الدوليين وما هي أسباب ازدهار وزوال الدول؟ ولمعالجة هذا الموضوع بمقاربة استراتيجية، سنناقش مسألة بولندا.

فهل ستكون بولندا قوّة عظمى إقليمية أم ستكون رهينة لجغرافيتها باعتبارها أرضًا للحرب؟

ولذلك سنأخذ العوامل التالية في الاعتبار: الموقع الجغرافي، تاريخ بولندا بين المأساة والعظمة المتجذّرة في ثقافتها واقتصادها الذي يمكن أن يكون محرّك النمو الجديد في أوروبا.

على مرّ التاريخ، كانت الجغرافيا هي المرحلة التي تصطدم بها الأمم والإمبراطوريات. فجغرافية الدولة تفتح لها آفاقًا في بعض الأحيان وتفرض عليها قيودًا في أحيانٍ أخرى كما هي الحال في بولندا.

إنّ التاريخ البولندي لم يكن دائمًا صورة لمسيرة فشل وانكسار بل كانت بولندا واحدة من أعظم القوى في أوروبا. ففي القرن السابع عشر شُكل الكومنولث البولندي - اللتواني قبل ظهور الإمبراطورية الروسية. هذا التحالف شمل المنطقة بأكملها من بحر البلطيق إلى البحر الأسود تقريبًا، من غربي أوكرانيا إلى مناطق في عمق الدولة الألمانية اليوم.

وبحلول العام 1795، توقّفت عن الوجود كبلد مستقل، وأضحت مقسّمة بين ثلاث قوى ناشئة هي بروسيا وروسيا والنمسا.

ولم تستعد استقلالها إلا بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى، فأمضت بضع سنوات كديمقراطية قبل أن تثبت أنّها غير قابلة للحكم وتستسلم للدكتاتورية. وفي بداية الحرب العالمية الثانية في عام 1939، تعرّضت بولندا للغزو مرة أخرى وقسمت على ألمانيا النازية والاتحاد السوفياتي وعلى مدى السنوات الست القادمة، وجدت بولندا نفسها في وسط ساحات القتال الأوروبية.

وقد شهدت هذه الأمة تغيّرًا في حظها منذ انهيار الاتحاد السوفياتي في العام 1989. فقد شهدت إصلاحًا اقتصاديًا ونتيجة لذلك، نما الاقتصاد البولندي بسرعة على مدى العقدين الماضيين ليكون من الأسرع في أوروبا.

تعدّ بولندا في الوقت الحاضر سادس أكبر اقتصاد في الاتحاد الأوروبي وعليها بذلك أن تتابع سياسة الانفتاح الاقتصادي وضمان أمنها بتقوية قدرتها العسكرية عبر التحالفات الاستراتيجية لكي تسنح لها الفرصة أن تكون قوة إقليمية صاعدة في أوروبا.