- En

- Fr

- عربي

Potential Conflict between Lebanon and Israel over Oil and Gas Resources – A Lebanese Perspective

1. INTRODUCTION

“Let me tell you something that we Israelis have against Moses. He took us forty years through the desert in order to bring us to the one spot in the Middle East that has no oil.”1

This famous comment was made by Golda Meir, former prime minister of Israel, and for many years it held a lot of truth. The lack of oil and natural gas was seen by many observers as one of the main reasons that has driven Israel to become one of the world’s leaders in advanced technology.

But with the recent discoveries of huge gas reservoirs off the coast of Haifa, Israel has the potential of soon becoming an energy-independent country with even a capability of becoming energy exporters.

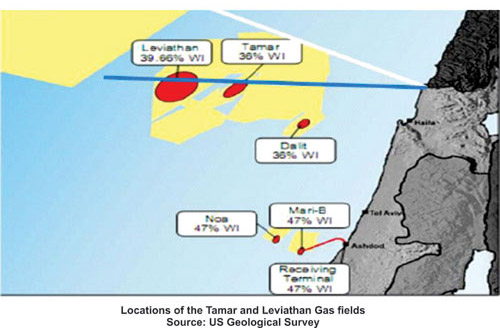

In January 2009, the Israeli oil company Delek with the US Noble Energy company discovered some fifty-five miles off the coast of Haifa the first large natural gas reservoir known as Tamar with an estimated quantity of over 8 trillion cubic feet of gas.2

Early in 2010, another offshore gas field called Leviathan, with a potential of 16 trillion cubic feet – or double that of the Tamar site, was discovered. Once exploited, these two fields could provide Israel with more than its domestic demand and turn Israel into a major exporter of natural gas. The Lebanese were quick to react to the Israeli discoveries, claiming that the two fields were within Lebanon's maritime economic zone.

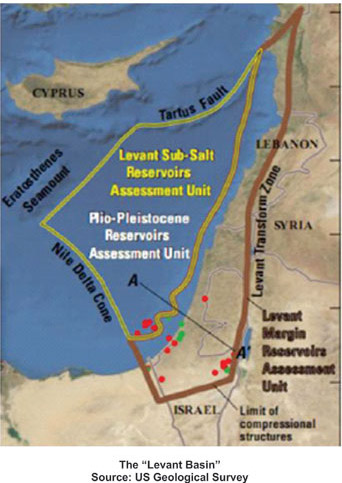

A US survey study published in 2009 claimed that there were 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas in the area off the coasts of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Gaza. In addition the survey indicated the presence of 1.7 billion cubic meters of oil in this area known as the Levant Basin Province.3

Lebanese politicians, awakened by the news, made a series of provocative statements and Hezbollah issued a statement pledging to defend Lebanon's natural resources. Israel responded in kind with the country's infrastructure minister Uzi Landau stating that the IDF would not hesitate to defend the gas fields. As a matter of fact, the Israeli navy was quick to extend a line of buoys two miles into the sea off the Israeli-Lebanese border.4

The purpose of this paper is to gather all the data related to the energy wealth in the Eastern Mediterranean and to review the controversial positions among the various nations involved. Hopefully, sound answers to several important questions will be determined. What can Lebanon do to protect its interests? How can the maritime boundaries be determined and delineated under the present situation? What can the United Nations do to avoid a new dispute? What are the different scenarios for cooperation or conflict to resolve the issue? What role can Hezbollah play to strengthen the Lebanese government’s position to protect the national rights? What are the economic impacts on the economies of Lebanon and Israel and the prospect of both countries becoming energy exporters?

2. PROTECTION OF LEBANESE INTERESTS

When Israel first announced the gas discoveries at the Tamar and Leviathan fields, Lebanese officials claimed that the two sites were located in the Lebanese economic zone and that Israel is attempting to steal Lebanon’s resources. Israeli officials warned that any attempt by the Lebanese state or by Hezbollah to strike at the off-shore facilities would elicit strong Israeli retaliation. Nevertheless, in the Lebanese dossier submitted to the UN concerning delineating the maritime boundaries with Israel, there was no claim of Lebanese ownership of the two areas where Israel had already discovered gas. However, there was evident hope that Lebanon will have the rights to explore for gas and oil in the extreme southern limits of its economic zone close to the Tamar and Leviathan fields.

After several months of political bickering, Lebanon’s parliament endorsed on Thursday, August 4, 2011, a draft law demarcating the country’s maritime borders with Israel and Cyprus. The move which Prime Minister Najib Mikati qualified as a “great achievement” came amid the continuing dispute between Lebanon and Israel over delineating the exclusive economic zones of the two countries.5

Earlier last month, the Israeli government unilaterally proposed Israel’s maritime boundary with Lebanon which Lebanese authorities, as well as Hezbollah, argue infringe on Lebanon’s economic zone by 850 square kilometers.

The drafted law was endorsed by most of the Lebanese parliamentary blocs after introducing an amendment to article six as proposed by PM Mikati. The said article specifies the borders of Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone. Mikati stated, “We discussed this matter with international legal experts…a company specializing in topographic matters will determine the coordinates of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), adding that the EEZ coordinates would be approved later on in a decree stipulated by the Cabinet of Ministers.”6

In his turn, President Michel Sleiman said on August 4, 2011 that the journey towards exploiting Lebanon’s offshore gas and oil reserves had begun. Sleiman expressed hopes that Lebanon’s gas and oil wealth would reduce the country’s public debt if properly managed.

The President warned that Lebanon would stand firm against any attempt to steal its resources: “We will not allow anyone to lay his hand on our wealth which our children and grandchildren deserve. We will not only pass debts to them but also a wealth that will guarantee them a better future so that they remain in Lebanon.”7

In August 2010, the Lebanese Parliament approved a long-awaited draft bill on gas and oil exploration. Lebanon also has pursued its efforts to reach arrangements with neighboring Syria and Cyprus to delineate their respective maritime exclusive economic zones. As a matter of fact, Lebanon reached an agreement with Cyprus, but the agreement has not been ratified yet by Lebanon, fearing that the Turkish part of Cyprus may express its reservation on the agreement and that ratification could jeopardize the economic interest between Turkey and Lebanon.

The Lebanese authorities have asked the UN to help in marking a temporary sea boundary between Lebanon and Israel, a maritime line equivalent of the Blue Line established by the UN in 2000. The UN was reluctant to assume such a potentially thankless task. The demarcation of the Blue Line demanded eleven years of negotiation and hard work in an environment of mutual distrust between Lebanon and Israel. The UN felt that without good will from both sides, the delineation of the maritime boundary could be even more difficult to define.

In the absence of UN assistance, the potential energy wealth of the Israeli and Lebanese coastline could turn the eastern Mediterranean into a potential, new war theater between Israel and Hezbollah. Some reports are circulating that Hezbollah has a unit trained in underwater sabotage and amphibious warfare, an indication of plans to prepare for maritime warfare. Last year, Hezbollah's General Secretary, Hassan Nasrallah, warned that his organization now possesses the capabilities to target shipping along the entire Israeli coastline.

The Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, described the off-shore gas fields as “a strategic objective that Israel's enemies will try to undermine" and vowed that Israel would protect its natural resources. The Israeli navy has presented the government a maritime security plan to defend the gas fields with an estimated cost ranging between forty and seventy million dollars.8

3. THORNY MARITIME BOUNDARIES

In the year 2000, the UN meticulously traced the Israel/ Lebanon Blue Line after Israel withdrew from Southern Lebanon. At the time, the UNIFIL did not establish a maritime boundary between Lebanon and Israel and no one seemed to mind. Lebanon has made no hydrocarbon explorations in the past, but it is eager right now to defend its rights in the gas fields Israel has started to explore near Lebanon’s maritime boundaries.

Both Israel and Lebanon have trillions of cubic feet of underwater natural gas and can benefit tremendously from these resources. However, the problem remains that they need the UN assistance to facilitate an indirect negotiation between them to help demarcating the boundary line. Such a process usually occurs through bilateral negotiation or mutually agreed arbitration; however, such an opportunity is missing because the two states are still in a state of war.

There are several indicators of a potential crisis: first, a promise by Hassan Nasrallah, the General Secretary of Hezbollah, that if Israel threatens Lebanese plans to exploit its oil and gas reserves, the Resistance would force Israel and the world to respect Lebanon's right; second, the subsequent interception by Israelis of major weapons shipments to include six C-704's (anti-ship) missiles; and, third, the recent visit of two Iranian navy vessels to the Eastern Mediterranean. Such activities, from the Israeli point of view, could result in a possible threat to Israeli gas exploration.

Dr. ManouchehrTakin, a senior petroleum analyst at the Center for Global Energies Studies, referring to the Israeli discovery said, “This is a very large discovery which extends into Lebanese waters.” He added, “They could do it jointly through what is called unitization, and have outside oil companies evaluate the total resource and estimate how many cubic feet are on the Israeli side and how many cubic feet are on the Lebanese side. Then the reservoir could be developed jointly with the profits shared according to each side’s relative portion, but they’d have to agree and be in a good cooperative mood.”9

Asked what would happen if Israel and Lebanon do not enter a good cooperative mood in the near future, Dr. Takin said, “One side can drill for itself, the other side can drill for itself and have a race. In the end, this will be damaging because if you produce too rapidly you end up not producing as you would otherwise.”10

So far the Israeli and Lebanese sides have dealt with the issue with militaristic oratory and bravado without showing any will to find the right advice on how to solve the challenge between them. Lebanese Energy Minister, Jibran Basil said on June 17, 2010, that his country “…will not allow Israel or any company working for Israeli interests to take any amount of our gas that is falling in our zone.” He said, “Noble Energy was warned not to work close to Lebanon’s economic zone.” On the Israeli side Minister Uzi Landau replied, “We will not hesitate to use our force to protect, not only the rule of law, but the international maritime law,” insisting that the Lebanese are not only challenging the Israeli findings but the Israeli existence and rights. He added, “These areas are within the economic waters of Israel.”11

A coastal state is entitled to explore for oil and gas in its economic zone, which extends 200 nautical miles according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. A half-way point is used when the distance between countries is less than 400 nautical miles. Haifa in northern Israel is about 148 nautical miles from Cyprus. The Leviathan field lies about 81 miles off Haifa, and Tamar is about 55 nautical miles from the city. Israel has reached an agreement with Cyprus over the maritime boundaries between the two countries. There is no dispute between the two countries over Leviathan or Tamar. We cannot extrapolate on the agreement reached with Cyprus when we learn that the Lebanese coastal border town Naqoura is located at only 23 nautical miles from Haifa. Lebanon, consequently, does not recognize the Israeli line of maritime boundary which was drawn as a perpendicular straight line to the borderline of Naqoura. The rules to delineate boundaries are well known internationally and these lines, in most cases, are not straight lines. However, the Israelis are not signatories of the International Maritime Convention and Law and are not, in this case, abiding by the legal norms which would help to solve such a thorny issue concerning the maritime boundaries.

There are more complicated matters emanating from not only Beirut but also from Cairo. First, Beirut brokered a maritime agreement with Cyprus, but the Lebanese Parliament has yet to ratify it. The news about the size of the Leviathan field has also prompted protests from Cairo that warned it would follow closely the drawing of the boundary between Israel and Cyprus to insure it does not infringe on Egypt’s economic zone or on the maritime agreement previously signed with Cyprus.

Turkey has placed, in its turn, additional pressure on Cyprus by declaring the island’s maritime agreement with Israel null and void. Ankara objects to any such agreement being signed until a solution is reached regarding the future of the island. According to one Turkish official’s statement, “Turkish Cypriots also have rights and jurisdiction over maritime areas of Cyprus.”12

In a surprise development, Turkey expressed a strong position vis-à-vis the Cypriot government dealing with the issue of gas and oil in the Mediterranean. The Turkish official position went as far as to threaten taking the necessary steps to counter any Cypriot attempt to start gas exploration in the EEZ. AhmetDavutoglu, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey expressed theTurkish views by saying, “Cyprus has no rights to take any steps towards exploration for gas before an agreement on this matter is reached between the two parts of the island.” He also added, “None of the two parties – Greek or Turkish – had the right to act alone on the matter of the Cyprus national wealth before reaching a final solution for Cyprus.” Additionally, he stated, “All the efforts towards dealing with the exploitation of natural resources should be undertaken by representatives of both the Turkish and Greek communities.” Davutoglu reiterated his government’s strong position on the matter by threatening to take all necessary steps to counter any unilateral actions.13

Along the Palestinian coast of Gaza, another gas field was discovered in 2000. Israel, however, insisted that any gas in this area is an Israeli right pending a full peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Taking into consideration the controversial positions of the various nations involved, one can see the issue of gas and oil in the Levant Basin is a very highly complicated matter politically, legally and strategically. Of course, it remains within each state’s authority to defend its rights within its own exclusive economic zone which should be fixed based on the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Such steps might not be enough to solve the clash of interests among the various states and parties involved and it may require a call for a regional conference sponsored by the United Nations with the main task of making negotiations possible between Lebanon and Israel as well as between the Turks and Greeks in Cyprus. International negotiation and arbitration loom necessary to avoid future military conflict.

4. LEBANON’S APPROACH TO PROTECT ITS RIGHTS

After loud political bravado, Lebanon has started to approach the problem from four different angles– political, legal, technical, and economic.

From the political angle, all the Lebanese political forces have expressed a strong will to cooperate in protecting Lebanon’s gas and oil wealth. The Cabinet of Ministers was quick during the first week of August 2011 to agree on a new draft law to demarcate the EEZ and to immediately send the matter to Parliament to approve the law. The various parties within the opposition have expressed a unanimous vote in support of the new law.14

On the other side of the scale, Hassan Nasrallah, the General Secretary of Hezbollah, came out on two different occasions to explain the steadfastness of the party towards protecting Lebanon’s resources, sending clear messages about the will of Hezbollah to take all necessary steps including the use of force to stop the Israeli attempts to steal Lebanon’s underwater resources.15

The Lebanese government is preparing to undertake several steps towards the UN and towards Cyprus in the near future to counter all the Israeli attempts to confiscate about 450 square miles of Lebanon’s EEZ. The Israelis are using as a basis for their claim the agreement they have reached with Cyprus. The source of the problem comes from the delinquency of the agreement reached between Cyprus and Lebanon in 2007 when the two parties left a line of 17 kilometers in length in the region of point 23 undecided. Israel has taken advantage of this delinquency to confiscate the area along this line.

It was made clear during the contacts between the Lebanese and Cypriot Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the boundaries between the three countries should be agreed on by all three parties and that the Lebanese position denouncing the Israeli confiscation of 850 square kilometers is a valid one.

On the legal level, the parliament has already enacted two new laws to manage all the aspects of the matter from delineating its maritime economic zone to collecting all the data necessary to launch a wide exploration operation in the sea as well as on the ground. Lebanon is deploying intensive effort to solve the actual dispute with Israel and is pressing, consequently, for the UN to help draw a temporary maritime line – similar to the Blue Line that was drawn with the help of UNIFIL between the two countries that began in the year 2000.16

On the technical side, Lebanon is completing all the necessary studies and preparations to select the qualified personnel as well as the management system to launch an exploration effort and to take all necessary steps to build the needed infrastructures according to international standards. Now Lebanon should seek the highest international technical expertise to prepare all the studies to back the file Lebanon has prepared to send to the United Nations.17

On the economic side, there are three areas of preparation: first, the preparation of the information to study the potential investment needed for the exploration and building the infrastructure; second, the preparation and collection of all the required data for the exploitation and marketing of the gas; and, third, the preparation of an economic plan on how to use the revenues to extinguish the national debt that now exceeds fifty-five billion dollars, and the urgency to look for foreign investors and companies to build a consortium for starting the exploration.

5. LEBANON’S REQUEST FOR A MARITIME “BLUE LINE”

For the past three years, the Israeli delegation to the tri-partite meetings (between Lebanese and Israeli delegations sponsored by UNIFIL) have been urging Lebanon to enforce security measures on the sea near the border line, and Lebanon has been saying that it didn’t want to approach the boundary line and risk a confrontation with the Israeli navy. After the discovery of the Tamar and Leviathan fields, the Israelis marked a line with buoys, trying to delineate the boundary based on their own views and interests. Lebanon has refused to accept the unilateral Israeli move.

Lebanon has demanded that the United Nations help in drawing a maritime (temporary) security line similar to the Blue Line drawn between the two countries. The UN authorities declined to get involved in such a highly difficult and complicated task, saying that drawing such a line falls within the responsibility of the two countries. The Lebanese delegation to the tri-partite commission has explained to the UNIFIL authorities that Lebanon is not requesting to draw the legal maritime boundaries between the two countries but requesting an agreement sponsored by the UN on a temporary maritime line based on the same principles which were used to draw the Blue Line. Lebanon took the matter to the UN Security Council by sending a delegation to explain to the permanent members of the Council as well as to the General Secretary the position of Lebanon vis-à-vis the maritime line and proposing a line which was established by Lebanese experts based on international laws as well as on the resolutions of the Lebanese-Israeli Armistice of 194918.

On July 14, 2010, the government took the matter of delineating its exclusive economic zone officially to the United Nations General Secretary in a memorandum delivered through its permanent mission to the United Nations. The memorandum states, “In accordance with Articles 75(1) and 75(2) of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, to which the Republic of Lebanon is party by virtue of its Law number 295 of 22/ 2/ 1994, we hereby deposit with the United Nations Secretary General the charts and lists of geographical coordinates of points defining the Southern limit of Lebanon’s Exclusive Economic Zone.” The Lebanese file contained a report concerning the delineation of the southern limit of Lebanon’s EEZ. The report states that drawing such a line was made in accordance with the following:

- The provisions of the Paulet-Newcombe agreement of 3 February 1922, which entered into force on 10 March 1923, delimiting the southern of Lebanon from Ra’s Naqurah at point 1B, the coordinates of which were officially confirmed on the 1945 map detailing the borders of Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine further to the Armistice agreements among the parties.

- The manual on technical aspects of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982)

The base line of the Southern Lebanese coast was delimited using the following official maps:

- The British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 2634 (Beirut to Gaza, 1:300,000) produced by the UK Hydrographic Office.

- The British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 183 (Ra’s at Tin to Iskenderun, 1:1,100,000) produced by the UK Hydrographic Office.

- Chart B-1 (area of Naqourah, 1:20,000) produced by the office of Geographical Affairs, LAF Command, updated in June 2004 on the basis of aerial photographs taken in 2001/ 2002.19

Using that base line, and with reference to the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea provisions, the southern limits of Lebanon’s EEZ was determined as the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest point on the base line of Lebanon and Israel.

The southern limits of Lebanon’s EEZ drawn on the British Admiralty Nautical Charts with a list of its coordinates were forwarded to the UN (the report and the list of coordinates are contained in Annexes A and B attached to the report).

In the last meeting of the tri-partite committee in March 2011, Lebanon explained the drawing of the maritime line to the UN side and asked UNIFIL to discuss and study the matter with the Israelis. The Israeli side agreed to take a copy of the Lebanese file, and Israel and UNIFIL will be discussing the possibility of launching a negotiation between the Lebanese and Israeli sides looking for an agreed solution.

Lebanon insists that the prepared study is accurate, serious and meets the highest international standards. The international community has expressed its satisfaction about the Lebanese extensive work. The US State Department was encouraged by the steps taken within the tri-partite meeting and dispatched a special envoy (Frederick Hof) to Beirut to discuss with the Lebanese authorities their plan to draw the security temporary line. In the opinion of the American special envoy, the Lebanese study fits the international high standards, and the matter now awaits the Israeli response.

Based on the Lebanese established line, parts of both Leviathan and Tamar reservoirs will be on the Lebanese side of the maritime boundary.

6. HEZBOLLAH’S STRATEGY

Tensions are rising in the Eastern Mediterranean between Lebanon and Israel over roughly 850 square kilometers of contested waters that contain considerable underwater gas reserves. The heated declarations of both sides drive certain analysts to talk about the possibility of a future war that Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, and Israel will be interested in, each for their own reasons.

Both Israel and Hezbollah, in the way they are dealing with the gas discovery seem to be eager to discover another border conflict in addition to the Cheba’a Farms-Kfar Shouba-Ghajjar conflict.

In a televised speech on July 26, 2011, Hassan Nasrallah, the General Secretary of Hezbollah, addressed in details the different parameters of gas and oil issues in the Mediterranean, focusing on the following:

- All that is underwater gas in Lebanon’s EEZ should be considered as national wealth that will bring revenues of several hundred billion dollars.

- He called on the Lebanese government as well on the people of Lebanon to seize this great opportunity and to act with great responsibility to preserve the national wealth.

- He urged the Lebanese Parliament to quickly approve the Energy Law while the Ministry of Energy starts to put up bolder decrees and plans to exploit the national resources:“The Lebanese government should prepare all the plans to start exploration within 2011.”

- The revenues from the exploitation of these national resources would provide all the funds to solve Lebanon’s financial, economic, and social problems.20

Nasrallah said that Hezbollah will be basing its strategy on what the Lebanese government decides reference the delimiting of its EEZ. He added that Hezbollah has full confidence in the present government of Najib Mikati and called on the government to act swiftly and effectively in taking the necessary steps to start exploration. Nasrallah went on to say that Lebanon is willing and capable of protecting the exploration operations and whatever facilities the companies build in the disputed 850 square kilometers region. Hezbollah considers the defense of this region as a central mission and stands ready to repulse any Israeli aggression. The General Secretary concluded that Lebanon is capable and has all the means of power to defend its rights and national resources.

It seems that the stakes are high for a new border dispute between Lebanon and Israel in which Hezbollah will have the initiative to play a dominant role. Under these new conditions the US government and Israel should fear a flare-up in the Eastern Mediterranean knowing that Hezbollah is armed with Chinese-designed Iranian-made C-802 anti-ship missiles that could be devastating against Israeli offshore gas platforms and installations. Hezbollah also has prepared for such possible scenarios by organizing a sea-borne commando unit.

The new position of Hezbollah raises the possibility of a new border dispute. Under such a possibility, the US government would do better to increase its role in trying to find an exit from the present imbroglio about the maritime boundaries between Lebanon and Israel. By increasing its diplomacy to solve the problem, the US would be standing by the Lebanese government and stopping Hezbollah, Teheran, and Damascus from instigating a new dispute. The Israelis on their side must stand ready to encourage the United Nations to arbitrate the boundary dispute under the Law of the Sea Treaty (1982), to which Israel is not even a party.21

7. COOPERATION OR CONFLICT

The Israeli gas discoveries are stirring the pot of regional turmoil and are provoking different reactions from all the players in the Eastern Mediterranean. It looks as if the region is on the verge of facing a very volatile and highly complicated situation.

Despite Israel’s vast offshore area, most of their gas drilling happens to be at both extremities of their zone. In the north, we see them drilling right on the boundary line with Lebanon, and in the south we see them drilling on the boundary with Gaza. Such a scenario has happened in other regions of the world where petroleum companies drill close to international boundaries. In some cases, there were concerns that such techniques are not used for intimidating the other side but also giving the potential to drill under the neighbor’s border and exploit the other’s oil or gas reserves. Everyone can recall such claims being made between Kuwait and Iraq as well as along the Australian/ Indonesian boundaries in the Timor Sea. With such uncertainty in mind, the Israeli drilling could cause similar concerns to both the Lebanese government and to the authorities in Palestine. The Tamar and Leviathan fields apparently stagger the border with Lebanon, and the reserves should be jointly owned. In the south there is exactly the same situation between Gaza and the adjacent Israeli waters. Such uncertainty about Israeli intentions is totally unacceptable. Oil and gas exploration companies must determine and respect the various parties rights in carrying out such exploration projects, especially in such politically sensitive areas like the Middle East, taking in consideration that such an illegal practice could lead to armed disputes.

The political situation has witnessed more tension after the Israelisand the Cypriots signed an agreement in December 2010 on splitting the 250 kilometers of water that separate them. Turkey objected to the agreement and a Turkish Ministry of Energy official threatened that Ankara was considering starting oil and gas exploration off the northern Turkish-controlled coast of Cyprus.22

The situation developing on the coast of Gaza represents an example of clear violation of Palestinian rights when we see the Israelis pumping gas from their Mari-B well to onshore Israel. The field sits right on the Gaza border. To the west of this field are other explorations known as Noah and Noah South; these reserves do stagger the border line and should be jointly owned. Lebanon may well end up with a similar scenario with the possibility of the gas fields extending into its territory. The present uncertainty about Israeli intentions creates a high-risk environment between Lebanon and Israel. If the Israelis do not come to an agreement with Lebanon, acknowledging its rights and claims based on the real boundary line, there exists a strong possibility for a new war between the two countries.

At the end, with the volatile and complicated developing situation, we can wonder whether the abundant natural gas discoveries are a blessing or a curse for the Eastern Mediterranean countries! The answer to this question will depend on the political wisdom of the various leaders to seek cooperation rather than to promote conflict.23

8. FEASIBILITY, IMPLICATIONS, AND GAINS

Israeli technology in gas operation is several years in advance of all the neighboring countries. The recent finding of theTamar and Leviathan fields near Israel has given Israel the possibility of becoming an energy-independent country. However, Israeli investors are asking why to stop there! They believe that Israel could become one of the world’s leading gas exporters – so much so that it has the chance to flourish economically. At any rate, it is good logic for Israel to continue the operation to create a self-sufficient country in light of new information concerning an Egyptian will to re-negotiate the prices of gas sold to Israel with the intention to double the actual prices.

Other Israeli analysts think that nobody has bothered studying the state of the international market nor have they put any deep thought into how processes in that market could affect the economic feasibility of the whole gas operation. It seems to these analysts that nobody has bothered to look into the future of the gas international market. Investors and the media are all caught up in the emotionally supercharged environment created by the huge gas discoveries. Israel should look at the matter from the angle of much larger gas explorations which will take place in the near future in other areas in the world, especially in the United States, Qatar, and other Middle Eastern supplier countries such as Iran and Iraq.24

Also, in the United States, there are two gigantic on-shore structures containing natural gas. The first one is Marcellus and is estimated to contain between 160 and 500 trillion cubic feet. Besides the gigantic depot, the technology used in horizontal drilling and production technique will create very soon a glut on the international gas market. Another location in the United States is on the Alaskan shore where Shell Oil Company has been acquiring ten-year federal leases. The company has spent more than two billion on the leases and one and a half billion dollars preparing a drilling program with state of the art mitigation and safety measures.25

More attention should be put on “Ras Laffan” – the name of the Qatari city that has a gigantic gas liquefaction terminal. The liquefied gas can be transported by tanker all over the world, from Turkey to South America, India and China.26

A newer regional development could affect the Israeli economic gains. This is the new Iranian, Iraqi, and Syrian agreement to build a pipeline to supply these countries with gas with the possibility of extending the pipeline to other countries.

The gas exporters have not yet formed a cartel. That may be part of the reason why gas prices were fluctuating. In recent years, there have been moves to form a cartel – a sort of OPEC for gas. Ostensibly, a cartel of this sort would benefit major gas producers the world over. But the candidates to be part of such a cartel are Iran, Russia, Qatar, and Algeria – and most of them would oppose Israel becoming a member of such a cartel.

All this argument shows that there are more unknown parameters than known parameters that could negatively influence the potential Israeli gas market. All these uncertainties need to be taken into account by all eastern Mediterranean countries that are willing to invest time and huge financial resources in future drilling operations.

9. CONCLUSIONS

Several scenarios could develop in the near future. The first scenario is that Israel comes to an agreement with Lebanon on the maritime boundary line and recognizes the Lebanese right to a certain percentage of the two wells, Tamar and Leviathan. Based on that agreement, the two countries could cooperate on the way to split the quantities of gas or the revenues in case the wells are given to one company to exploit. Such a solution would be commercially viable, especially if it avoids duplicating plants and pipelines for pumping gas to respective markets. The second scenario is that the two countries do not reach an agreement, and this will open the way to drilling the reserves from both sides, causing great damage to the reservoir. The third scenario is that an international organization or company could establish a plan specifying the share of each country that allows each side to pump its fair share through the method of unitization.

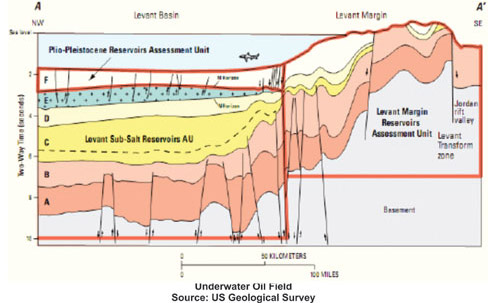

The current offshore situation in the Eastern Mediterranean offers great potential for the discovery of large quantities of oil and gas. The study of the sea bed indicates that beneath the thick, dense layers of salt and beyond the gas reserves there are vast reserves of oil. Drilling for this oil will require larger amounts of money and greater time. What is interesting about the Eastern Mediterranean is that once you have located oil and gas reserves, they have a natural ability to recharge themselves as a result of geological activity.

During the visit of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to Beirut in October 2010, Iran and Lebanon signed a series of economic agreements, including oil and gas exploration accords. However, as Iran is the subject of economic sanctions, particularly its energy industry, these accords are not likely to be realized.

Although animosity between Israel and Hezbollah keeps them constantly on the edge of armed conflict, the very vulnerability of oil rigs to land-based missiles or air strikes would be a major restraining factor for both sides (Israel and Lebanon). Unlike Israel, Lebanon does not have any oil rigs off its coast, but it is clearly in Israel’s interests that Lebanon eventually does make significant underwater finds. It would be clear then that any attack on Israel’s gas facilities would bring the immediate attack on the Lebanese facilities. Without such a deterrent capability, Israeli gas rigs would be at constant risk of being attacked by Hezbollah.

The Lebanese rights, as well as those of the Palestinians, must be protected. The two governments should unite in their efforts to achieve the common goal of preventing the Israelis from seizing their rights. In such an endeavor, Lebanon has a distinct advantage over the Palestinians in what relates to urging the United Nations to be a mediator. If necessary, Lebanon will take the case against Israel to the International Court of Justice.

When exploited, these natural resources will provide Lebanon with a great opportunity to diversify its sources of income and growth, to empower the national economy, and to open way for a sustainable leap into the range of high income countries.

The discovery of gas and oil would help Lebanon to achieve higher energy security and help improving the industrial, transportation and electricity sectors (50% of the electricity generated in Lebanon is from the combined cycle gas turbines).

In fact, the oil and gas discovery will have a very positive effect on the Lebanese public finances and on the economy as a whole. Such effect will benefit not only public sectors like electricity and transportation and increase public revenues but will also help in reducing the cost of all local industrial goods and services.

Endnotes

1 Shining Star, “Could Israel Become Oil Production Leader?,” Ynet News, http:/ / ynetnews.com/ articles/ 0,7340,L-4049471,00/ html

2 Nobel owns 36% of Tamar, while Isramco Negev owns 28.75% and Delek Group has a 31% share. The Tamar site plans on selling gas to Israel in 2013.

3“Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Levant Basin Province, Eastern Mediterranean,” USGS Fact Sheet 2010-3014,http:/ / pubs.usgs.gov/ fr/ 2010-3014/

4 “Landau: Israel Willing to Use Force to Protect Gas Fields,” Ynet News, http:/ / www.ynetnews.com/ articles/ 0,7340,L-3910329.00/ html

5WassimMroueh, “Parliament Endorses Law on Maritime Borders,” The Daily Star, 5 August, 2011.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8 Nicholas Blanford, “The Next Big Lebanon-Israel Flares-up: Gas,” Time, April 6, 2011, http:/ / www.time.com/ time/ world/ article/ 0,8599,2061187,ou.html

9 Dr. Manouchehr Takin, “Natural Gas ‘War’Between Israel and Lebanon Could Lead to a ‘Drill Race’,:http:/ / www.greenprophet.com/ 2010/ 07/ natural-gas-israel-lebanon/

10 Ibid.

11 “Conflict Looms Over Eastern Mediterranean Gas Reserves,” Gulf Times, July 2010, http:/ / www.gulf-times.com/ site/ topics/ article.asp?Ca_no=2&item/

12 “Cyprus and Israel Reach Agreement for Maritime Delimitation,” International Boundaries Research Unit, Durham University, 11 January, 2011, http:/ / www.dur.ac.uk/ ibn/ news/ boundary_news/ ?item

13 “Russia among First Investors in Lebanon’s Oil,” Assafir Newspaper, 6 August, 2011.

14 “Parliament Approves Maritime Borders Law,” Annahar Newspaper, 2 August, 2011.

15 Nasrallah addressed the potential conflict with Israel over the underwater natural resources in two televised speeches broadcasted by Al-Manar Television. The last speech where he outlined the strategy of Hezbollah was broadcast on July 27, 2011at 20:30 hours. See also http:/ / www.assafir.com/ article/ aspx?&Edition ID=1906&channel/

16 “Parliament Endorses Law on Maritime Borders,” The Daily Star, 5 August, 2011:2.

17 “The Israeli Seizure of Resources Is a Priority for the Government, 17 kilometers Are the Central Point,” Annahar Newspaper, 11 July, 2011.

18 The official Lebanese request to delineate a maritime Blue Line was presented in the Tripartite meeting at Naqoura by the representative of Lebanon General A.R. Chehaytly, who traveled to New York later on to present the Lebanese File to the UN General Secretary.

19 The official Lebanese report on the Maritime Delimitation of Lebanon’s Exclusive Economic Zone was presented to the UN by the Permanent mission of Lebanon to the UN on July 14, 2010.

20 The speech was delivered live on Al-Manar Television on July 26, 2011 at 20:30 hours.

21 Ariel Cohen, “Behind the Israeli-Lebanese Gas Row,” Wall Street Journal, 26 July, 2011.

22 David Rosenberg, “Political Tensions Cast Shadow over Eastern Mediterranean Gas Bonanza,” Lebanonwire, 21 December 2010, http:/ / www.lebanonwire.com/ 1104MLN/ 11042209ML_asp/

See also “Cyprus and Israel Reach Agreement” in endnote 12.

23 Alex Joffe, “Fueling Israel’s Future,” opinion/ columnist, Jerusalem Post, http:/ / www.jpost.com/ opinion/ columnists/ article.aspx?id/

24DoronTsur, “Shrinking Leviathan to its natural Size,” Haaretz, http:/ / www.haaretz.com/ misc/ article_print_page/ shrinking_leviathan.../

25 James A. Baker III, “Cut the Red Tape, Already: open Up Drilling in Alaska,”USA Today, 1 June, 2011: 11A.

26 See endnote 24.

Annex “A”

Translated from Arabic

Report concerning the delimitation of the southern limit of Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone

In accordance with the United Nations Convention on the law of the Sea, to which Lebanon acceded by virtue of Law No. 295 of 22 February 1994, and in particular the following articles on the delimitation of exclusive economic zones, the text of which is contained in annex 1:

- Article 5 concerning the normal baseline;

- Article 7 concerning straight baselines;

- Article 14 concerning the combination of methods for determining baselines;

- Article 15 concerning the delimitation of the territorial sea between States with opposite or adjacent coasts;

- Article 16 concerning charts and lists of geographical coordinates;

- Article 55 concerning the specific legal regime of the exclusive economic zone;

- Article 56 concerning the rights, jurisdiction and duties of the coastal State in the exclusive economic zone;

- Article 57 concerning the breadth of the exclusive economic zone;

- Article 58 concerning the rights and duties of other States in the exclusive zone;

- Article 59 concerning the basis for the resolution of conflicts regarding the attribution of rights and jurisdiction in the exclusive economic zone;

- Article 60 concerning artificial islands, installations and structures in the exclusive economic zone;

- Article 63 concerning stocks occurring within the exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal States or both within the exclusive economic zone and in an area beyond and adjacent to it;

- Article 73 concerning the enforcement of laws and regulations of the coastal State;

- Article 74 concerning the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts;

In accordance with the provisions of the Paulet-Newcombe agreement of 3 February 1922, which entered into force on 10 March 1923, delimiting the southern border of Lebanon from Ra’s Naqurah at point 1B, the coordinates of which were officially confirmed on the 1949 map detailing the borders of Lebanon, Syria and Palestine further to the armistice agreements between the concerned parties;

In accordance with the manual of technical aspects of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982);

The baseline of the southern Lebanese coast was delimited using the following available maps:

- Admiralty nautical chart No. 2634 (Beirut to Gaza, 1:300,0000 produced by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office;

- Admiralty nautical chart No. 183 (Ra’s at Tin to Iskenderun, 1:1,100,000) produced by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office;

- Chart B-1 (Area of Naqurah, 1:20,000) produced by the Office of Geographic Affairs, Lebanese Armed Forces Command, updated in June 2004 on the basis of aerial photographs taken in 2001-2002.

Using that baseline, and with reference to the provisions of the United nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the southern limit of Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone was determined as the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest point on the baselines of Lebanon and the neighboring State.

The southern limit of Lebanon exclusive economic zone was then plotted on Admiralty nautical chart No. 183, and a list of its coordinates was compiled.

The above-mentioned chart and list of coordinates are contained in annex 2.

There is a need to conduct a detailed survey, using a global positioning system, of the shore contiguous to the southern limit, including all islands and spurs, with a view to updating the nautical charts and the baseline accordingly in the future.

List of Geographical Coordinates

for the delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone in WGS 84

The following tables contain position information for the Median Line between

Lebanon and Palestine

All positions are referred to WGS 84 joined consecutively by geodesics

Southern Median Line (Lebanon – Palestine)

|

Points |

Degrees |

Minutes |

Seconds |

|

Degrees |

Minutes |

Seconds |

|

|

18 |

35 |

6 |

11.84 |

E |

33 |

5 |

38.94 |

N |

|

19 |

35 |

4 |

46.14 |

E |

33 |

5 |

45.79 |

N |

|

20 |

35 |

2 |

58.12 |

E |

33 |

6 |

34.15 |

N |

|

21 |

35 |

2 |

13.86 |

E |

33 |

6 |

52.73 |

N |

|

22 |

34 |

52 |

57.24 |

E |

33 |

10 |

19.33 |

N |

|

23 |

33 |

46 |

8.78 |

E |

33 |

31 |

51.17 |

N |

الصراع بين لبنان وإسرائيل حول الثروة النفطية دراسة من نظرة لبنانية

يهدف الباحث في دراسته إلى جمع كل المعلومات المتوافرة حول وجود الطاقة والثروات النفطية في البحر المتوسط ومنطقة الشرق الأوسط ومراجعة المواقف المثيرة للجدل بين مختلف الدول المعنية.

يطرح الباحث عدة أسئلة ومنها:

ماذا يفعل لبنان لحماية مصالحه؟

كيف يمكن ترسيم الحدود البحرية في الوضع الحالي؟

ما هو موقف الأمم المتحدة لتجنّب أي نزاع جديد؟

ما هي السيناريوهات المختلفة للتعاون والخلاف لحل الجدال القائم حاليًا؟

ما هو دور حزب الله لتقوية موقف الحكومة اللبنانية لجهة حماية حدوده؟

ما هو الأثر الاقتصادي على الاقتصادين اللبناني والاسرائيلي وإمكانية أن يصبح البلدين مصدرين للنفط؟